Praxis: A Writing Center Journal • Vol. 23, No. 2 (2026)

The Research Tax: The Hidden Costs of Publishing Underrepresented Knowledge

Sarah Rewega

University of Guelph

srewega@uoguelph.ca

Waed Hasan

University of Guelph

whasan@uoguelph.ca

Abstract

This article introduces the concept of the research tax to describe the additional intellectual, emotional, and institutional labour imposed on marginalized scholars within academic publishing. Building on Cedric Burrows’ “Black tax” and Sara Ahmed’s critique of performative diversity, we examine how Calls for Papers (CFPs) operate as gatekeeping texts that gesture toward inclusion while reproducing exclusion. Drawing on our positionalities as women with invisible disabilities, English as an additional language users, and scholars working in feminist, decolonial, refugee, and transnational frameworks, we conduct a critical discourse analysis of seven CFPs. Our findings reveal recurring patterns of topic omission, epistemic assimilation, limited structural support, and the containment of marginalized scholarship within special issues. We argue that these practices disproportionately burden graduate, precarious, Global South, refugee, and transnational scholars. The article concludes with recommendations for editorial accountability and structural change aimed at moving academic publishing beyond symbolic inclusion toward material equity.

In his article, “Writing While Black: The Black Tax on African American Graduate Writers,” Cedric Burrows coined the term “Black tax” to describe how Black students experience a charge “to enter and participate in white spaces,” one of which is academic institutions. Clarifying further, Burrows argues that African Americans have to work twice as hard to “rise above their situation” while remaining silent about racism to simply gain the same rights that white individuals already have (Burrows). Similarly, Alexandria Lockett’s article, “Why I Call It the Academic Ghetto: A Critical Examination of Race, Place, and Writing Centers,” expands on this tax, suggesting that it should be “broadly interpreted to include all sorts of ways people pay for their historical disenfranchisement” (24). As co-authors, we write from distinct but connected positionalities: both of us are women with invisible disabilities who use English as an additional language. One of us is white and a feminist scholar of the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, while the other is a third-generation Palestinian refugee whose research engages refugee memory and decolonial struggle. These identities are not background details but part of our method: they shape how we read CFPs, what silences we notice, and how we understand exclusion in academic publishing.

After several years in academia—submitting to journals that deemed our work as “unfit,” receiving silence as a response to our proposals, and reshaping our research to meet invisible standards—we began to feel the weight of this tax personally. We had arrived at an impasse: how do we continue to write, research, and publish in spaces that did not make room for us? This paper extends the concept of the “Black tax,” borrowing from Burrows’ initial framing and expanding it to articulate the lived experiences of many graduate students and others in academic circles. We name this the “research tax,” a systemic barrier imposed on marginalized scholars whose work challenges dominant academic norms. The research tax also manifests through structural exclusion, limited publication opportunities, and the emotional labour required to navigate biased systems. This paper is based on a research study that uses a critical discourse analysis (CDA) of Calls for Papers (CFPs). We detail our methods, selection criteria, and findings in later sections, but in this next section, we foreground how this analysis demonstrates that academic publications—especially in writing-focused fields—often perform commitments to diversity and equity while structurally withholding them, a contradiction especially visible in relation to feminist, decolonial, and transnational research. While our audit offers a structural analysis of CFPs, it is not neutral; it is shaped by our positionalities as researchers, which influences what we notice, what silences we register, and how we interpret exclusion.

Positionality

Waed Hasan: My Experience Searching for a Place in Academia

Reading these CFPs, I did not just analyze them. I scanned for signals: Would I be allowed to speak in my voice? Could I name Palestine? Would writing about refugee memory be seen as “relevant” or too “specific”? As a third-generation Palestinian refugee, an EAL speaker, and a woman with an invisible disability, my relationship to academic publishing is anything but neutral. I am always aware that I enter these spaces already read through a lens of difference or expected to represent the Palestinian diaspora. My work often focuses on refugee experience, Palestine, and BIPOC resistance, but in the context of most CFPs, that makes me a theme, not a scholar. These calls often tell me I am welcome, but only if I can fit my research and perspective into Western norms. Words like “global,” “equity,” or “community” do not register as open doors but as an invitation to assimilate into what is expected. I know this because I have done it. I have revised refugee narratives to sound less “political.” I have replaced “Palestine” with euphemisms. I have had colleagues warn me that naming settler colonialism might “limit my publication options.” This is the research tax. It is not just intellectual for me, it is emotional. It is the exhaustion of filtering my voice through expectations that were never made for me. What I am asked to “fit” into is not simply the language of global belonging but the assimilationist frameworks of Western scholarship, which consistently flatten refugee epistemologies into case studies rather than theories in their own right.

A concrete example of this tax appeared in the CFP for Global Crises Cultures: Representing Refugees in the 21st Century, where my chapter on refugee writing was accepted. Even though I was thankful for the opportunity to be heard, I experienced an increased sense of anxiety in deciding whether I should submit my work at all. The call referenced “refugee fictions, poetry, film, literary journalism, and life writing” but never named Palestine, settler colonialism, or Arab diasporas. Instead, it emphasized broad “global” contexts—Ukraine, Sudan, Venezuela—without acknowledging that some of the most protracted and structurally erased refugee conditions exist within these categories. Submitting to that volume required me to weigh every word: Should I say “Israeli occupation” or leave it unsaid? Should I quote BIPOC Palestinian writers who are rarely cited in academia, or stick to theorists already recognized in Western scholarship? Even in a collection about refugees, it felt like Palestine had to be smuggled in.

