Praxis: A Writing Center Journal • Vol. 23, No. 2 (2026)

Mentoring in Editorial Spaces: Graduate Co-Editors as Literacy Brokers

Rabail Qayyum

University of Houston

rqayyum@hawaii.edu

Abstract

As a graduate co-editor of a writing center journal, I worked with two graduates Brenna and Erin (pseudonyms) who were trying to get their manuscripts published. While the former journey was successfully completed, the latter was not. In this study, I explore these journeys individually through textual analysis of manuscript drafts, reviewer feedback documents, email correspondence, notes from authors and reviewers for the editorial board, and my own meeting notes to make sense of the eventual outcomes. My study explicates how graduate co-editors mediate texts using literacy brokering as a conceptual framework, delineating my approach and process to mentoring, what graduate co-editors can offer to writers, and what recommendations can be drawn from Brenna’s and Erin’s examples for other editors, reviewers, and novice scholars. In this way, the study adds to scholarship on editorship in writing center journals by displaying what role graduate student editorial mentoring can play in creating ongoing opportunities for emerging scholars in navigating academic publishing after finishing graduate studies.

Mentoring Writing Center Scholars in Academic Publishing

Publishing can be a tension-riddled process, especially for first-time authors. What opportunities can help them navigate this process? According to a recent survey, 38% of recent graduates from Ph.D. programs in rhetoric and composition and related fields reported receiving very little or no guidance on scholarly publication (Ives & Spitzer, 2023). Even for the 60% of graduates who did receive mentorship in academic publishing during their doctoral programs, ongoing mentorship from the field could be helpful. The fact is that writing center studies is a niche specialization, and most scholars, regardless of specialty, continue to learn about publishing long after graduate school has ended.

Editorial mentorship can be one way to help novice scholars navigate academic publishing. The Peer Review (TPR) journal is endeavoring to make academic publishing more accessible by offering explicit remote mentorship from the editorial staff, a practice other journals in the field (e.g., WLN: A Journal of Writing Center Scholarship) have also adopted. Instead of gatekeeping, the emphasis on mentoring can create a pipeline for emerging scholars by providing support as they learn publishing skills. In addition to the professional editor and managing editor, TPR also includes graduate co-editors—an uncommon feature designed to professionalize these students as future writing center professionals. As a result, apart from typical job responsibilities like exercising autonomy in carrying out decisions made with the editorial team, corresponding with authors and reviewers throughout the publication process, and ensuring both internal and external blind peer review to uphold the integrity of the journal, graduate co-editors also have the unique responsibility of holding virtual mentorship meetings with authors to offer feedback and coaching as necessary.

To date, the field has not fully explored the role of editor—graduate or professional—in writing center journals. In Behind the Curtain of Scholarly Publishing: Editors in Writing Studies, Spooner et al. (2022) break new ground on the subject of editors’ roles, offering useful advice for editors to understand this important role in shaping the discipline and how to successfully enter into publishing in the discipline. However, none of the chapters included in their collection were written from a student editor vantage point. Likewise, although journals such as Writing Center Journal and WLN provide commentary about their editorial process, neither journal regularly staffs student editors, meaning that the student editor perspective is missing from scholarly conversations on writing center publishing.

Sheffield (2014) offers a useful discussion on the professionalization of graduate student editors, reporting the results of a survey of 13 graduate student editors at Rhetoric Review and exploring what the graduate editors had gained from the role. These gains were the result of fulfilling responsibilities such as copyediting, formatting, updating databases, and serving as liaisons between the journal and the authors. However, mentoring of novice scholars was not included in this list. Some explanation about this aspect of the editorial work is provided by Banville (2020) and Hashlamon (2020), former graduate co-editors at TPR. Their reflective pieces provide their personal motivations related to this role and reaffirm serving their own scholarly agenda of amplifying underrepresented and marginalized voices through this role. Hashlamon (2020) in particular mentions working “with writers struggling to carve out space for themselves within writing center studies” and “mediating reviewer-author interactions.” But more information is needed to understand exactly what this mediation is, and how it can support novice scholars in academic publishing.

TPR’s Process for Graduate Editorial Mentorship

Authors who receive mentorship from graduate co-editors at TPR are usually (under)graduate students with little to no experience with publishing. Sometimes it is the authors who seek out this mentorship by reaching out to the editorial board; other times it is the professional editor who, upon initial review of a submission, feels the manuscript needs additional work before it goes out for external review. In general, those seeking mentorship are first-time authors whose manuscripts require major revisions. In these cases, the support of graduate co-editors is called upon to field questions from the authors about revision (“So how do I revise this?”) and publication timeline (“So what happens next?”). Unfamiliarity with the publication process is one of the main challenges for novice scholars (Arsenault et al., 2021; Fazel, 2019), and graduate editors can help demystify this process.

Mentoring typically happens at two stages: first, before a manuscript has gone out for review; and second, after a manuscript has received (at least) one round of review. The process unfolds as follows:

I receive an email from the professional editor linking me with the author.

