Praxis: A Writing Center Journal • Vol. 22, No. 2 (2025)

Tracking Dispositional Development in Tutor Education: An Experiment in Tutor-Led Assessment

Tyler Gardner

Brigham Young University

tyler_gardner@byu.edu

Madilyn Abbe

University of California, Berkeley

madilyn.abbe@gmail.com

Gabbie Schwartz

Brigham Young University

gabriellals6251@gmail.com

Olivia Drew Swasey

University of Wisconsin – Madison

1oliviadrew@gmail.com

Abstract

Building on discussions of liminal threshold concepts and sensemaking in the writing center, this article engages the way tutor training extends beyond skill acquisition to involve dispositional development—specifically exploring how tutor education fosters collaborative dispositions in new tutors. Experimenting with tutor-led assessment, this article provides three tutor-conducted case studies that track the experience of new tutors in their first semester of writing center training and identify key training elements that contribute to dispositional development. While these case studies reveal the development of collaborative dispositions to be a non-linear and subjective process, they highlight the value of metacognitive and interpersonal training activities that help new tutors bridge practical experience with theoretical understanding.

I didn’t know before accepting the job how I would feel invested in students, or that demonstrating empathy with them improves the relationship and their perspective on writing. Overall, tutoring is much more than pulling out a red pen. This job has become much more to me than improving writing. I now feel that the point is connecting with others! – Writing tutor at the end of their initial training

The above epigraph reflects the enthusiasm and focus that a writing tutor can gain from developing a pronounced orientation to who they are and the work they do. Initial tutor education in the writing center is as much about facilitating this orientation as it is about developing specific knowledge and skills. Mike Mattison points to this when discussing his initial hesitancy to leave Stephen North’s essay “The Idea of a Writing Center” off his writing center course syllabus and lose that forceful articulation of what it is we think we are doing in the center (5). In omitting North’s identity-forming polemic that operated for so long as a “special handshake for the initiated” (Boquet & Lerner 171), Mattison recognized the need to “work harder, and more deliberately, to help [tutors] establish a sense of themselves as [tutors]” (5). In Sensemaking for Writing Programs & Writing Centers, Rita Malenczyk et al. draw on sensemaking theory to consider what the “micro interactions of faculty, tutors, and others—show us about attitudes and orientations toward program and center work” (1). In that same vein, this article explores how tutors develop a sense of themselves, specifically the kind of collaborative disposition displayed in the epigraph above.

Descending from John Dewey’s work on habits of mind, dispositions have become a staple of teacher development discourse, while remaining difficult to define and even harder to assess (Choi; Rike; Wayda). While not using the language of dispositions, discussions of peer tutor training have long engaged the realm of dispositions in terms of considering “cognitive and affective attributes that filter one's knowledge, skills, and beliefs and impact the action one takes in classroom or professional settings” (Thornton 62). In framing peer tutoring as “the systematic application of collaborative principles” (334), Kenneth Bruffee made the case for deliberate tutor training “based on collaborative learning” as opposed to “merely selecting good students and giving them little to no guidance, throwing them together with their peers” (334). Advocating for tutors to be trained in collaboration, Bruffee saw the peer tutor role as practicing “a set of behaviors” (Holt 102). Rebecca Nowacek and Brad Hughes point to how adopting these behaviors involves “liminal threshold concepts, views that require not just cognitive understanding but sometimes profound reorientations of worldviews and even identities” (175). They describe the planning of initial tutor education as a process of identifying “which beliefs are the necessary building blocks for the rest of our work” and which “can be further explored during longterm professional development” (175).

Part of the challenge of tutor training, as Nowacek and Hughes acknowledge, is that understanding some of the necessary building blocks is “not simply a matter of flipping a light switch from off to on; rather, it is a cognitively (and sometimes emotionally) complex emergent understanding” (182). Mark Blaauw-Hara et al. point to this complexity in pushing for alternatives to the threshold metaphor that rely less “on the relatively quick transition between one space and another” (6). Regardless of the language or metaphor employed—habits of mind, a set of behaviors, or liminal threshold concepts—this discourse reflects the contention that tutor education should consider a tutor’s orientation to the work alongside the development of skills.

Adding to this discussion, we use the term disposition to emphasize the “cognitive and affective attributes that filter one's knowledge, skills, and beliefs and impact the action one takes” as a tutor. Lisa Cahill et al. persuasively demonstrate the value of a writing tutor training program that offers deliberate instruction in the realm of dispositions, or what they call “core principles” made up of both core beliefs and habits of mind. Cahill et al. identified habits of mind and core beliefs they wanted tutors to demonstrate and be guided by in their work and then revamped their tutor education program to directly address these habits and beliefs. They found that making these core beliefs explicit helped tutors think more critically about their work, guided them in challenging moments when working with writers, and provided shared language with which to discuss writing together.

Our study extends out of this premise that dispositions influence effective tutoring and that tutor education programs should be mindful of the dispositions they yield. Yet, we also recognize the challenge of assessing dispositional development. As Bruce Bowles reminds us, “assessment tells us as much about what we value in our programs as it does about the performance of our programs” (7). As we considered revisions to our own program, we wanted to first understand the connection between training activities and dispositional development. Of course, this connection is not always as straightforward as it might seem—assessing self-efficacy can reveal a “strange loop,” where “effects [can] appear disproportionate to their causes” (Comstock 17). Rather than articulate the dispositions we wanted tutors to develop and reorienting our program around that, we sought first to identify the effective dispositions tutors were already demonstrating by the end of their initial training and then attempt to track the training experience and determine which components of our current program seemed to influence that development. Essentially, we set out to identify what parts of our existing training program helped tutors develop dispositions that made them compelling collaborators. How did the tutor in the above epigraph, for example, come to see themself as first and foremost “connecting with others”?