As a graduate student working to publish, I have had to rely on themed special issues because my area of interest, refugee poetics, is nearly impossible to locate within general CFPs. While my research insists that refugee writing must not be limited to a Western, humanitarian, or postcolonial lens, I find these are often the only frameworks general academic publications allow. Refugee work is made legible only when flattened. Similarly, when I read CFPs that reference “marginalized voices” but never name who they mean or cite such voices, I feel a double erasure: first, as a writer who is supposedly included, and second, as someone whose community is invisible even in the language of inclusion. I have never seen a general CFP that names Palestinian scholars or that invites refugee epistemologies as more than a case study. Even when refugee issues align with themes such as migration, precarity, and violence, they are not mentioned. And that omission speaks loudly.

Sarah Rewega: When Posing the Problem Made Me the Problem

What happens when your writing and research are met with silence? Like Waed, I found that doubt begins to creep in. You start to feel like you are potentially getting in the way or doing something wrong when your submissions are not acknowledged. For the past two years, I have been studying how feminist protest images, particularly from the MENA region, circulate online and generate conversations that push back against dominant narratives. My work explores how these digital spaces create room for voices that are often silenced or dismissed, and how images can become vessels for collective memory, resistance, and feminist solidarity.

But as I have tried to share this research through CFPs and submissions, I have often been met with silence. After sending follow-up after follow-up, with most disappearing into nothing, I walked into my mentor’s office, emotionally exhausted. She reminded me that feminism may have made its way into the academy, but not all forms of feminism are welcomed equally. In her experience, she had witnessed the disregard of feminisms that decenter Western contexts or that speak truths unsettling to dominant narratives. That moment reminded me of Sara Ahmed’s point in Living a Feminist Life: when you pose a problem, you then become the problem. In my case, the problem and I are inseparable: my research on transnational feminist protest is read as disruptive precisely because it refuses to center Western contexts, and so the critique attaches to me as much as to the work itself.

These refusals are not empty. As Cheryl Glenn reminds us, “rhetorical power is not limited to words alone, and for this reason, the study of silence has much to offer to the powerful and disempowered alike. Every rhetorical situation offers participants an opportunity to readjust or maintain relations of power” (23). The silence I encountered from journals was not absence but a rhetorical act, one that reinforced the boundaries of what kinds of feminism are welcomed into academic publishing. While this is one way the research tax has shaped my experience, thereby limiting my ability to speak openly about the injustices faced by women in the MENA region, what feels equally disheartening is the lack of special thematic issues that directly address these concerns. In my experience, CFPs on feminism and decoloniality tend to fall into two broad categories: (1) those centered on colonial violence and diasporic experiences, often with a broad or historical lens, and (2) those focused on Western feminist issues, primarily situated in the U.S. For instance, one CFP we audited focuses on body image and menstruation, framing it as “largely metaphorical and often downright shameful” (Call for Papers for a Special Issue of Peitho, Summer 2025). This is undeniably an important topic, and I do not mean to diminish its relevance. But the absence of thematic issues that center urgent feminist struggles outside of the West, like the safety and resistance of Iranian women protesting in the wake of Mahsa Amini’s death, raises important questions. Where do these stories belong? And what does it say about the boundaries of inclusion when there is no clear space for them?

This is another way that the research tax is imposed: waiting for journals to create space, bending and squeezing into frameworks that were not made for you. Themed issues, then, are double-edged: while they provide crucial and sometimes the only spaces where research like mine can be provisionally welcomed, they also risk confining marginalized scholarship to temporary “special” venues instead of integrating it into the ongoing core of disciplinary knowledge. Recognizing both their necessity and their limits is part of what it means to map the research tax.

Conceptual Framework

In the United States (U.S.) and across global academic contexts, DEI (diversity, equity and inclusion) initiatives are under sustained political and institutional assault. Recently, U.S. federal directives have sought to dismantle DEI policies across agencies and universities. For instance, a recent Reuters article explains that in January 2025, a new executive order directed federal agencies and contractors to remove outright ‘(DEI) policies’ not only in government agencies but also in private and academic sectors (Kimathi, 1). Meanwhile, new laws in states like Ohio and Florida have banned DEI offices, training sessions, DEI-linked hiring practices, and cultural centers. Despite being essential support spaces for marginalized students, they are now being shut down entirely (The Washington Post). In a time when it is imperative to keep DEI alive, this article turns to Sara Ahmed’s critique of performative diversity and Cedric Burrows’ articulation of the “Black tax” to theorize the additional intellectual, emotional, and institutional labour required of marginalized scholars navigating academic spaces under siege.

Building on their critiques and considering an intersectional feminist framework to further understand the labour and structural inequalities experienced by marginalized scholars, we develop the notion of the “research tax,” a conceptual lens that captures how this labour is extracted, making the very presence and critique of marginalized scholars burdensome. Intersectionality, first defined by Kimberlé Crenshaw, highlights how overlapping social categories such as race, gender, and class intersect to produce unique experiences of marginalization and oppression (Crenshaw). Similarly, in Living a Feminist Life, Sara Ahmed discusses what intersectionality means in application: “This is what intersectionality can mean in practice: being stopped because of how you can be seen in relation to some categories (not white, Aboriginal; not middle class)” (Ahmed 119). By framing the research tax within these perspectives, we show how marginalized scholars face compounded labour pressures when engaging with scholarly systems such as CFPs and institutional gatekeeping, which often prioritize dominant norms and voices.

In On Being Included: Racism and Diversity in Institutional Life, Sara Ahmed interrogates the term “diversity” through an ethnographic exploration of how it is used in academic institutions. She looks at what diversity does as a practice, showing how it is often used to protect and enhance an institution’s reputation rather than to address the inequalities it claims to remedy. Ahmed notes, “the shift to the language of diversity could thus be understood in market terms; diversity has a commercial value and can be used as a way not only of marketing the university but of making the university into a marketplace” (53). Ahmed asks, “What does diversity actually do?” and “What are we doing when we use the language of diversity?” This paper follows her line of thinking and borrows from her idea of diversity as performative to examine how diversity appears in CFPs.