I send the author an email letting them know my availability for a virtual meeting. I also ask them to share any revised work in the form of MS Word document, with questions or comments in the margin using the Comment feature.

If I receive any preliminary revised work, I read through it and add my comments to it, while also responding to the author’s questions or observations.

I take meeting notes (I use the Notepad application), writing down the major points the author needs to address. I also read through the reviewers’ feedback (if available) and revise my comments and notes in light of their feedback.

I meet with the authors virtually.

Post-meeting, I share my written feedback with the authors.

In virtual meetings, which usually last an hour, we discuss any of the reviewer feedback that is troubling the authors, discuss ways to incorporate feedback, and negotiate the submission deadline. I begin by asking authors about their background (“Where do you study/work?”). I then direct them to relevant readings as either examples to obtain ideas from in terms of structure or as evidence to cite. I show them, using Zoom’s screen sharing feature, my own way of incorporating reviewer feedback to serve as one model of synthesizing feedback. I go over TPR’s guidelines for authors to navigate this complex stage.

Literacy Brokering as a Framework for Understanding Graduate Editorial Mentorship

Lillis and Curry (2006) employ the term “literacy brokers” (p. 13) for editors, reviewers, academic peers, and others “who mediate text production in a number of ways” (p. 4). Therefore, the term literacy brokering situates mentoring in the context of textual changes and the author-literacy broker relationships. To differentiate between mentoring and mediating in this paper, following Orland-Barak (2014), mentoring is understood to mean mediation of professional learning, and is hence a much broader concept, whereas mediating is used in the sense of textual changes. Lillis and Curry’s (2006) approach encompassed two aspects: one, “observing the ways in which scholars gain access to brokers and the subsequent impact of brokers on text production,” and two, “theorizing the relations between brokering and authoring activity in relation to publication” (p. 13). They acknowledge the inequities and power dynamics at work within this kind of editorial mentorship:

We acknowledge that the mediation of academic texts is not a neutral enterprise but rather involves participants of unequal status and power: In many instances, literacy brokers occupy a powerful position straddling the “boundaries and peripheries” (Wenger, 1998, p. 199) between various communities, influencing opportunities for publication. (p. 13)

In other words, the editor puts their mediation into circulation by adding value to the author’s work, which has inherent inequities of power dynamics. Nevertheless, Lillis and Curry’s (2006) text-oriented, longitudinal, and ethnographic study is useful because it illustrates in broad terms the nature and extent of literacy brokering in English-medium publications and characterizes and exemplifies brokers’ different orientations. Their study is relevant to mine because I too explore the graduate co-editor’s (a type of literacy broker) role through changes across drafts. Their study helps frame graduate editors’ mentoring roles not in terms of perceptions or abstract understandings but in terms of concrete changes made to drafts. Lillis and Curry (2006) devised a heuristic listing 11 kinds of these changes, which include additions, deletions, reformulations, reshufflings, argument and positioning development, lexical or register changes, sentence-level changes or corrections, cohesion markers, publishing conventions, and visual or representation of text.

All in all, the general purpose of the literacy brokering framework is to make the various forms of changes made by different stakeholders more explicitly noticeable. The framework specifically lists editors as literacy brokers and is inherently well equipped to discover trends in mechanisms behind developing manuscript content and generating knowledge.

In the next section, I explore the impact of a graduate co-editor in the production of texts written for publication, looking specifically at the trajectories of two recent examples as case studies. These contrasting examples will shed light on the roles graduate co-editors can play and the degrees of their effectiveness, authority, and agency in the publication process. I chose these two case studies because they were comparatively recent and allowed a richer analysis with the purpose of finding deeper meanings.

At this point, I would like to offer some contextual information about my background and my positioning with respect to the authors featured in the following case studies, Brenna and Erin. I am an international doctoral student in the U.S. in second language studies. When I started writing this paper, I had worked as a graduate co-editor for over two years and had mentored authors on four different manuscripts. I had a few publications under my belt when I started this job, and in the course of working at this job, I published one research paper in a prestigious journal of my field. On the other hand, Brenna and Erin were both recent Master’s graduates. Brenna was the assistant director of a writing center at a public research university in the U.S., while Erin was a tutoring coordinator at a large public university also in the U.S.

I would clarify here that my use of successful and unsuccessful labels to describe these cases is merely for their publication trajectories and is not meant as a comment on the efficacy of mentoring. I do not view successful mediation simply as getting a manuscript published nor failure as being unable to achieve this outcome. Publishing a manuscript is certainly an important outcome, but successful mentoring, I feel, can incorporate a host of other benefits like understanding publishing norms, increasing confidence, developing a more accurate understanding of strengths and weaknesses as a writer, engendering a desire to publish again, among others.