Method

To identify tutors who seemed to successfully adopt a dispositional focus on writers, we turned to the culminating assignment of our initial training experience: a tutoring philosophy statement articulating the what, how, and why of their approach to tutoring. As the written product of our training program, this tutoring philosophy statement provides a residual artifact that we could use to consider the dispositions tutors possessed at the conclusion of their initial writing center training. While the articulation and execution of a philosophy are separate, the articulation is a start—a clear picture of what the tutors are aspiring to at the end of their initial training. Using the philosophy statement to identify tutors who appeared to have developed a compelling disposition, we could then consider additional written artifacts that the identified students created throughout the program to further track what parts of their training experience seemed to cultivate these dispositions.

In “Ongoing Writing Tutor Education: Models and Practices,” Julia Bleakney suggests that assessment of tutor education “should address everything tutors experience (including working in the writing center, as well as attending meetings, being observed, etc.) that helps build their expertise.” Given the range and abundance of reflective writing assignments throughout our training program, this archive of reflections provided the closest thing to a real-time record of “everything tutors experience.”

The next question was how to, or rather who should, conduct the assessment of these written artifacts. While the virtues of assessments that “privilege student perspective” are well established (Buck), there is a surprising lack of tutor involvement in assessment projects beyond reporting on their own experience. Typically, student perspective is ascertained through self-assessment tools like tutor surveys (Bleakney). There are far fewer published instances of tutors actually conducting assessment efforts themselves. However, in many cases, peers are best equipped to track and understand the experience of their colleagues (Topping 22).

As the writing center director, I (Tyler) was aware that my own experience facilitating the training might get in the way of grasping the tutors’ perspective on and experience in the training program. I was intrigued by the potential insights a tutor-led assessment of our training program might yield. I share Andrea Rosso Efthymiou’s sense of often feeling “taken aback by the keen way undergraduate staff make sense of their work without access to the same language and frameworks that we [administrators] have” (14). Efthymiou makes a case for considering “what knowledge a writing center administrator can gain from paying attention to tutors' frameworks for sensemaking alongside writing center administrators' own research-based frameworks” (14). The project described here begins with this same logic, using tutors’ language in tutor philosophy statements and written records to better understand their sensemaking journey. However, it extends that focus on tutor sensemaking to also include the interpretive assessment process itself. What knowledge is revealed by tutors paying attention to their fellow tutors’ frameworks for sensemaking?

I realized that experienced tutors, who had all gone through the training themselves, would be especially informed readers of their peers’ training experience. Attempting to center student perspectives in the assessment of our program, I chose three undergraduate tutors of varying experience—two years removed from their initial training, one year removed, recently completed—to conduct the assessment. After they each identified a compelling tutor philosophy statement, they then tracked the archive of their chosen peers’ journey to discern the elements of our tutor training program that seemed most significant to that specific tutor’s development. What follows is the record of their assessment and results. The insights gleaned from these case studies collectively exemplify the valuable contribution tutors can make in the assessment process by illuminating the experience of their peers. This research received IRB approval and was conducted in accordance with our institution’s human research guidelines.

Creating the Case Studies

We three undergraduate tutors (Madilyn, Gabbie, Olivia Drew) were presented with thirty de-identified philosophy statements written by thirty tutors enrolled in the training program from the previous academic year. We were tasked with reading through all of them to choose one that stood out in terms of its resonant portrayal of a tutor who possessed compelling writing center dispositions. Or in the words of the writing center director: which of these writers seems like a tutor you would want to work with if you were coming into the writing center with your own work? Once we selected a tutor based on their philosophy statement, we were provided with the rest of the chosen tutor’s written record from the 15-week training program, which included weekly reading/reflection summaries and weekly work reports.

The expertise we brought to the table was not only our proximity to the training program we were evaluating, having gone through it ourselves, but also our daily operations in the center and what type of dispositions we recognized as valuable on the tutoring floor. As students trained in literary analysis, we elected to employ a close reading approach to evaluate the tutors’ evidence trail. Like Harvey Kail’s reading of writing center manuals “as if they were narratives,” we similarly read the paper trail left by new tutors in training, focusing on “their story rather than focusing exclusively on their exposition and advice” (74). We scrutinized moments of triumph—where the tutor seemed to grasp writing center pedagogy and evince self-efficacy—and moments of struggle—where the tutor expressed concern and a disconnect seemed evident. Our inquiry was guided by a careful focus on what aspects of our training program facilitated epiphanies. Additionally, we looked for comparisons between the ideas articulated in the philosophy statement and these same ideas in the written record, trying to see how these various concepts developed and evolved throughout the entirety of the training program. Ultimately, we tried to track the tutors' growing sense of self-efficacy throughout their training and identify which parts of the training program facilitated their dispositional development.

The product of our analysis is ultimately three separate case studies that narrate distinct journeys throughout our training program. The tutor journeys depicted in these case studies are not representative of any larger whole in the sense of being picked according to demographic background, pre-existing preparation, or any other criteria along these lines. Rather, they were selected on the basis of their de-identified philosophy statements that seemed representative of tutors who exited the training program with a compelling approach to tutoring. One limitation of focusing on successful tutors is the potential to overlook what struggling tutors can tell us about ways to develop our training program. However, we wanted to first identify which parts of our training program prove effective at developing collaborative dispositions and therefore should be included in future iterations.

The three case studies below identify those parts of the training program by synthesizing and detailing the experience of new tutors. In narrating individual experience, case studies are well-suited for communicating the subjective nature of dispositional development because they “examine the experience of particular people in particular contexts as they engage in authentic activities” (Severino & Deifell 32). In addition to identifying training components that help develop dispositions, these case studies are also beneficial for the insight they provide into how these tutors navigate the training experience generally. The case studies reflect the rich intricacies of the new tutor experience while highlighting which elements of the training program prominently influenced these tutors’ dispositional development. In particular, these case studies reveal the value of combining practice with theoretical instruction, the importance of creating a community of practice, and the significance of metacognitive exercises.

