Praxis: A Writing Center Journal • Vol. 23, No. 2 (2026)

Quantity Over Quality? Defining Educator Flexibility Through Tutor Strategy Use and Session Engagement

Genie Nicole Giaimo

Hofstra University

genie.n.giaimo@hofstra.edu

Sam Turner

University of Texas — Austin

turnersam@utexas.edu

Abstract

This article examines how writing educators—specifically, writing tutors—respond to their training in pursuit of developing “flexible” pedagogies. We offer strategies and assessment plans for writing center and writing program administrators to learn more about how their staff uptake training in their pedagogy, paying special attention to the need for inquiry and assessment measures of local context activity-based writing instruction.

Coda

This is the story of the maddening experience of two authors who tried to bring the article below to publication.

This story starts nine years ago (!) when Sam and Genie–that’s us–first began collaborating on what would become an award-winning article on session notes and tutor professionalization. To say we’re far from where we started is an understatement. Since beginning this work, we’ve both made multiple geographical changes as our academic careers have advanced: Genie moved positions from Ohio State University to Middlebury College to Hofstra University; and after obtaining her undergraduate degree, Sam moved from Ohio State to Carnegie Mellon University, and then to the University of Texas at Austin. We both managed personal challenges and successes and even took time off from academia. Throughout it all, the article that follows lingered in review limbo.

The article, “Quantity Over Quality? Defining Educator Flexibility Through Tutor Strategy Use and Session Engagement,” sat for over a year at one flagship journal with completed reviews unshared with us during that time. We re-wrote the piece multiple times based on the editorial feedback we eventually received, but decided to move on to another journal … that told us it was now too lengthy to publish. After that, we submitted it to a journal that was not accepting submissions, then to another journal that had previously published similar research. One reviewer favorably reviewed the article and recommended it for publication with minor revision; another rejected it because they contested the self-reported data we analyzed was invalid, and because they wanted our study to offer an “assessment of the tutoring situation and what strategies would have been appropriate for use in that situation.” This feedback, in particular, hurt because of its finality; you can’t redesign and carry out a study several years later at an institution where you no longer work.

The study and subsequent article was undertaken in response to what we perceived as a gap in our field, hoping to move beyond a “how to” study on one-off training approaches that was in line with Mackiewicz and Thompson’s research. Our study tried to understand what tutors do in their sessions; to evaluate why tutors do what they do is an even more complex and difficult task. While we hoped for the happy accident of our research answering both of these questions, we realized that our study was a starting point and that our findings would be site-specific and require replication elsewhere. Despite one reviewer’s recommendation to “accept with revision,” our article was rejected for a second time.

We then submitted our article to yet another prominent flagship journal. One year later, we received positive reviews; both reviewers accepted our piece, recommending only minor revisions, which the editor asked us to complete as quickly as possible. We thought we had succeeded...

The reviewers wrote:

Reviewer 1: Thank you, authors, for this thoughtful piece on writing center pedagogy and tutor flexibility. At this time, I am recommending this article be accepted for publication on condition that some minor concerns be addressed.

Reviewer 2: I am grateful to the authors for their work, which I enjoyed as a reader and learned from as a writing center administrator. I recommend accepting this work with revisions that reframe the audience for this piece as more broadly in the field of composition. I hope to see this research in [Flagship Journal] in the near future.

The editor wrote:

You will see that they are advising that you revise your manuscript. I find myself in agreement with Reviewer 1. I think this piece is really good, and is clearly aimed at a Writing Center audience. For publication in [Flagship Journal], I’d like to see you also address a broader [Flagship Journal] audience. This shouldn’t take a lot of work but it is important. While I know why scholarship important to Writing Centers is significant to the broader [Flagship Journal] community, not all readers have that flexibility of mind. Making that argument, especially as part of the flexibility you’re arguing for within the Writing Center environment, will make this piece even stronger. I hope to see this piece again, and quickly!

We obliged—and our article sat with reviewers for another year. Despite the first reviewers recommending acceptance of our article with minor revision, our piece passed through half a dozen more reviewers, all of whom had different ideas about how we should revise. We were left disappointed and unsure how to proceed. Had any of these new reviewers read the revision letters and prior drafts we dutifully resubmitted with each new revision?

One balmy spring day, we were informed that our article was being rejected. We were given no rationale, nor any additional feedback. To us, this was not a meaningful rejection but an insult after a long slog through years of revisions. We knew the editorial team was undergoing transition at the time, but it felt like they were simply clearing their desks.

How could the initial reviews, which were favorable and asked for minimal field-foregrounding of writing center work for compositionists, result in several rounds of R&R and then a rejection?