The Case of Successful Mediation: Brenna’s Example

The editorial team received an email from our managing editor asking for their thoughts on a proposal for a piece. The proposal was a 192-word paragraph about how writing centers can better support a distinct student demographic, focusing on their disciplinary identity. I found the proposal interesting and wrote back to the team that I deemed the piece “useful.” I noted that our journal had published papers in the past related to the topic but those took a broader perspective; therefore, it will “be interesting to see how this one differs and what unique resources the author can pinpoint.” In response, the professional editor assigned the manuscript to me to work with the prospective author. She also recommended a direction for the piece, observing that the proposal included almost no references to the specific disciplinary aspect the paper aimed to take.

With this directive, I reached out to the prospective author, Brenna, volunteering my assistance. In response, she requested a meeting. Before the meeting, I read her pre-submission draft, a three-page document, two of which constituted the bibliography. I wrote eight comments on the draft, some of which were about unclear expressions or citation errors, and others which commented on the relevance of sources in the bibliography. Most importantly, her write-up was not quite focused on her studied population and the disciplinary lens she was adopting. In my meeting, I emphasized this feedback, and we negotiated a deadline for her to submit the manuscript to the journal.

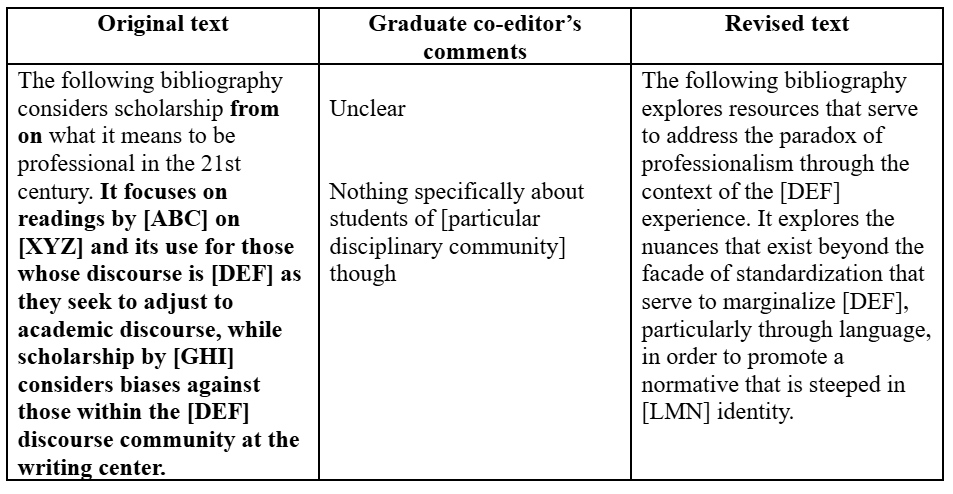

When Brenna returned her manuscript a month after this meeting, it had been significantly changed. It was now a nine-page document with a new title that focused on the discipline and a new section identifying recommendations for the field broadly. In the bibliography section, Brenna had replaced 16 of her references with 19 sources that were more recent and relevant to the topic. Table 1 demonstrates one example of how a graduate co-editor’s feedback was incorporated in Brenna’s write-up by situating the argument in the discipline.

Table 1

Example of Graduate Co-Editor’s Mediation

The extensive changes Brenna made depict the extent of her effort. It is useful to document such efforts as novice scholars do not always have a frame of reference for the time and effort involved in revising manuscripts. Ben, an Anglophone doctoral student in language education, articulates this lack of knowledge as follows:

I don’t know how much work other people do on their article. The only things I only ever see are papers after they’ve been published, so they are in their final form. They are polished. They’re beautiful…[but] papers don’t start out perfect. Studies don’t start out perfect. (Fazel, 2019, p. 86)

Once we received Brenna’s revised manuscript, it was shared with me to confirm if it was ready to be moved to the next stage. In my email response, I wrote:

[Brenna’s] paper seems better aligned now in terms of title and content; however, the references are still not accurately cited in APA format. I guess they can be fixed at a later stage. In terms of fulfilling the requirements of the [particular] genre, it looks ready to be sent out to the reviewers.

These comments suggest that manuscripts can move on to the subsequent stage if major concerns are taken care of and minor corrections can be handled later. Upon receiving this confirmation, the professional editor sent out Brenna’s manuscript to one reviewer because I had worked with Brenna. This practice is in line with the following guideline laid out in Anti-Racist Scholarly Reviewing Practices document: “Editors consider whether full review by two external scholars is truly needed for revised manuscripts” (Cagle et al., 2021). In Brenna’s case it was deemed not necessary.

The reviewer returned feedback in just over seven weeks in the form of both in-line comments and a 636-word long commentary through our submission management portal. To provide perspective on how the reviewer’s feedback aligned with the mentoring mission of the journal, I analyzed the content of the in-line feedback. The analysis revealed that it was quite supportive. Out of a total of 15 comments, two were clarification questions, six were suggestions with an explanation of how incorporating those suggestions would improve the manuscript (including one suggestion for word choice), and three were critical comments that were prefaced by “This is really interesting, but…”. The remaining four comments were compliments (“Good point here!”). The lengthy overall commentary, in itself an indication that the reviewer was invested in helping the author improve the manuscript, was quite supportive and the reviewer had even shared the reference of three readings to help Brenna. To sum up, the reviewer, in accordance with the TPR’s reviewer guidelines (The Peer Review, 2024), acted like a writing consultant.