BYU’s Training Program

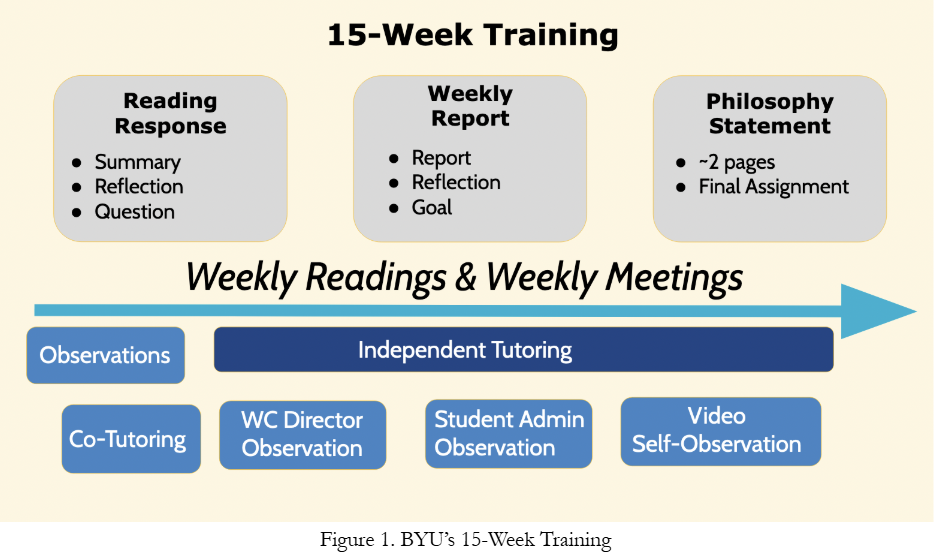

To contextualize the case studies, here is a brief overview of the training program we are assessing. At BYU’s Writing Center, new tutors are trained in a 15-week program (see fig. 1). The first few weeks of this training include new tutors observing and then co-consulting with more experienced tutors. Beginning around week 5, new tutors are then observed in a solo consultation by the writing center director, who confirms their preparation to tutor independently.

Throughout this process, new tutors attend weekly staff meetings and class meetings as they acquire familiarity with fundamental tutoring skills such as scaffolding, in addition to training centered on working with alternative genres, writing courses specific to BYU, multilingual writers, and other various student identities.

As shown in Figure 1, new tutors complete a number of assignments over the course of their training, such as weekly reading responses, weekly work reports, and various observations. These assignments encourage new tutors to engage with tutoring material, account for the time they spend in the writing center and offer a space for metacognitive reflection regarding the development of their tutoring practices.

New tutors conclude their training by synthesizing the tutoring knowledge they have acquired, relying on informative readings, classes, reflections, work reports, or other discussions they have had with peers in order to articulate their personal approach to tutoring. These tutoring philosophy statements are then shared with their fellow new tutors at the conclusion of their training.

Tutor 10: Case Study by Madilyn Abbe

Justification

Although I’m three years removed from my own training program, I’ve been fortunate to continue inhabiting the new tutor sphere. At our writing center, our student administrator position pairs a seasoned consultant with new interns to train, mentor, and guide them. Working in this position, I’ve repeatedly witnessed individual tutor growth throughout the process of the training program. After reviewing thirty philosophy statements, I selected Tutor 10. I felt drawn to this philosophy statement because the tutor aptly articulates the purpose of the writing center and the writing tutor, capitalizing on the trope of being so much more than a red pen. With this metaphor, Tutor 10 emphasizes tutors as conversationalists, something much more than mechanical instruments. Their philosophy articulates the ways that tutors must engage students through meaningful conversation. As Tutor 10 acknowledges, oftentimes college students struggle with writing because they can’t conceive of an audience other than a professor. For Tutor 10, the tutor fills the space of the audience, bridging the missing gap. By focusing on peers over final products, students are no longer alone. Collaborating with a tutor ultimately facilitates their development as writers.

Tutor 10’s philosophy statement intrigued me to learn more about what enabled them to illustrate the dichotomy between the “red pen” and the writing tutor. I was interested to discover what memorable moments of collaboration taught them how to effectively work with student writers. Tutor 10’s dispositional focus on student writers primarily developed out of their experiences balancing their enthusiasm for writing center theory with the challenges of tutoring actual humans and all the variability they present.

Narrative

Preparation

Stress and an eagerness for writing center theory characterizes Tutor 10’s preparation phase. The underlying stress is understandable considering that the preparation phase introduces myriad tips to navigate a completely new work environment. In the midst of newness, Tutor 10 finds comfort in theory. Their eagerness for pedagogy’s theoretical grounding includes different approaches to tutoring and ways to conceptualize the space. For the first week of the training program, it’s evident that Tutor 10 feels overwhelmed and self-conscious. Their comments emanate a layer of stress as they mention the initial difficulty of “figuring out how to clock in” and the overwhelm of digesting a “copious amount of information.” Yet, it is the human interaction with other writing center tutors that provides some relief. In addition to “a familiar face who answered a lot of my questions,” Tutor 10 notes how “all of my interactions with consultants were positive.” Hearing about other tutors’ trials and triumphs in the training program assuages their feelings of inadequacy.

One thing that stands out from the preparation phase is how eager Tutor 10 is about the theory readings and discussions. During this phase, these readings primarily conceptualize the purpose of the writing center and the writing tutor as well as introduce new tutors to scaffolding methods. Phrases like “I whole-heartedly agree” indicate the extent to which theory coincides with Tutor 10’s own viewpoint. Tutor 10 even directly quotes and names theorists in their personal reflections. They also attempt to incorporate concepts learned from theory readings into practical application with their weekly goals.

While conducting observations, Tutor 10 takes a magnifying glass approach. Before independent tutoring, new tutors observe seasoned consultants during a session. New tutors take notes during the consultation and later interview the seasoned consultants about what strategies they chose and why. Most of Tutor 10’s notes from observations highlight concepts from theory readings. Yet, rather than hoping to apply the theoretical approaches they’re witnessing in action, Tutor 10 seems to highlight whatever is already familiar to them. Observations seem to be a way to identify theoretical concepts more than learning skills for their own tutoring.

The synthesis of theory and practical observations lead Tutor 10 to eloquently articulate an early conception of what they believe will be helpful to the students they work with: “Not every student is going to desire help with the composing process and strategies of cognitive/motivational scaffolding may not change a student’s life, but theory helps guide us to make beneficial choices.”