Both what we are calling the “research tax” and Ahmed’s work on diversity share a central concern: institutions rely on marginalized people to represent and speak to structural inequalities while refusing to address the structural barriers that create them. This mirrors one of Cedric Burrows’ key arguments about the “Black tax,” which he defines as the extra labour African American graduate writers must perform to participate in white academic spaces. Burrows argues that one way the “Black tax” occurs is by expecting these marginalized groups to represent their race. He states that “when the African American pays the tax to enter white society, they will not be seen as a person. Instead, as a representative for the race, they hold the responsibility for speaking about issues that affect African Americans, for behaving in ways that are considered appropriate and non-threatening, and for being an outstanding student: in essence, they hold all the responsibilities of an ambassador charged with representing a sovereign nation” (Burrows).

Hence, borrowing from both Burrows and Ahmed, we propose the “research tax” as a way to theorize the ongoing institutional demands placed on marginalized graduate scholars, particularly those whose work critiques dominant academic norms (E.g., decolonizing practices). We aim to highlight how systemic inequalities shape which research is valued, recognized, or even allowed to enter scholarly conversations. While Burrows identifies how Black graduate writers are taxed to conform and represent within predominantly white institutions, and Ahmed explores how “diversity” work is both demanded of and contained by marginalized figures, the research tax builds on both concepts by naming a specific cost extracted through scholarly publication processes. In doing so, we draw attention to “institutional gatekeeping,” revealing how CFPs selectively legitimize certain research while burdening and ignoring those who challenge academic norms. The metaphor of a “tax” also points to the emotional and intellectual labour involved in navigating these academic spaces. As Ahmed notes, the labour of diversity work often falls on those whom the institution marginalizes. Similarly, the research tax demands an extra level of emotional resilience, interpretive self-censorship, and rhetorical adaptation simply to have their work considered. This paper, then, offers a conceptual and experiential account of how academic institutions perform commitments to diversity and equity while structurally ignoring the inequalities, particularly concerning feminist, decolonial, and transnational research.

Methods

In this paper, we employ a critical discourse analysis (CDA) that bridges our lived experiences of navigating academic publication and the research tax through the audit and close reading of seven CFPs, including feminist, decolonial, writing center, and transnational writing studies journals. We use this method to trace how inclusion is constructed in CFPs and how language contributes to the research tax experienced by marginalized writers or writers centring marginalized research. We frame this audit as a counter-hegemony practice. As Laurie Adkin defines it, “counter-hegemony refers to the efforts of social and political actors that challenge the cultural and institutional foundations of hegemony. They call into question the structures, beliefs and norms that underline the economic, social, and political order, and attempt to show that alternatives to the status quo exist, are needed, and are achievable” (Adkin). This framing emphasizes that our work is not neutral, but a critical and political intervention into how publishing structures shape knowledge, access, and legitimacy.

We use CDA to examine how CFPs structure normativity and legitimacy through language. CDA helps reveal how institutional power is embedded in genre, tone, and rhetorical framing, not just in what is said, but how it is said. In Language and Power, Norman Fairclough notes, “What comes to be common sense is... determined by who exercises power and domination in a society or social institution” (113). This framing allows us to trace how certain scholarly voices are constructed as standard, while others, particularly feminist, refugee, or Global South epistemologies, are marked as marginal or exceptional. CFPs, we argue, operate as gatekeeping texts, shaping the very conditions of who is publishable. Our audit method uncovers the disconnect between performative inclusion and material support. Finally, it provides the groundwork for our analysis of topic exclusion, authorial barriers, and the research tax.

CFPs are not passive documents; they are manifestations of institutional power that reflect and enforce expectations about who is allowed to publish and on what terms. Fairclough explains that “Having the power to determine... which linguistic and communicative norms are legitimate... is an important aspect of social and ideological power” (110–11). As direct reflections of institutional demands and expectations, CFPs do not simply invite submissions; they communicate whose knowledge “fits” and whose does not. This power often appears neutral or inclusive, but as Fairclough indicates, it operates through “hidden power” that produces an “unequal social distribution of access” to language and discourse itself (83). While Fairclough grounds this analysis in CDA, we extend his framework by foregrounding our positionality as scholars who directly navigate these exclusions. Our subjectivity is not separate from CDA but an essential component of how we interpret the “hidden power” encoded in CFPs. In this way, our CDA is strengthened by making explicit how our standpoint shapes our interpretation. Our audit aims to expose these patterns of how diversity is used performatively, while structural support remains absent.

We conducted a critical audit of seven CFPs (2023–2026), each from a different venue: The Journal of Multimodal Rhetorics (“Composing at the Intersections: Queer, Transgender, and Feminist Approaches to Multimodal Rhetorics”); Peitho (“Girlhood and Menstruation”); MENA Writing Studies Journal (Inaugural issue, “On Our Own Terms: Engaging Conversations about Writing Studies in the Middle East and North Africa”); Peitho – Cluster Conversation (“(Re)Writing our Histories, (Re)Building Feminist Worlds: Working Toward Hope in the Archives”); CWCA/ACCR 2025 conference CFP (“Precarity and Agency in Writing Centres”); WLN Digital Edited Collection (“The Future of Writing Centers”); and ECWCA Journal 2026 issue (“Connections & Conversations: Building and Sustaining Community in Writing Centers”). In addition to these special issues and themed CFPs, we also reviewed the standing “Submit” sections and regular submission guidelines of each journal. This comparative step allowed us to see whether inclusionary language and equity gestures were unique to special calls or reflected in ongoing publishing policies.