In response, Brenna submitted a revised draft along with a feedback incorporation grid. In the grid, Brenna addressed the reviewer’s commentary and in-line feedback point-by-point. I was again asked to look through these two documents to ascertain if the manuscript was ready for the copy-editing stage. I reviewed them and said they were. The manuscript was then accepted for publication.

My Analysis of Brenna’s Case

Roen et al. (1995) point out, “Success often does much to build a scholar’s confidence” (p. 241). Wells and Söderlund (2018) explain the outcome of this success: “When [novice scholars] had an article published in graduate school or just after, especially if that article was accepted fairly quickly after its submission, their confidence clearly made writing for publication afterward easier” (p. 141). Brenna’s example illustrates what support for first-time authors can look like: she received consistent mentoring to ensure transparency throughout the review process, and learned how to present her work for external review and how to revise and respond to reviewers accordingly.

Brenna’s example showcases how graduate co-editors can act as critical readers to test a piece before it goes out for external review. Their feedback can ease the sometimes painful review and revision process. In terms of literacy brokering, Brenna’s example has features in common with Lillis and Curry’s (2006) second example, where the brokering resulted in a major shift in content. In Brenna’s case, it is evident that graduate co-editor’s feedback also resulted in a major shift in content. At the first stage, the piece was given credence by the editor by deeming it worthy to be worked upon, and then the comments pinpointed the exact changes that should be made. All this resulted in significant overhauling of the content.

The Case of Failed Mediation: Erin’s Example

Our professional editor put me in touch with the author, Erin, and I reached out to her suggesting my willingness for a meeting. By this point, Erin had already received her first round of reviewer feedback and she had requested mentoring assistance on her post-reviewer feedback draft. Interestingly, it was the professional editor who reminded Erin of this option when feedback was returned to her, perhaps sensing that it was needed. When Erin responded to my email to connect she noted, “I’m not too anxious about the revisions that are needed—more so interested in making sure I provide enough understanding for the intention/direction of the piece, as I feel that was slightly questioned by one Reviewer.”

To prepare myself for the meeting, I went over the reviewers’ feedback and Erin’s manuscript. Erin’s paper was a 20-page opinion-based article in which she had used vignettes from scenarios that tutors frequently encounter (e.g., unclear assignment prompts, students writing for course instructors rather than their intended audience, students’ fear of using their own voice). Reviewer 1 had provided their commentary via a 762-word MS Word document, and Reviewer 2 had sent a 218-word paragraph via email. Both reviewers separately provided in-line comments on the manuscript.

My analysis of Reviewer 1’s commentary indicated that it was predominately evaluative and lacking in writing advice. On the first page, Reviewer 1 had summarized the gist of Erin’s manuscript followed by numbered comments. After copying relevant sentences from Erin’s text, Reviewer 1 had written 10 total single sentence comments as questions (“Don’t they already?”) or critique (“This model does not appear to be new”). Four of the comments began with the word “again,” indicating that there was a persistent problem. I could not categorize any of the comments as actionable suggestions that would aid in revising the concerns Reviewer 1 identified. In terms of praise, there was none. Altogether, this feedback was not supportive and did not fulfill the mentoring mandate of the journal.

On the other hand, Reviewer 2 praised the manuscript as “a really good piece” and offered four suggestions for developing the content. For example, “Consider clumping scenarios into sections (theme based?) with a header and adding additional reflection about voice.” I would characterize this feedback as helpful but brief.

Additionally, before our meeting, Erin sent me a four-and-a-half-page introduction section that she had been revising. After reviewing all these documents, I stated in my notes:

You need to clarify your context, where you are coming from. Because to a different audience these are established good writing instruction practices. So [reviewers] are like what is the value of this? How you play an intermediary role is important.

In our hour-long meeting, Erin shared how she was moving into a new writing center role after being a graduate student, perhaps hinting at her job demands. We discussed the reviewers’ comments and potential revisions. I also shared my feedback with her in the form of in-line comments. We agreed on a date for Erin to submit her revised manuscript.

After the meeting but before submitting her revised manuscript to the journal, Erin reached out to me to look through her submission, which was now significantly longer (30 pages). To quantify her changes, I analyzed the pre- and post-mentoring drafts using the Compare feature in MS Word. The comparison indicated 611 changes were made to the document. She had also added a word to the title, bringing slightly more clarity to the topic. Notably, the argument remained consistent, though how it was presented and framed had changed. Looking at all these changes, I gave her document a go-ahead to be moved to the next stage.