Tutoring

Tutor 10 leaves the preparation phase with excitement for the theoretical part of the writing center. This excitement stays strong into the tutoring phase as Tutor 10 seems to hold tightly to theory as they begin tutoring for the first time. Additionally, in the tutoring phase, the stress Tutor 10 exhibited at the beginning of the training transfers into a different kind of stress. Now, instead of stressing about clocking in and navigating the writing center, Tutor 10 expresses concerns about tutoring approaches and the limits of theory.

While in the tutoring phase, theory still functions as a significant factor for learning and development. Tutor 10 often mentions how a theory reading dispels fears or how they frequently reflect on theory readings during the week. Sometimes Tutor 10 even wishes for extra time to reread theory because “so many of the students I meet with could be benefited by instruction on these chapters.” Tutor 10 also expresses an acute and insightful awareness of the role of writing center pedagogy: “In my reading, it stressed the fact that writing center pedagogy allows for us to tailor our time to the individual needs of students.” These comments indicate how Tutor 10 sees a direct correlation between theory reading and writing center work.

Interestingly, it's during this stage that Tutor 10 begins to push back slightly against theory. When I read this, I was surprised because theory seemed to be Tutor 10’s foundation up to this point. As Tutor 10 begins their own independent tutoring, it seems they’re beginning to realize the discrepancy between the ideal (theory readings) and the real (in-center practice). Now that Tutor 10 has emerged from the bubble of just discussing theoretical tutoring, Tutor 10 begins to question the universality of theory. In response to a reading about the theory of asking questions, Tutor 10 posits, “Is there a limit to asking questions? When can you tell if asking questions is frustrating a student?” Here, Tutor 10 recognizes that while theory offers an approach, the student doesn’t always respond in the way that theory anticipates. Perhaps as a result of the experience they’ve had on the tutoring floor, Tutor 10 is beginning to realize that theory isn’t a panacea.

Having the writing center director observe Tutor 10 was a breakthrough for them. Before students are cleared for independent tutoring, the writing center director observes one of their consultations. Afterward, a discussion allows the new tutor to metacognitively express their rationale behind tutoring choices. Additionally, the writing center director offers the new tutor advice about how to improve. Tutor 10 “really enjoyed” getting observed, and it seems this observation was instrumental in filling in gaps and learning new things. Interestingly, while we might expect Tutor 10 to use theory language to articulate what they learned, Tutor 10 recounts the experience in solely strategic, practical terms. This may indicate that, at this stage in their journey, Tutor 10 hasn’t successfully integrated theory into practice and vice versa. Tutor 10 can read theory and identify what aspects they enjoy and want to incorporate as well as observe other tutors and recognize how theory intersects with their practices. But when it comes to Tutor 10’s own tutoring practice, there’s a disconnect. The two halves of the divide, in-center practice and theory, are still separate. While Tutor 10 has conceptualized how theory fits into in-center practice, they have yet to connect the dots.

Growth

The growth period was a crucial week for Tutor 10. In this period, Tutor 10 strongly pushes back against theory, more than we saw in the previous phase. In one instance, Tutor 10 questions, “I understand that this is the ‘theory’ of asking questions, but what if a student fails to respond to social-coordinating questions? Should we become more direct to facilitate the consult?” Here, Tutor 10 continues to navigate between the push and pull of the ideal vs. the real world. Yet, this pushback becomes helpful in navigating the practical tutoring experience of the writing center.

During this period, Tutor 10 vocalizes a heightened level of confidence. The significance of Tutor 10’s professed self-confidence is augmented by the fact that Tutor 10 mentions having a frustrating consultation. I was impressed by this positive attitude considering that this was the first time Tutor 10 had ever admitted to having a bad consultation, yet the negative interaction becomes a learning experience rather than an event that dampens their confidence. Tutor 10 identifies what factors made the difference: their increased self-efficacy comes from both a synthesis of theory (“After reading through some genre guides I feel a lot more confident jumping into consultations'') and real-life experience (“I feel like I am beginning to feel a lot more comfortable in the writing center the more consultations I get under my belt”). Thus, the combination of prior theory readings and practice is crucial for Tutor 10.

Additionally, Tutor 10 was observed by a student administrator. Compared to the writing center director observation where Tutor 10 completely omits theory when describing what they’ve learned, this time Tutor 10 integrates theory into their reflection. Tutor 10 is now able to not only see the connection of theory to practice but look at their own practice and explain their choices in terms of theory. At this moment, theory becomes not just theory in and of itself. Instead, theory is a tool that helps tutors recognize the student and help them in the way that they need it the most. Tutor 10 closes out the tutoring phase by commenting that writers are much “more than a red pen.” Their takeaway message of the training process puts it simply: “just have a conversation.”

Results

Tutor 10’s journey exemplifies the oscillating eagerness new tutors experience when interacting with theory. Tutor 10 starts the training program with heightened attunement to theory discussion. Yet once they have to apply this theory to real writing center sessions, Tutor 10 begins to push back against theory, having learned that consultations can’t always be encapsulated or diagnosed by the pages of a theory textbook. In the end, Tutor 10 is able to return to their theory eagerness, but this time with newfound nuance for the purpose that theory holds in the context of writing center practice—namely that rather than being prescriptive, theory suggests diverse practices to help a tutor collaboratively engage with a student. Tutor 10’s training experience demonstrates the value of combining practice with theoretical instruction in helping new tutors develop a collaborative disposition. As Tutor 10 contextualized theory through their deliberate practice, they gained a sense of themselves as a thoughtful conversation partner making informed choices in response to the student’s needs.

Tutor 12: Case Study by Gabbie Schwartz

Justification

Being only two years removed from my training, it’s easy to recall the enthusiasm I had as a new tutor and my rigorous determination to ensure each of my sessions became a collaborative wonder. But as time passed, I found my original vigor tempered by the realization that some sessions do not always go according to plan. I uncovered similar sentiments in Tutor 12’s philosophy statement and became drawn to their vision of tutoring as “intellectual friendship,” a term they borrowed from the Dutch philosopher, Desiderius Erasmus.