These CFPs came from issues or collections in feminist, decolonial, writing center, and transnational writing studies journals. Each was chosen because of its stated investment in diversity, intersectionality, or transformation, making them ideal sites to examine how institutional gatekeeping persists even within “inclusive” spaces. For instance, the Journal of Multimodal Rhetorics framed its issue as one that sought to “engage intersectional multimodal composing as actionable and disruptive practices to the material and ideological structures of heterosexist, white supremacist systems.” Similarly, Peitho’s call for its Girlhood and Menstruation issue argued that “feminist scholarship like that found in Peitho, focusing on subjectivities that are often marginalized and ignored via traditional and non-traditional texts, is the perfect place to take lived menstruation experiences seriously (Call for Papers for a Special Issue of Peitho, Summer 2025).” Meanwhile, the inaugural issue of the MENA Writing Studies Journal made clear its intent to “push against the parachuting of methods while championing local, individual approaches to terminology and praxis (MENA Writing Studies Journal).” Finally, the Cluster Conversation on Feminist Archives grounded its call in an explicitly intersectional and justice-oriented frame, explaining that “overlapping forms of oppression require a rigorously intersectional framework for cultivating hope (Cluster Conversation on Feminist Archives).” As the audit findings will show, these excerpts illustrate the ways calls deploy the language of inclusion and transformation to attract submissions, while also revealing how inclusion is often structured within narrow or U.S.-centric logics. This audit highlights the discrepancy between what CFPs claim to welcome thematically and what they structurally enable, revealing how gestures toward inclusion often mask enduring exclusions in authorship, access, and epistemic legitimacy.