In their second round of feedback, returned in three weeks, both reviewers determined a major shortcoming in the manuscript’s innovation and originality. Reviewer 1 noted that, “The framing is better in the beginning, but I’m still left with feeling like this piece isn’t doing anything new--or isn’t very clearly articulating how what it’s doing is moving the field forward.” Reviewer 2 voiced similar concern noting that the piece did not break “new ground in the WC field.” It was apparent that the type of revision the reviewers requested would require clarity of thought, fair judgment, and significant time and effort from Erin.

The professional editor shared the full reviews with Erin, along with the following suggestions:

What I notice is that you have a strong personal voice but that tying in audience and purpose of their piece at the start of the piece (perhaps at the end of para. 2) might help with some of the framing. In fact, it is OK to hammer home the exigency of your piece throughout the article: “I am writing this because XYZ personal experience AND scholarly gap,” “this piece will be useful for QRS audiences in ABC ways.”

This practice is pertinent to Cagle et al.’s (2021) Anti-Racist Scholarly Reviewing Practices, which includes the following: “editors frame reviewer comments to support author revisions.” Despite this helpful advice from the professional editor, Erin decided to withdraw her manuscript. Calculating the efforts of revision versus the rewards of re-submission, I believe she felt the investment of time was not worthwhile. Another author, working under institutional obligations to publish, may have made a different calculation. Perhaps this publication was not central to Erin’s career goals at that point, or to the new professional role she was transitioning into. In her email addressed to the editorial team, she explained her decision as follows:

I say this more so with concern of the revision requests promoting a direction that this paper never intended to explore, and I believe with further changes, this piece will lose my original intention with/for it and become something that I don’t align with nor am looking to explore as of now, or at this point in my level of experience.

I do appreciate Erin exercising autonomy as she was not willing to compromise her goals for the paper, lose control over her argument, or repress her personal feelings about the piece. In response to her email, I wrote:

I am sorry that you made this decision, but it is one that I truly respect. I also feel responsible for the way things transpired because I believe it is my responsibility to mediate between the author’s goals for a paper and the reviewers’ expectation. There was a communication breakdown somewhere and I am feeling a sense of personal failure here. For you, I hope this experience will not discourage you from contributing to scholarship in our field.

My words conveyed a sense of emotional support as I wanted to make sure this early experience with publishing did not deter Erin’s confidence. The words also bring into focus how I perceive my role as more of a collaborator, accepting responsibility to the extent of feeling a sense of shame in letting Erin down. All in all, this correspondence illustrates my investment in the mentorship process.

My Analysis of Erin’s Case

The examination of Erin’s episode points to three interrelated factors that, in my analysis, may have led to the eventual outcome of Erin pulling her piece from the review cycle: 1) reviewers’ feedback lacked support and clarity; 2) differences between author and reviewer perspectives; and 3) graduate co-editor missing reading a reviewer’s letter to the editors. I take up each of these points below.

Firstly, my analysis of the content of Reviewer 1’s first round of feedback indicated that it fell short of fulfilling the mentoring mission of the journal. Reviewers must remember that writing reviews for a mentoring-based journal differs from a traditional one. TPR’s guidelines are explicit about the mentorship role of reviewers, and those reviewing need to balance supporting the academic integrity of the paper with encouraging the prospective author, which can be quite challenging. Interestingly, in the course of reviewing this case study to write this paper, I learned that Reviewer 1, in the process of reviewing the article, asked the journal for information about the author, which was not the norm. The professional editor provided Reviewer 1 with information about Erin’s academic level along with the note that Erin provided about her manuscript when she submitted her manuscript to the journal (similar to a cover letter submitted to a journal with the manuscript). This note typically goes directly to the reviewers when manuscripts are assigned to them through TPR’s submission management platform, but due to technical difficulties this information did not automatically reach the reviewers as intended. In any case, the request for this further information indicates that Reviewer 1 strived to do their job diligently. On the flip side, it highlights that Reviewer 1 had concerns about the level and background of the author and wanted to keep this in mind when reviewing. In any case, the feedback provided was given with the knowledge of Erin’s academic background details.

Furthermore, I noticed that an overall commentary was missing in Reviewer 1’s feedback. Reviewer 1 had offered a summary of the article, but omitted their opinion of it; this perspective would have more clearly communicated Reviewer 1’s reservations about Erin’s manuscript. Conversely, Reviewer 2’s overall impression of Erin’s manuscript shifted from “a really good piece” in round 1 of feedback to not breaking “new ground in the WC field” in round 2 of review. This change illuminates how reviewers can start to notice aspects that may go unnoticed in the first round of feedback. The shift in feedback may also be due to the time-consuming nature of the review process: in Erin’s email to us about declining to move forward with the manuscript, she noted that authors tend to complete multiple rounds of revision many months apart, and the reviewer may simply not remember what was communicated earlier about a piece they read a year or more ago.