In applying intellectual friendship to the writing center, Tutor 12 emphasized the unique peer-to-peer position tutors have with students. As much as tutors are teachers, they are simultaneously students themselves, constantly learning from those they teach. But Tutor 12 also recognized the difficulty of realizing this theory, hence their philosophy statement explained how they maintained the delicate equilibrium between their theoretical aspirations and the occasionally hectic nature of the lived tutoring experience. For Tutor 12, this became a matter of collaboration, conversation, and connection. Collaboration referred to “moments of mutual learning,” conversation focused on discussions that fortified the learning experience (this could include instruction, questions, or encouragement), and connection was the process of helping students see the links between themselves and the skills they acquired in the consultation.

With these definitions in mind, I analyzed the reading responses and work reports Tutor 12 had produced, looking for experiences which informed their understanding of collaboration, conversation, and connection. In short, my goal was to understand how Tutor 12 came to see and treat students as intellectual friends. It seemed interpersonal opportunities—moments of interaction with their fellow tutors, the writing center director, and the students they tutored—proved most valuable to Tutor 12. These interactions helped them practice tutoring as a form of intellectual friendship.

Narrative

Preparation

It was clear that Tutor 12 entered the training program with an initial understanding of intellectual friendship, even if it was never directly named. They made it their goal to engage with other tutors and observe how they “put the readings… into practice.” As such, they constantly engaged with other tutors, seeing each of them as thought-partners—people they were enthusiastic to collaborate with and learn from. This collaborative desire only continued throughout their training, as many tutors and their advice make guest appearances in Tutor 12’s reflections. One tutor informed Tutor 12 that writing consultants strive to “help writers first and writing second.” Tutor 12 interpreted this to mean that tutoring sessions were to be treated as “team-like experiences,” but they believed their role in this experience was not necessarily to view students as peers they could collaborate with, but rather to teach students how to write by focusing on filling their knowledge deficits.

Tutor 12 understood intellectual friendship when applied to their fellow tutors, but they had yet to apply that theory to student writers. They could not yet understand how they should be interacting with students, as evidenced by the litany of “how” questions featured at the end of their reflections: “How do consultants not get stuck in a rut of asking the same questions… How can I really make every day feel different even if the papers or the issues are repetitive?” The “information overload” was of increasing worry for Tutor 12. They wrote, “I’m going to be honest, this information has been a bit overwhelming for me to imagine putting into practice. How are we supposed to juggle all of these thoughts… What’s theory and what’s applicable.” Much like Tutor 10, there was a clear distinction between the ways Tutor 12 wished to tutor—an idealized theory—and having to actually tutor—the application and practice of that theory.

Within this same week, however, Tutor 12 found solace from another tutor who told them, “Your goal isn’t to diagnose the writer’s problems.” This reminder resolved Tutor 12 of feeling “overwhelmed by the idea of someone coming in with a paper that doesn’t meet the rubric in the way I would write it.” It appeared that Tutor 12’s worries were partially self-imposed. Their early conceptualization of tutoring led them to believe that they needed to fill in knowledge deficits, and they would do so by teaching student writers how to think and write like them. But as Tutor 12 was beginning to understand, teaching student writers to respond to the rubric by thinking and writing in ways not their own could hardly be called tutoring. While this realization did not provide an immediate resolution to the seemingly disparate elements of theory and practice, it did help Tutor 12 solidify what a tutor might not be and what a tutor might not do.

Tutoring

In the tutoring period, Tutor 12 began to navigate the divide between theory and practice as they tested their understanding of theory during their consultations on the tutoring floor. They were now free from the belief that they had to teach student writers to write like them, and this allowed them to glean an important insight: “my attention has shifted from memorizing theory and bullet-pointing session agendas to attempting to identify, work with, and improve upon the writing processes of the student in front of me.” Tutoring was no longer about finding a way to produce the perfect writer, whose new writing style would be modeled after Tutor 12’s. Instead, Tutor 12 began to actualize collaboration—learning how to see and work with the student in front of them.

This change in perspective was not entirely smooth, however, as Tutor 12 admitted to several of their consultations being “a little shaky.” After being observed by our writing center director, Tutor 12 brainstormed some potential solutions, realizing that their issue centered around question usage: they could be asking more questions to help “the cognitive connections flow even stronger” and “have the student come up with their own ideas.” Their commitment to this strategy was reinforced following the student administrator’s observation of Tutor 12 and their subsequent debriefing. Tutor 12 asserted that “by making themselves an active participant in the questioning[,] the tutor can better help the student try to say what they want to say and then move them through their thinking ‘slowly and incrementally.’”

Drawing on their own intellectual friends, Tutor 12 began to deepen their understanding of intellectual friendship as a theoretical approach while grounding that theory in actionable practices. Questions were a helpful tool for placing the student at the center of the consultation because questions encouraged the students’ own metacognitive process. As Tutor 12 engaged students with these questions, they discovered that students were insightful peers, able to think and write on their own terms.

Growth

Tutor 12 was beginning to truly understand tutoring as a form of intellectual friendship, but there was still more to learn. One consultation in the growth period proved especially formulative, as it would make its way into Tutor 12’s philosophy statement. Tutor 12 initially struggled to discern how best to work with the student in front of them. The questioning strategy they had been successfully developing before was met with silence, and—taking note of this—they realized they had to adjust. The shift was subtle, as they began using “words such as ‘we’” while “providing an emotional support behind the questions” they asked. But this slight change drastically improved the session and led Tutor 12 to another important insight, one that reflected a more nuanced understanding of intellectual friendship. They stressed that tutors had “to learn alongside the student” with “humility and willingness.”

Despite the initial difficulty of the consultation, Tutor 12 had successfully enacted Erasmus’s theory in-session. This was quite different from the beginning of their training, where they focused primarily on how to develop student writers in accordance with their own writing standards rather than work with student writers as peers that had ideas and abilities of their own.