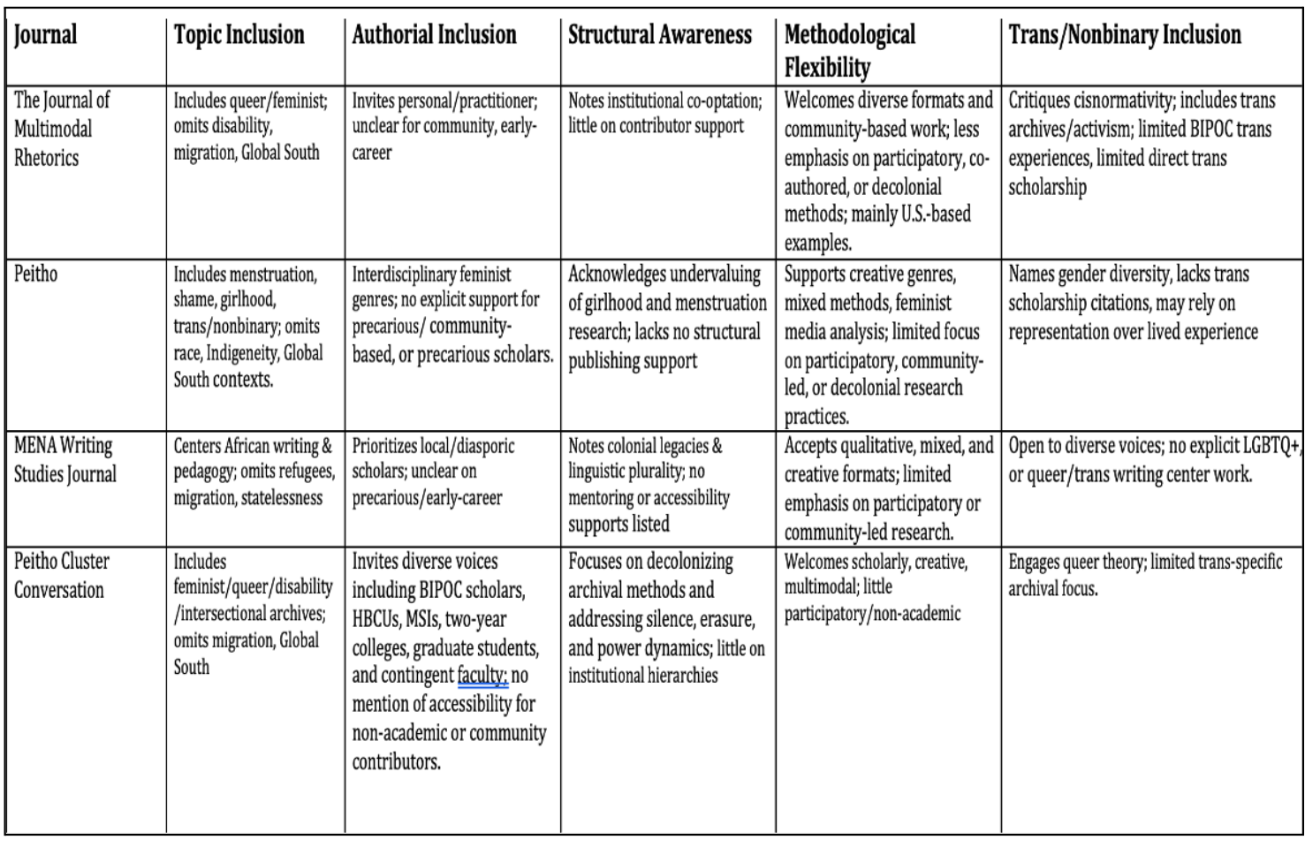

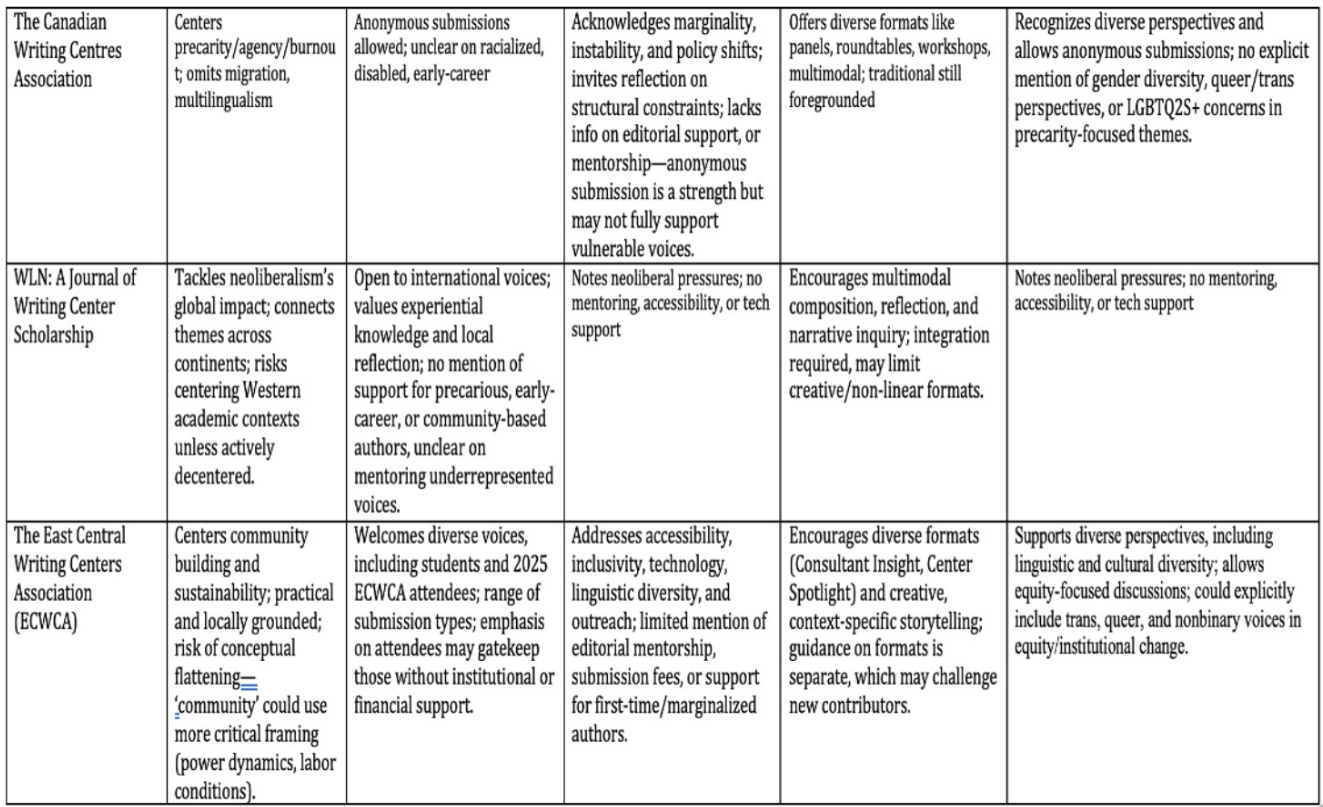

Using a CDA, we coded each CFP across five categories: topic inclusion, authorial inclusion, structural awareness, methodological flexibility, and trans/nonbinary inclusion. These categories emerged inductively as recurring sites where CFPs signal (or fail to signal) commitments to equity. Moreover, we identified these particular categories based on our own experiences navigating academic publishing from marginalized positions, which sensitized us to patterns of inclusion and exclusion in the CFPs. By “topic inclusion,” we refer to whether the CFP thematically engages marginalized or global perspectives beyond dominant U.S. contexts. “Authorial inclusion” captures whether calls explicitly invite contributions from precarious, early-career, community-based, or non-institutionalized writers. “Structural awareness” identifies if a CFP acknowledges the material barriers of publishing—such as access, mentoring, or editorial support. “Methodological flexibility” considers whether the CFP makes space for diverse or nontraditional research genres, creative modes, or participatory/community-led practices. Finally, “trans/nonbinary inclusion” codes for explicit recognition of gender diversity and trans or nonbinary scholarship, moving beyond generic references to ‘diversity’ or ‘LGBTQ+.’ Meeting these standards meant that a CFP directly named or provided support for these forms of inclusion, rather than assuming them implicitly.

Audit Findings

While all the CFPs selected use inclusive language—for example, the MENA Writing Studies Journal frames its call around “terms that are clearly originating from the needs and concerns of this social, cultural, and political context”—and appear inviting to all writers, they ultimately reproduce structural barriers under the guise of openness (MENA Writing Studies Journal). They perform the rhetoric of an aesthetics of diversity while preserving systems of exclusion. Ahmed uses the concept of the “non-performative” to explain how institutional speech acts “name” but “[do] not bring into effect” the very things they name. She writes, “the failure of the speech act to do what it says is not a failure of intent or even circumstance but is actually what the speech act is doing” (Ahmed 117). Institutions can use inclusive language while enacting the opposite by performing diversity in language while maintaining exclusion in practice. This disjunction between what is said and done is central to how CFPs work.

One area we focused on is topic inclusion gaps. Even though the selected CFPs use inclusive language like “global,” “community,” and “precarity,” they all fail to mention refugees, the Global South, and decolonial frameworks in explicit or sustained ways. These broad categories may appear open-ended, but they are not neutral: they often signal U.S.-centric or Western academic frameworks rather than making space for specific epistemologies. For instance, when “global” is used without naming refugee conditions or Global South contexts, it functions as an abstraction that assimilates difference into dominant terms rather than centring marginalized realities. Similarly, “community” tends to presume institutional or national communities, while “precarity” is framed largely in relation to academic labour in the West, leaving migrant or stateless precarity unnamed. As summarized in Table 1 (see Appendix), the degrees of inclusion and omission vary across CFPs, with some offering gestural references but none providing sustained engagement. In terms of the writing centre CFPs, five out of five completely exclude migration or non-Western scholarship and methodologies. One CFP, for example, uses “intersectional multimodal composing” without addressing displacement, diaspora, or colonial legacies. Even the MENA Writing Studies CFP, while regionally focused, does not include mention of refugees or diasporic communities, despite claiming to reject limited Western pedagogies. Similarly, writing center CFPs do not engage in refugee literacy, migration, or postcolonial realities even when focusing on labour, precarity, or equity.