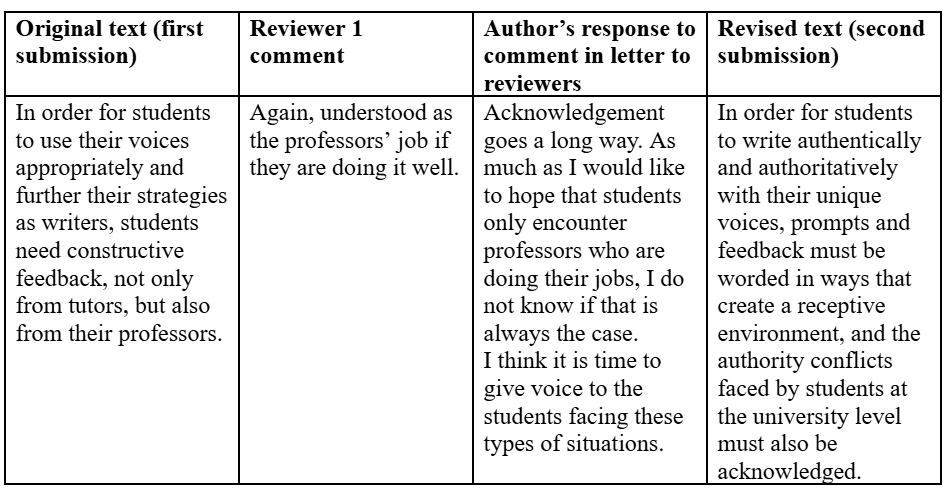

Another cause for the eventual outcome of the manuscript appears to be differing author and reviewer perspectives. It is not that Erin did not revise substantially or did not pay attention to each reviewer comment, as her feedback letter contained specific clarifications and responses to each piece of reviewer feedback. Instead, her point of view differed from the reviewer’s. Table 2 provides a glimpse into how the perspectives differed.

Table 2

Example of Misalignment in Reviewer and Author Perspectives

Table 2 signifies the central issue Reviewer 1 took with Erin’s ideas and how Erin responded and engaged with this feedback. I remembered I had asked Erin in our meeting to add that even if professors do their job right, they might still be unsuccessful; hence, it was important to keep looking for more ways to remedy the situation (see my meeting notes reported in the previous section). Both Reviewer 1’s comment and Erin’s response seem polite in their tone (in my experience there has never been any incivility in such exchanges). Erin’s revised text took out the direct reference to “professors” to accommodate Reviewer 1’s concerns. Erin’s response to Reviewer 1’s comment in her letter is indicative of first-time authors lacking in skills to communicate effectively with reviewers. She rebuts an opinion with another opinion, which was perhaps a less convincing rhetorical move. In an opinion-based manuscript especially, it is essential that the opinion is conveyed effectively. Instead of authorizing her arguments on the basis of her personal professional practice and experience, she could have supported her claims with some references, succinctly connecting her ideas with an ongoing conversation in the writing center field. In her defense, perhaps she misunderstood that this was not an expectation in her piece. She could have also added examples. It is possible that Reviewer 1 was not as concerned with the value of her argument as with the grounding of her argument in personal experience. Considering the second round of feedback, it is clear that Erin did not make a compelling argument and her ideas were not quite agreed with by the reviewers.

Lastly, in reviewing this case study, I discovered that Reviewer 1 had also written a separate letter to the editors, which I had not previously come across. In this two-and-a-half page MS Word document, the reviewer first shared their summary of the manuscript, then their main criticism and questions and their recommendation. Writing a document like that was an unusual practice for TPR’s review procedures. The editorial board did not share this document with Erin for the simple reason that it was meant only for the journal editors. But, it was also not shared with me when I was first connected with Erin. This oversight prevented me from fully realizing the gravity of the issue and understanding the expectations of Reviewer 1 in particular. Had I known the full extent of the reviewer’s concerns, perhaps I would have emphasized this more in my meeting with the author and told her to prioritize this comment in her revision. This is a procedural issue that should be corrected in future.

With regard to Lillis and Curry’s (2006) study, who illuminated literacy brokering “in relation to the experiences of multilingual scholars who live[d] and work[ed] in periphery contexts of the non-Anglophone center” (p. 28), this paper provides further ideas about center-periphery relations in knowledge production. Erin’s refusal to take up reviewers’ feedback may hint at somewhat different power relations for L1 scholars writing for the center. Compared to multilingual writers based in the non-Anglophone periphery, L1 writers may not feel the same power dynamics in an Anglophone center.

Conclusion, Recommendations, and Moving Forward

Using documentary evidence and personal account, this paper demonstrates how explicit remote mentoring provided by graduate co-editors can offer a supportive environment where authors’ skills and confidence in the publication process can be developed. Hence, the paper adds to scholarship on editorship in writing center journals by showing what role graduate student editorial mentoring can play in creating opportunities for emerging scholars in navigating academic publishing after graduate school has ended. It illustrates how graduate co-editors fulfill a journal’s mission of working closely with struggling but promising authors to co-construct their writing and demystify the publication process for them. The paper shows how graduate student editors can be resources writers can rely on to develop texts for publication. It also unveils the labor graduate co-editors dedicate to bringing a publication to the finish line.