The following week, Tutor 12 read Steve Sherwood’s article, “Censoring Students, Censoring Ourselves: Constraining Conversations in the Writing Center.” They admitted, “I do worry about this idea of the right kinds of censorship and that I’m creating machines out of human beings. It’s probably my biggest fear about being a tutor, actually.” Over the course of their tutoring journey, Tutor 12 had become afraid of unintentional censorship, afraid of becoming a teacher who created robotic pupils that spat out carbon-copies of Tutor 12’s own writing style. They instead believed that a tutor should work alongside the student, prompting them with questions and encouragement, thereby allowing them to have their own “lightbulb moments.”

Reflection

In the final week of their training, Tutor 12 reflected on their time in the writing center through William Cronon’s “Only Connect” and Kenneth Bruffee’s “Peer Tutoring and the ‘Conversation of Mankind.’” Tutor 12 had been learning that intellectual friendship rests in a relationship where both tutor and student work as equals toward a common goal. As a result, tutors should “generate good thinking through good conversation[,] and good conversation comes from good community.” This was the role they imagined for themselves—a tutor who could facilitate a community founded on collaboration, communication, and most importantly, connection.

It had been connecting with peers and advisors that helped Tutor 12 understand writing center work. They realized that when tutors extended this same connection to the students they worked with, they could simultaneously “nurture human freedom and serve the human community. We make scholarship practical for new learners, bring voice to new ideas, and help new minds contribute to unending conversations—and we do so as peers.” This was, in effect, the true distillation of their philosophy statement. The pieces I had seen from the beginning had—funnily enough—connected with one another when Tutor 12 entertained the role of connection itself.

Results

Tutor 12 had an inkling of intellectual friendship when they began their training, often learning from other tutors and administrators. But in many ways, they did not yet see how a student could teach them. After all, they were the writing tutor with writing expertise. It was not until they were placed face-to-face with the student that they began to realize how much the student could teach them and that they were developing “a network of intellectual friends… who always feel comfortable coming back to teach me as much as they expect to be taught.” As Tutor 12 connected with student writers in the same way they had already connected with their fellow tutors and administrators to improve their tutoring, they developed a more expansive understanding of their role as a tutor. The writing center and the connections formed therein became a vibrant network of collaboration and intellectual friendships between tutors and student writers alike.

In considering Tutor 12’s development through the initial training, the most significant component of that training which developed their collaborative disposition was the consistent opportunities they had to interact with others. These interpersonal opportunities—between their fellow tutors, student leaders, administrators, and eventually the student writers they worked with—helped Tutor 12 gain a sense of themself as a tutor. Like Tutor 10, Tutor 12 took their engagement with theory seriously, but they made sense of implementing theory and practice through their conversations with colleagues. Their experience speaks to the value of creating opportunities for tutors to interact with each other and build a community of practice where they “talk shop,” digesting together both what they are reading and the experiences they are having on the tutoring floor. As Tutor 12 puts it, “The more I learn, the more I realize is left for me to learn… the more you know, the more you know what you don’t know. You know?”

Tutor 22: Case Study by Olivia Drew Swasey

Justification

As the most recent graduate from our tutor training program, I felt the lack of removal while selecting my fellow tutor, Tutor 22. Tutor 22 skillfully developed their own personal philosophy, drawing inspiration from the theme "The Road to El Dorado," derived from the popular DreamWorks film. In their metaphorical framework, Tutor 22 positioned themselves as a knowledgeable guide, adept at assisting others in their pursuit of valuable insights. Essentially, Tutor 22 recognized, upon crafting their philosophy statement, that the key to a successful writing center lies in prioritizing the needs of others, rather than relying solely on a prescriptive or map-style approach. However, I was intrigued by how Tutor 22 managed to develop such a nuanced understanding of the subject matter, despite appearing to have devoted minimal introspection to the assigned readings. This curiosity prompted me to explore Tutor 22's journey through the training program and unravel the elements of the training program which did influence their reflection. Upon careful examination of the training components emphasized by Tutor 22, it became evident that they acquired their personal philosophy through purposeful activities deliberately designed to teach the underlying theory, rather than solely relying on theoretical study. These activities, when integrated with deliberate practice, interpersonal engagement, and metacognitive exercises emerge as essential elements of their tutor training experience.

Narrative

Preparation

Tutor 22’s El Dorado analogy was in the making from week one of the program. They described consulting as a “method of connection to the writer through discourse over the writing” (1). This is their first reflection in the course, and they are already showing signs of their personal commitment to collaboration and process-oriented tutoring. However, directly following this statement is this question: “Is there a way to prioritize edits if I run too short on time to get the writer’s paper where it needs to be?” Questions like this frequent Tutor 22’s reading reflections, hinting at how the insights they gain from theoretical readings never quite overshadow their sense of themself as an editor of student writing.

In contrast, their work reports (which feature mainly activities and consultations) offer a much better reflection of how they ultimately came to understand their role in a more collaborative sense. The activities that Tutor 22 reported on in their work reports were accompanied by worksheets of questions designed to facilitate reflection. These metacognitive exercises seemed to most significantly alter Tutor 22’s preconceived notions of tutoring and forge a desire to replace their editorial mindset with collaborative experience, as they’ve seen more experienced tutors do.

This is not to say Tutor 22 overlooks the theoretical readings completely; they are aware of the value theory has in the writing center space to a certain degree. However, they recognized the importance of writing center literature only after being presented with an activity designed to apply the principles in low-stakes scenarios. Tutor 22 did not maintain, in other words, the enthusiasm or proclivity for theory that both Tutor 10 and Tutor 12 seemed to bring to their initial training. Once they developed an appreciation for the value of theoretical understanding, they had to learn how to harmonize theory with application.

Tutoring

Before starting their time on the floor, each new tutor must have a session observed by the writing center director. After the session, the director will point out points of connection between theory and their application and help the new tutor create goals. Tutor 22 clearly valued their director's observation, saying “[the director] helped me…better teach transferable writing skills.” This activity and the following metacognitive exercise unpacked theoretical concepts and refocused Tutor 22 on collaborative goals.