There are two key ideas to take into consideration. First, publications cannot assume that all writers, especially marginalized writers, will feel welcome to share their work, particularly if addressing controversial political topics. These exclusions, or abstract gestures like “global,” produce a form of epistemic research tax. For instance, Ahmed indicates that people of colour “embody diversity by providing an institution of whiteness with colour” (4). However, this embodiment is a burden because the institution gives people of colour the job of diversity while remaining systematically unchanged. Marginalized authors often feel like they must reshape their work into recognizable/acceptable Western frameworks to be legible. This process may involve muting cultural specificity, softening political critique, or adopting disciplinary norms that erase lived context. As Sara Ahmed reminds us in Living a Feminist Life, citation itself is a feminist and political practice: “Citation is how we acknowledge our debt to those who came before; those who helped us find our way when the way was obscured because we deviated from the paths we were told to follow” (15). When CFPs overwhelmingly cite U.S.-based scholars, they implicitly discipline contributors into reproducing those same frameworks rather than citing Global South, Indigenous, or refugee scholars. For example, Palestinian writers such as Ghassan Kanafani or refugee theorists like Edward Said remain largely absent, even when CFP themes align with their work.

This absence is not only about citation but also about what kinds of authorial voices are positioned as legitimate, which links directly to questions of “authorial inclusion.” For example, the multimodal rhetoric CFP asks for “intersectional” and “community-led” work but centers U.S. activist contexts and cites primarily American scholars, effectively requiring non-U.S. contributors to translate their work into that framework. While it is true that some research can productively fit within those frameworks, and doing so is not inherently harmful, the research tax lies in the disproportionate labour marginalized scholars must perform to make their work legible within them, rather than being welcomed on their own terms. For instance, work on intersectionality by scholars such as Chandra Talpade Mohanty or on community-led rhetorical traditions by decolonial thinkers like Linda Tuhiwai Smith could have been acknowledged, but instead the call draws almost exclusively from U.S. activist and academic contexts. To engage intersectional and community-led work more equitably, CFPs and the scholars responding to them must cite a wider range of voices. In turn, doing so helps avoid the further marginalization or erasure of previously silenced perspectives. We therefore treat citation politics as part of authorial inclusion, since whose work is cited both signals which authors are invited into the conversation and shapes whose epistemic authority is recognized as legitimate.

Second, the lack of specificity assumes a type of assimilation and universalization that ignores structural and geopolitical differences. For example, the Multimodal Rhetorics CFP calls for “intersectional” and “community-led” work but illustrates these terms almost exclusively through U.S. activist contexts, such as the Combahee River Collective or chalk-walk demonstrations. By framing intersectionality through American histories while omitting refugee realities or Global South epistemologies, the CFP positions contributors from outside the U.S. as needing to translate their work into U.S.-centric frameworks in order to be legible. In this way, CFPs reproduce colonial logics of inclusion: welcoming “diverse” voices only if they conform to fit dominant norms. Ahmed describes the emotional labour this entails as “banging your head against a brick wall” (175). She elaborates, “The feeling of doing diversity work is the feeling of coming up against something that does not move, something solid and tangible” (26). This example highlights how the rhetoric of inclusion operates as assimilation: marginalized scholars are invited in only if they adapt their knowledge to dominant categories. This metaphor captures how institutional resistance comes at an emotional and material cost. Even as marginalized scholars try to engage in academia, their contributions are limited by the boundaries of what kinds of knowledge and critique institutions are willing to absorb without internal change.

Topics that deal with feminist, transnational work, the Global South, and migration are relegated to special issues and themed calls. This pattern was central to our analysis: all of the CFPs we reviewed were drawn from such special issues, which signals both the field’s recognition of these topics and its tendency to segregate them. While these issues do allow for visibility, they also function as containment zones, offering temporary platforms while keeping essential marginalized voices and experiences outside the spectrum of the field. In this sense, special issues are double-edged: they bring much-needed attention to underrepresented areas, but they also mark them as exceptional rather than central. As Ahmed writes, “Diversity can allow organizations to retain their good idea of themselves,” even if they continue to affirm inequalities beneath the surface (71). Institutions showcase conditional moments of inclusion as proof of progress while keeping structural norms intact. Thus, special issues are not simply “good” or “bad.” They are valuable in spotlighting overlooked concerns, but they risk reifying the very marginalization they aim to disrupt by placing feminist, transnational, and Global South scholarship inside categories rather than within the field’s ongoing core conversations.

This trend is particularly gendered: feminist and trans or queer scholarship is welcomed only within narrow thematic confines but not treated as foundational or field-shaping. For instance, the Peitho CFP on Girlhood and Menstruation reflects a form of white feminism: it situates menstruation primarily as a metaphorical and cultural concern of (implicitly Western) girlhood, while failing to engage the material realities of reproductive justice, refugee health, or Global South perspectives. Likewise, the MENA Writing Studies Journal CFP frames itself as resisting “parachuted” Western methods and emphasizing local terms and praxis, yet it does not name refugee, migrant, or stateless populations that are central to the region’s realities. This pattern suggests that feminist and queer scholarship is positioned as valuable only when tied to a special theme, rather than integrated into the ongoing methodological and theoretical core of the field. This is another form of institutional research tax where the labour of producing radical or situated scholarship is acknowledged only thematically and on editorial terms.

To assess how academic publications approach marginalization, we had to review a majority of special issues. On one hand, this can be read as editors realizing the need to encourage scholarship in areas that are not typically forthcoming. Special issues also collect different perspectives on a topic in one place, enhancing the visibility of authors whose work might otherwise go unnoticed. Yet, none of the CFPs suggests that this work belongs in the general or ongoing issues of the journals. The Peitho CFP on girlhood and menstruation, for example, explicitly frames its topic as a “special issue,” despite exploring foundational questions of bodily regulation and trans inclusion, effectively signalling that such work is not part of the core journal's mission. This limitation to special issues sends a clear message that certain pieces of knowledge are exceptional, but not foundational.