In this regard, literacy brokering (Lillis & Curry, 2006) serves as a useful framework to reach some understanding about a graduate co-editor’s involvement in academic publishing by tracing textual mediation. Having access to “medium text history,” which Lillis and Curry (2006) explain as “[t]wo drafts of a text plus more than one piece of related data (e.g., interview discussion, communication or feedback from broker)” (p. 8), I was able to get some insight into this process. While the rest of the textual evidence sources were present in Lillis and Curry (2006), the editorial board’s internal communication was not. By virtue of my unique role, this editorial discourse allowed me to fruitfully use this framework to understand text development.

The description of mentoring stated here indicates that the model of mentoring I implemented is a pedagogical site, similar to tutoring in the writing center. But unlike tutoring, mentoring in the academic publishing space may hold more agency for the editor as extensive mediation in Brenna’s example shows. Furthermore, graduate co-editors do not just help writers improve a specific text; they also have the opportunity to teach authors about the broader expectations implicit in academic publishing, leaving a lasting impact on novice scholars’ professional development.

It is clear from the two cases that student editors mediate text production in a number of ways. Both these successful and unsuccessful examples combined emphasize the need to remain realistic about the impact of graduate co-editor’s brokering. Brenna’s example reflects contributions of graduate co-editors, while Erin’s example unearths the constraints involved. In this way, the paper provides a balanced perspective on mentoring.

Despite being similar in approach, there was one difference between the two cases in mentoring which is worth noting. My mandate in the two cases differed on account of the different stages of the publication cycles the manuscripts were: in Brenna’s case, I worked in a more unfettered manner as I was not yet bound by reviewer feedback and could comment more openly on content development. In Erin’s case, my purpose was more focused on ensuring the reviewers’ feedback was incorporated. The greater flexibility in the first case lends support to the conclusion that mentoring depends on the stage at which it is sought. So, exposure to mentorship at an earlier stage may carry greater benefits than at a later stage. At a later stage, a graduate co-editor’s voice is added to the din, making the first-time author susceptible to being crushed under the avalanche of feedback. Based on the two cases, some practical advice for the main players in the publishing system is offered below:

For Journal Editors

Require reviewers share an overall commentary on the author’s work which communicates a comprehensive opinion about the piece. This benchmarking in review standards is necessary because a high-level, overall commentary can better communicate a reviewer’s impression, which may or may not be clearly captured through localized or scattered comments.

Equip those tasked with mentoring (such as graduate co-editors) with as much information as possible early on so they can make informed choices. Any relevant information or additional communication from reviewers must be shared so they can understand the full picture of the mentorship situation.

Provide graduate editors with resources and training on the publication process as well as mentoring strategies.

Build in graduate mentoring as a typical part of the publishing process and note this explicitly on websites and communications with potential authors.

For Graduate Co-Editors

Seek out information from the author in the first meeting and start the mentoring process as early as possible (for instance, even before the work goes out for review the first time).

Negotiate the evaluative aspect of the work, which is implied when the revised manuscript returns to you to confirm if the work is ready to progress to the next stage. At the moment I am hesitant to exercise authority in approving an author’s work. It is this evaluation aspect which I perhaps did not adequately fulfill as the reviewers disagreed with my assessment. This responsibility requires that editors fully comprehend the author’s skill level, the manuscript, and each piece of reviewer feedback, which takes some skill to develop.

Dealing with the emotional impact of being unable to successfully see a manuscript through is a part of the job. I do not have any pearls of wisdom to offer here, though one needs to dust oneself off and get back up. In my case, not getting Erin’s manuscript further in the process sparked my desire to reflect and write this paper; the call for proposals came when I was dealing with feelings of disappointment from this case.

Rely more on meetings than merely email exchanges to build and sustain relationships. For instance, post-publication, mentees and mentors can have a follow up meeting to know more about mentees’ experiences, what aspects of mentoring they ascertained useful, and how mentoring can be made more effective (e.g., how they feel about mentor’s professional experience and expertise, whether they feel their intervention was dis/empowering, how do they conceptualize successful mentoring, among other questions).

Find out what support for writing or research publication authors have at their institutions to better understand their needs. This suggestion is similar to Inman and Sewell’s (2003) recommendation for electronic mentoring of writing center professionals: “Electronic mentors and mentees should learn about the general institutional and organizational contexts associated with their professional lives, so conversations can focus on the specific needs of each individual in the mentoring relationship, rather than relying on generalities” (p. 188). This information can help the student editors to moderate their level of support because I now believe that mediation cannot be an evenly distributed activity.