I anticipated that this reflection would be the tipping point for Tutor 22, as it mirrored the same sentiments they express in their philosophy statement; however, this activity was the only activity during this tutoring period that included a metacognitive exercise, and therefore the only moment of connection. Instead, Tutor 22 turned their focus to correction due to the structural-based readings they were introduced to. They viewed readings on grammar and style as personally informative rather than helpful to their tutoring experience, stating “By understanding the patterns that create cohesive writing, I’ll be able to better advise on…my own work.” This quote summarizes Tutor 22’s focus on learning grammar and how they used every reading involved in it to discuss how it would improve their own writing. While it never explicitly appears in their final philosophy statement, Tutor 22 believes self-correction, or their own knowledge, is a vital responsibility of the writing center and thus cannot help to overemphasize it when faced with possible knowledge gaps.

They also let the editorial mindset take over their tutoring of others. While Tutor 22 determined that the “two main responsibilities of a writing consultant” are connection and correction in Week 2, in Week 7 they choose to focus on only one of those responsibilities, stating: “...after all, half the point of the Research and Writing Center is to help student writing become more concise and understandable.” Five weeks later connection has become a concept, rather than an outright responsibility of the tutor. Thus, correction overcame connection, and Tutor 22 returned to their editorial mindset.

Growth

Tutor 22’s growth advanced in large part due to one specific metacognitive activity: the videotaped session. This videotaped session was the most formative activity Tutor 22 experienced during the course of the training. The assignment’s inherent position, as the trainee’s first experience watching how they connect theory and on-floor application, helped Tutor 22 bridge the gap between their strong inclination towards correction and their earlier goal of connection so quickly.

One signal of the videotaped session’s importance to Tutor 22 was their choice to include its impact in both their work report and reading reflection; they discussed the results of their review of the footage, taking full advantage of this metacognitive exercise. After reading Mackiewicz & Thompson, “Questioning in Writing Center Conferences,” Tutor 22’s reflection featured the clearest connection between their reading and real-world sessions. Referring to their videotaped session, they noted: “I’m really glad we read this essay this week because…I did not even realize I was employing these strategies after the fact…sometimes not sure if I’m absorbing the advice from our reading. I think I am, though I can definitely do better.” Mackiewicz & Thompson’s article is featured early in Tutor 22’s philosophy statement; this signals its importance in Tutor 22’s understanding of writing center praxis and their own competency.

After realizing their competency, Tutor 22’s entire demeanor changed. Their self-corrective tendencies all but disappeared after they noticed that the skills they were trying to develop were “within them all along,” and their focus landed on helping promote that same understanding in the students they tutored. In their words, their goal shifted to “[becoming] more student-oriented”; they started calling their work fulfilling and motivating, and they expressed finally feeling settled in the writing center. They got enthusiastic about their work in a way they never had before, saying “I [want to] help writers be proud of their work and help them recognize the value of their writing.”

Reflection

After this breakthrough moment, Tutor 22 was left open to consider their training trajectory through the lens of a philosophy statement. Tutor 22’s choice to answer this question by comparing the writing center to the mythical city of El Dorado is compelling. First, they compared the community's interest in writing to a search for lost treasure, a parallel that highlights their mastery over the common “initial terror” between process and product that many new tutors face. Their philosophy statement condemns this correction perspective: “Often, the only connection [students have] seen their words make is with a professor’s ruthless red pen. In a sense, getting a graded essay back is a lot more like receiving a verdict than feedback.” Tutor 22 understands what parts of theory and practice “encourage the collaborative atmosphere of a consultation, assuring the student that their thoughts and voice matter.”

It is the second comparison to El Dorado, however, that reflects the collaborative disposition Tutor 22 developed by the end of their training. The journey to the writing center is a journey to a treasured community, yes—but it is also a journey to a person, as El Dorado was recently discovered to be. Tutors are roadside opportunities for connection and tools for helping students see their writing potential inside themselves. Essentially, each student’s journey to and through the writing center is centered on discovering the ultimate treasure: their future writing talent, and Tutor 22 wants to be a facilitator of that knowledge: “I work at the Research and Writing Center to help students. I don’t think that was my initial reason for coming to work here, but it is now.”

Results

One of the most interesting things about Tutor 22’s training is the contrast between different dispositions that the tutor displays throughout their experience. As they develop a disposition of collaboration, they are led to confidence and focus. Within this, the most helpful things for this tutor seemed to be the metacognitive exercises and activities that encouraged them to consider alternative ways to make use of and apply the theoretical formulations they were encountering in their reading. Tutor 22’s early emphasis on fixing a student’s paper over seeking to understand a student’s perspective reflects in some ways a desire for a tangible practice that simplifies the tutor’s role. Although writing center theory aims to expand a tutor’s sense of that role, the editor mentality remained alluring for Tutor 22. It took more than reading exercises to orient them to a more expansive understanding of their role as a tutor. Their experience suggests the value of metacognitive activities in initial tutor training. These activities helped Tutor 22 branch out into the possibilities of their position. Their final philosophy statement reflects the disposition of a tutor who is confident in exploring different ways to effectively engage with student writers, ultimately pointing them towards an increased love of writing, something we can all agree is a true treasure.

Conclusion

The above case studies reveal the range of experiences that tutors have in their initial training and effectively demonstrate that dispositional development is, to borrow Nowacek and Hughes’s language, a “cognitively (and sometimes emotionally) complex emergent understanding” (182). While we do not wish to overgeneralize the applicability of these case studies, we do want to emphasize their value in helping us understand how dispositions are developed. Though these tutors had overlaps in their experiences, and none of them had a linear development, they each had triumphs and setbacks at different periods in their training that makes the training process seemingly impossible to predict and therefore mechanize. The individualistic nature of each tutor’s journey reiterates the subjective nature of dispositional development.