Similarly, CFPs perform inclusion without offering structural support. This approach to publication assumes equal access and reinforces barriers for precarious, early-career, graduate, differently-abled, and marginalized scholars. Ahmed calls this “diversity work.” She argues that “diversity work is hard because it can involve doing within institutions what would not otherwise be done by them” (Ahmed 25). In terms of the non writing center CFPs, none mention mentorship and accessibility accommodations directly. Some CFPs accept multimodal work but do not explain how less-resourced authors can access tools or navigate the review process. Following the categories outlined in our methods section, we coded this gap under “structural support” rather than “methodological flexibility.” While “methodological flexibility” indicates that journals are open to diverse genres, “structural support” refers to whether they provide the resources (such as guidance, mentorship, or technical access) that make such submissions possible. Without that support, the invitation to multimodality risks being more symbolic than substantive. WLN’s digital edition calls for multimodal submissions but provides no information on technical support or assistance, placing the burden on contributors to figure out format, tools, and platforms. While this gap reflects a lack of structural support for contributors, it also raises questions of labour justice: to what extent can journals—often operating on volunteer editorial labour within an underfunded higher education system—realistically provide such resources? This tension highlights how the politics of inclusion in CFPs are intertwined with broader labour crises in academia, where both contributors and editors are asked to do “diversity work” without adequate institutional backing.

Alternatively, writing center CFPs show some effort in the structural support area but still show evidence of structural exclusion. For instance, the CWCA CFP allows for anonymous submissions, which can reduce vulnerability for precarious or early-career scholars. However, it does not explicitly address how refugee or racialized scholars—who face additional barriers—might be supported. WLN, in its call for multimodal submissions, assumes contributors have technological access and skills, yet it provides no accompanying guidance, training opportunities, or resource-sharing to ensure less-resourced authors can fully participate. Similarly, ECWCA relies on conference participation, effectively excluding Global South authors and students without funding. Even when CFPs like ECWCA’s encourage “community engagement,” they frame community primarily through writing center stakeholders such as students, staff, faculty, and local organizations. This emphasis on local, campus-based, and regional partnerships reflects a U.S.-centric scope and does not address how international or Global South scholars might participate. While the CFP briefly acknowledges multilingual and international students, it does so within the framework of U.S. writing centers rather than expanding community to include non-Western institutions or authors. In this way, calls for “community engagement” reproduce structural exclusion by centring Western-based institutional relationships. This reflects how structural exclusion operates not just through what is said, but what is omitted: the logistics of access. The lack of logistics, such as language access, makes inclusion symbolic. It effectively says, “You are welcome to submit, so long as you need no help to get here.” These gaps impose institutional and affective burdens on contributors to bridge the divide on their own.

Even at the level of language, CFPs use inclusion performatively while requiring marginalized scholars to do additional interpretive, linguistic, and emotional labour. Four out of five of the general CFPs invoke progressive terms like “equity” or “intersectionality” without clarifying how these values shape review criteria or editorial decisions (a problem of structural support). This vagueness places the burden of interpretation on authors, who must anticipate what counts as “appropriate” within unstated institutional norms. In this sense, progressive language functions less as a guarantee of equity and more as a way of preserving editorial authority without redistribution.

Additionally, the CFPs’ lack of explicit accessibility accommodations underscores how inclusion remains rhetorical rather than structural. For example, writing center CFPs frequently highlight “community” and “diversity” but offer no framework for supporting multilingual or refugee scholars — whether through translation, mentorship, or alternate submission formats. This gap belongs squarely in the category of accessibility, since it reflects the absence of proactive accommodations. None of the CFPs mention translation, language diversity policies, or support for non-native English speakers. To ensure these absences were not merely omissions in the CFPs, we also reviewed the submission guidelines on each journal’s website. Across those sections as well, we found no provisions for multilingual submission, translation, or accommodations for authors working in languages other than standardized English. Even journals that emphasize “inclusive pedagogy” in their thematic framing assume fluency in English and offer no alternative formats. In this way, linguistic and infrastructural labour is offloaded onto the contributor, while institutions retain the appearance of equity.

Recommendations

Our audit and lived experiences reveal that inclusion in academic publishing is often symbolic, but rarely supported structurally. To ease the research tax, we must move from symbolic inclusion to systemic change. Some journals have adopted important practices in this direction. For example, The Peer Review has adopted anti-racist reviewer approaches, and long-standing feminist journals such as Feminist Studies, Hypatia, and Women’s Studies Quarterly have created space for intersectional and transnational feminist work. While these journals were not part of our dataset, we reference them here to demonstrate that alternative publishing practices are both possible and already underway. These efforts matter, but they remain the exception. Our recommendations build on these models while arguing that such practices must be normalized across the publishing landscape, rather than confined to explicitly progressive journals or special issues.

First, we must diversify editorial boards; not because of how it looks, but because everyone deserves to be represented and understood. Calls for diversity must move beyond symbolic gestures. It is not enough to include “women” or “international scholars” in name only. Editorial boards must reflect the epistemologies they claim to welcome. Journals like The Peer Review and Feminist Studies offer initial models, but even these must expand to include trans scholars, Black and Indigenous thinkers, and refugee or stateless writers from the Global South. Without meaningful inclusion of those directly impacted by structural exclusions, editorial boards risk reproducing the very barriers they claim to dismantle.

Second, academic publications should increase transparency in publishing metrics. We propose that academic journals regularly publish transparent data on submissions, acceptances, reviewer demographics, and reasons for rejection, broken down by race, gender, region, language, and methodology. Such transparency would make visible the systemic exclusions currently hidden behind invisible editorial processes. It would also provide a baseline for accountability, helping to track progress (or lack thereof) in diversifying publication practices. Moreover, there should be public accountability for equity statements. If a journal claims to be “committed to diversity,” we ask: how, and how often, is that commitment evaluated? We recommend that journals publish annual or biennial reports showing how equity and anti-racist policies are enacted and assessed. This should include concrete changes in editorial practices, reviewer recruitment, and support for non-normative methodologies, not just statements of good intention. Without assessment, “diversity” remains an institutional performance, not a practice. Moreover, this invites journals to move beyond symbolic commitments by embedding anti-racist practices throughout their publishing structures. Building on Cedric Burrows’ call for structural reform, we argue that journals must explicitly define what counts as racialized bias (e.g., demanding “neutrality” from refugee scholars, or questioning the “relevance” of feminist and decolonial frameworks). These standards should not remain abstract commitments; they must be embedded in the very processes that determine what research is considered “fit to publish.”