For Reviewers

Explicitly draw attention to any major concerns or weaknesses in the first round of review. Any big picture comments should be clearly outlined. Lacking in novelty is a major concern that should have been clearly marked in the initial adjudication of Erin’s manuscript. Later identification of major concerns can contribute to an author’s feelings of frustration, and first-time authors may feel this more acutely.

Writing reviews that fulfill a mentoring mission requires reading authors’ works from a position of support and encouragement. Formal training is required to develop this skill set that requires reviewers to carefully function more as mentors than gate-keepers. Perhaps some reviewers can come forward and run workshops to train writing specialists in the discourses and practices of effective (mentoring-based) peer review.

For Novice Scholars

Seek out mentoring early and often; ask for it if it is not offered right away.

Do not be offended by editors’ feedback; think of it as an opportunity to grow. It takes sustained effort to publish, and two rounds of peer review is not unusual. The exercise eventually benefits the work.

Be open to revision, but realize you still have agency over your text.

To conclude, how graduate co-editors mediate texts as literacy brokers represents only the starting point of mentoring in editorial spaces. Like any other peer mentoring system, this role has enabled me to grow, develop, and learn along with my mentees (the publication process of this article being one obvious benefit). I have deliberately not focused on this reciprocal aspect out of space limitations, though it emerges in this piece where I signal a gaining of a perspective.

As far as the broader discussion of mentoring is concerned, a host of questions remain: What does successful mentoring look like and how to measure it? How mentoring contributes to the professionalization of graduate co-editors? How mentoring would work in case of multiple authorship? How mentoring can help in the empirical research report genre? I hope the writing center community will take up these questions to move the discussion forward. Editorial staff can start off by collectively discussing right at the outset how mentoring should be structured and what it would entail (the do’s and don’ts). Special discussion forums at IWCA conferences can be organized to not only discuss editorial mentoring but also bring student editors together.

References

Arsenault, A. C., Heffernan, A., & Murphy, M. P. A. (2021). What is the role of graduate student journals in the publish-or-perish academy? Three lessons from three editors-in-chief. International Studies, 58(1), 98–115. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020881720981222

Banville, M. (2020). Reflection: Morgan Banville, graduate co-editor. The Peer Review, 4(4). https://thepeerreview-iwca.org/issues/issue-4-0/reflection-morgan-banville-graduate-co-editor/

Cagle, L. E., Eble, M. F., Gonzales, L., Johnson, M. A., Johnson, N. R., Jones, N. N., Lane, L., Mckoy, T., Moore, K. R., Reynoso, R., Rose, E. J., Patterson, G., Sánchez, F., Shivers-McNair, A., Simmons, M., Stone, E. M., Tham, J., Walton, R., & Williams, M. F. (2021). Anti-racist scholarly reviewing practices: A heuristic for editors, reviewers, and authors. https://tinyurl.com/reviewheuristic.

Fazel, I. (2019). Writing for publication as a native speaker: The experiences of two anglophone novice scholars. In P. Habibie & K. Hyland (Eds.), Novice writers and scholarly publication: Authors, mentors, gatekeepers (pp. 79–96). Palgrave Macmillan.

Hashlamon, Y. (2020). Reflection: Yanar Hashlamon, graduate co-editor. The Peer Review, 4(4). https://thepeerreview-iwca.org/issues/issue-4-0/reflection-yanar-hashlamon-graduate-co-editor/

Inman, J. A., & Sewell, D. N. (2003). Mentoring in electronic spaces: Using resources to sustain relationships. In M. A. Pemberton & K. Joyce (Eds.), The center will hold: Critical perspectives on writing center scholarship (pp. 177–189). Utah State University Press. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/usupress_pubs/144

Ives, L., & Spitzer, L. (2023). Student to scholar: Mentorship, recontextualization, and the threshold of scholarly publication in rhetoric and composition. Composition Forum 51, https://compositionforum.com/issue/51/mentorship.php

Lillis, T., & Curry, M. J. (2006). Professional academic writing by multilingual scholars: Interactions with literacy brokers in the production of English-medium texts. Written Communication, 23(1), 3–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741088305283754

Roen, D. H., Villanueva, V., Brown, S., Kirsch, G., Adams, J., Wyche-Smith, S., & Helsley, S. (1995). Revising for publication: Advice to graduate students and other junior scholars. Rhetoric Society Quarterly, 25, 237–246.

Sheffield, J. P. (2014). Networking, demystifying, and connecting: How editing affects graduate student professional development. College English, 77(2), 146–152.

Spooner, M., Weisser, C., Schoen, M., & Giberson, G. (2022). Behind the curtain of scholarly publishing: Editors in writing studies. Utah State University Press.

The Peer Review. (2024). Guidelines for reviewers. Retrieved December 28, 2024, from https://thepeerreview-iwca.org/about/guidelines-for-reviewers/

Wells, J. M., & Söderlund, L. (2018). Preparing graduate students for academic publishing: Results from a study of published rhetoric and composition scholars. Pedagogy, 18(1), 131–156. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/683385.