In terms of identifying potential connections between training activities and dispositional development, the tutors studied here seemed particularly aided by opportunities to wrestle with theory in the face of real-world practice, the chance to integrate themselves into a broader community of practice, and the utility of deliberate metacognitive exercises. While we can’t generalize from these three case studies to suggest that these prominent components always influence dispositional development, we are convinced that these are components we’ll continue to emphasize in our own training program. Part of the reason is that, based on the experience of these three tutors, metacognitive and interpersonal opportunities along these lines seem to push tutors into the realm of dispositions, where they must think about the ways they filter their knowledge, skills, and beliefs to accomplish the task before them. This then might be the larger takeaway of our study for writing center administrators involved in tutor training. These case studies convincingly suggest the value of training activities designed to place tutors at the intersection of their practical experience and conceptual understanding. It is in learning to navigate that intersection that tutors blend cognitive and affective attributes that shape their sense of themselves as tutors. These developed dispositions then filter their knowledge, skills, and beliefs in ways that help them effectively collaborate with student writers. As the enthusiasm of the tutor in the opening epigraph suggests, this job becomes “much more” when tutors come to feel that they understand “the point.”

Works Cited

Blaauw-Hara, Mark, et al. “Thinking Past the Portal: Threshold Concept Metaphors for Diverse Learners in Disparate Disciplines,” Currents, vol. 16, no. 2, 2025, pp. 6-21. https://webcdn.worcester.edu/currents-in-teaching-and-learning/wp-content/uploads/sites/65/2025/01/Thinking-Past-the-Portal.pdf.

Bleakney, Julia. “Ongoing Writing Tutor Education: Models and Practices,” How We Teach Writing Tutors: A WLN Digital Edited Collection, edited by Johnson, Karen G. and Ted Roggenbuck, 2019, chapter 4, https://wlnjournal.org/digitaleditedcollection1/Bleakney.html.

Bouquet, Elizabeth H. and Neal Lerner. “After ‘The Idea of a Writing Center.’” College English, vol. 71, no. 2, 2008, pp. 170-89. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/25472314.

Bowles, Bruce Jr. “When a Measure Becomes a Target: The Dangers of Using Grades in Writing Center Assessment.” WLN, vol. 49, no. 2, 2025, pp. 3-8. https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/wln/v49n2/v49n2.pdf.

Bruffee, Kenneth A. “Peer Tutoring and the ‘Conversation of Mankind.’” The Oxford Guide For Writing Tutors: Practice and Research, edited by Lauren Fitzgerald and Melissa Ianetta, Oxford UP, 2016, pp. 325-335.

Buck, Elisabeth H. “From CRLA to For-Credit Course: The New Director’s Guide to Assessing Tutor Education.” How We Teach Writing Tutors: A WLN Digital Edited Collection, edited by Karen G. Johnson and Ted Roggenbuck, 2019, https://wlnjournal.org/digitaleditedcollection1/Buck.html.

Cahill, Lisa, et al. “Developing and Implementing Core Principles for Tutor Education: Administrative Goals and Tutor Perspectives.” How We Teach Writing Tutors: A WLN Digital Edited Collection, edited by Karen G. Johnson and Ted Roggenbuck, 2019, https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/wln/dec1/Cahilletal.html.

Choi, Hee-sook, Nicholas F. Benson, and Nicholas J. Shudak. “Assessment of Teacher Candidate Dispositions: Evidence of Reliability and Validity.” Teacher Education Quarterly, vol. 43, no. 3, 2016, pp. 71-89. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/teaceducquar.43.3.71.

Comstock, Edward. “The Strange Loop of Self-Efficacy and the Value of Focus Groups in Writing Program Assessment.” Journal of Writing Assessment, vol 17, no. 2, 2024, pp. 1-20. https://doi.org/10.5070/W4jwa.252.

Efthymiou, Andrea Rosso. “The Medachtic Tutor: Jewish Discourse, Metaphor, and Undergraduate Tutors’ Sensemaking of Writing Center Work.” Sensemaking for Writing Programs & Writing Centers, edited by Rita Malencyzk, Utah State UP, 2023, pp. 11-22.

Holt, Mara. “The Writing Center.” Collaborative Learning as Democratic Practice: A History, NCTE, 2018, pp. 99-110.

Kail, Harvey. “Separation, Initiation, and Return: Tutor Training Manuals and Writing Center Lore.” The Center Will Hold, edited by Michael Pemberton and Joyce Kinkead, Utah State UP, 2003, pp. 74-95.

Mattison, Mike. “Heading East, Leaving North: Thoughts from the 2016 IWCA Conference.” WLN, vol. 42, no. 3-4, 2017, pp. 2-6. https://doi.org/10.37514/WLN-J.2017.42.3.02.

Malencyzk, Rita, editor. Sensemaking for Writing Programs & Writing Centers. Utah State UP, 2023.

Nowacek, Rebecca, and Bradley Hughes. “Threshold Concepts in the Writing Center: Scaffolding the Development of Tutor Expertise.” Naming What We Know: Threshold Concepts of Writing Studies, edited by Linda Adler-Kassner and Elizabeth Wardle, Utah State UP, 2015, pp. 171-185. EBSCO, https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/byu/reader.action?docID=3442949&ppg=206.

Rike, Cheryl J., and L. Kathryn Sharp. “Assessing Preservice Teachers’ Dispositions: A Critical Dimension of Professional Preparation.” Childhood Education, vol. 84, no. 3, 2008, pp. 150–53. Taylor & Francis Online, https://doi.org/10.1080/00094056.2008.10522994.

Severino, Carol, and Elizabeth Deifell. “Empowering L2 Tutoring: A Case Study of a Second Language.” Writing Center Journal, vol. 31, no. 1, 2011, pp. 25-54. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.7771/2832-9414.1722.

Thornton, Holly. “Dispositions in Action: Do Dispositions Make a Difference in Practice?” Teacher Education Quarterly, vol. 33, no. 2, 2006, pp. 53–68. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/23478934.

Topping, Keith J. “Peer Assessment,” Theory Into Practice, vol. 48, no. 1, 2009, pp. 20-27. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/40071572.

Wayda, Valerie, and Jacalyn Lund. “Assessing Dispositions: An Unresolved Challenge in Teacher Education.” Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, vol. 76, no. 1, 2005, pp. 34–41. Taylor & Francis Online, https://doi.org/10.1080/07303084.2005.10607317.