In addition, we advocate for journals to actively encourage and prioritize collective or co-authored submissions. We recognize, however, that institutional reward structures often devalue collaborative work, privileging single-authored articles even though collaboration can involve more labour. Precisely because of these institutional constraints, journal practices can intervene by affirming relational, community-based knowledge production as legitimate and valued. Encouraging collaboration through flexible submission guidelines and clear policies for shared authorship credit would begin to shift publishing norms, even if academic evaluation structures lag behind. We also acknowledge that some journals in writing studies and writing centre studies have offered pre-submission workshops or mentoring sessions at conferences. While these are valuable, they remain insufficient, since conference participation often requires significant financial resources that many precarious or marginalized scholars cannot access. Expanding these initiatives into accessible, online mentorship programs—including peer-review workshops, feedback literacy training, and editorial coaching—would allow journals to support authors equitably. This proposal draws from and extends Burrows’ call for equity-building interventions across the publishing pipeline.

Importantly, journals should be cautious not to limit refugee, feminist, and transnational scholarship to special issues alone. While themed volumes are vital for visibility, they can also risk functioning as containment strategies if general calls do not make space for such work. Instead, general CFPs must explicitly name the epistemologies they seek to include—refugee theory, trans or queer critique, Indigenous frameworks, decolonial methods, and translation. Vague references to “diverse voices,” such as the CWCA CFP’s invitation that “welcomes proposals [...] related topics through diverse perspectives and methodologies,” place the burden on the author to self-identify as marginal while leaving epistemological frameworks unnamed. Naming is not exclusionary; it is what genuine inclusion requires.

Finally, we again acknowledge the increasing legislative attacks on DEI in parts of North America. However, even within restrictions, there are possibilities. Journals might relocate certain equity initiatives under “ethics” or partner with international institutions for review processes. Where possible, they can publish anonymized reflection pieces from authors experiencing structural exclusion, creating space for testimony when policy language fails. In short, resistance must be both imaginative and strategic. Underlying all these proposals is a belief that journals can be restructured not simply to include marginalized scholarship, but to be shaped by it. This shift requires more than invitations; it demands that institutions ask what conditions are required for publishing to be possible. Inclusion is not just about who is let in, but who shapes the room. Until refugee and Global South scholars are present in decision-making, not only as contributors but as editors and reviewers, inclusion will remain aspirational. The time for symbolic gestures is over; structural change is not only possible, it is overdue.

At a moment when DEI initiatives are under escalating pressure, this project’s urgency becomes even clearer. Naming and challenging the research tax is not just a diagnosis of existing inequities but a vital act of institutional and collective defense. By sharing our lived experiences, we hope others, too, might feel emboldened to resist and speak truth to power—because when journals and institutions commit to tangible, accountable actions that center marginalized voices in decision-making and editorial processes, the research tax rebate begins.

Works Cited

“Anti DEI Efforts Shutter Cultural Centres That College Students Call Lifelines.” The Washington Post, 14 Aug. 2025, https://www.washingtonpost.com/education/2025/08/14/multicultural-centers-universities-closing/.

Adkin, Laurie. “Hegemony & Counter-Hegemony.” Showing Theory to Know Theory: Understanding Social Science Concepts through Illustrative Vignettes, edited by P. Ballamingie and D. Szanto, Showing Theory Press, 2022. Ecumenical Campus Press. https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/showingtheory/chapter/hegemony-and-counter-hegemony/.

Ahmed, Sara. Living a Feminist Life. Duke University Press, 2017.

Ahmed, Sara. On Being Included: Racism and Diversity in Institutional Life. Duke University Press, 2012.

Burrows, Cedric. “Writing While Black: The Black Tax on African American Graduate Writers.” Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, vol. 14, no. 1, 2016.

Crenshaw, Kimberle, and Anne Phillips. “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory, and Antiracist Politics.” Feminism And Politics, Oxford University Press, 1998.

Ettorre, Elizabeth. Autoethnography as Feminist Method: Sensitising the Feminist “I.” Routledge, 2017.

Fairclough, Norman. In Language and Power. 2nd ed., Longman, 2001.

Glenn, Cheryl. Unspoken: A Rhetoric of Silence. Southern Illinois University Press, 2004.

Kimathi, Sharon. “Sustainable Switch: Challenges to Trump’s War on Diversity.” Reuters, 13 Aug. 2025

Lockett, Alexandria. “Why I Call It the Academic Ghetto: A Critical Examination of Race, Place, and Writing Centers.” Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, vol. 16, no. 2, 2019.

Appendix

Table 1

Comparison table of four journals—The Journal of Multimodal Rhetorics, Peitho, MENAWriting Studies Journal, and Peitho Cluster Conversation—across five categories: topic inclusion, authorial inclusion, structural awareness, methodological flexibility, and trans/nonbinary inclusion. The table summarizes how each journal includes or omits areas such as disability, migration, precarious scholars, decolonial methods, and trans perspectives, noting recurring limits like lack of structural support and reliance on symbolic diversity.

Table 2

Comparison table of three journals—The Canadian Writing Centres Association, WLN: A Journal of Writing Center Scholarship, and The East Central Writing Centers Association (ECWCA)—evaluating five categories: topic inclusion, authorial inclusion, structural awareness, methodological flexibility, and trans/nonbinary inclusion. Each cell lists strengths and omissions, highlighting gaps such as lack of mentoring, limited support for marginalized voices, and insufficient attention to queer/trans perspectives.