We don’t have the answers.

Past experiences with hyper-revision–a practice in academic writing that demands several extensive revisions to submitted manuscripts–have shown us that if an author can hang on long enough, there will eventually be a sort of war of attrition where the reviewers (and/or editors) run out of revision feedback. From there, the article or chapter is finally published.

Situations like ours are not reflective of the experience most have with peer review. But what we outline here shows how authors often have to navigate convoluted and labyrinthine publication processes for peer-reviewed journals in our field. This model is damaging. It slows down publication even further in a field that already publishes infrequently compared to other disciplines; it stalls career progress for non-tenure track workers and graduate student workers; and it forestalls meaningful, innovative, challenging, and novel scholarship from reaching its audience.

In total, we revised our article more than eleven times for five different journals.

To say we were given the runaround is polite. To say that this protracted process caused deep trauma in us is accurate. Looking back on this experience, we feel like a process that should welcome novel research into the world became an adjudication on our findings and how we visualized them (which seemed to make several of our reviewers uncomfortable, given their feedback). Yet this article was vetted to the nines; we consulted data scientists and writing studies scholars on our study design, methods, and findings. It was still rejected.

When all this began, Genie was a staff member at Ohio State who wanted to publish in prominent journals and contribute to our field novel findings, research methods, and data visualizations. Sam, who went from undergraduate to doctoral candidate over the course of this process, was excited to grow as a researcher, explore academic publishing, and better understand how the writing center could be a home for her academic and professional goals. “Quantity Over Quality?” was one of our many collaborations; we still collaborate. Yet the frustrating, humiliating, and disorganized path to seeing this paper in print made us question whether we wanted to publish in this field at all, and even whether this field is “for us.”

Nine years later, Genie has published four books (with more on the way) and is the outgoing professional editor of TPR: The Peer Review, a journal that nurtures under-represented voices in writing center scholarship and publishes risky and innovative work (Hallman Martini, 2020). Sam is nearing the end of her PhD program, during which she has held numerous research positions, developed and taught composition courses for undergraduate students and incarcerated adults, and served as a managing editor for Praxis. We’ve both been profoundly shaped by this years’ long publication experience. We’re happy to see this article out in the world, but we are tired. There are other authors in this issue who share similar experiences and who have been brave enough to write about them. Given the number of “hyper-revision” stories we’ve heard from others, there are likely hundreds, perhaps thousands, of cases like ours. Yet we are the lucky ones who ultimately found a venue for publication and our careers were not derailed by this experience.

Guidance for Better and More Ethical Publication Practices

As authors and editors of peer-reviewed journals, we offer guidance for publication practices.

Editors, trust your readers to find out more information if they need it, to figure out research methods and data visualization, and to make connections across sub-areas, including writing center studies. Reviewers, if you do not understand empirical research–as one early reviewer noted in their feedback to us–then recuse yourself from reviewing the article. Scholars, do more primary research across sub-disciplines. Wellness research, for example, is widely published in writing center studies, yet only one article in a special issue of Composition Studies cited writing center research (Miller-Cochran & Cochran, 2022); we need more citational cross-talk across sub-disciplines of writing and rhetoric studies. We ask editors to bring authors to publication, reigning in preference-based feedback that slows down the process for little scholarly gain.

Scholarship in our field should have a space for failure, for preliminary findings, for novel and creative ideas that kick off sub-disciplines. As editors and reviewers, we should approach scholarship with generosity and grace. There will always be opportunity for rebuttal. Scholars can use publication platforms to challenge previously published findings, which is common in other disciplines and leads to more public and generative intellectual debates. Less gatekeeping will help our field produce more vibrant scholarship. Finally, we also need more replicability in our field and deeper citation of the work that has come before.

How many voices have we lost to disorganized and even hostile review processes over the years? We can do better.

Introduction

With all the movement and change that occurs in the administration and staffing at many writing centers, the behaviors and practices that occur in a center during its transitional moments are ripe for exploration. At the same time, these transitions, including the general transience of tutors, make studying behavior and practice in this research site more complicated. Because of these factors, we designed a natural experiment that assessed writing center tutors’ pedagogical development over time. Given that writing centers and writing programs often have similar challenges—employee turnover, varying levels of worker expertise, and a focus on instructional development—our empirical study can be generalizable to scholars interested in assessing writing pedagogy beyond writing centers. More importantly, however, we hope this study will inspire others to explore the concept of flexibility and what we can do, through training and support, to prepare our writing tutors and teachers for the work that they do. Our findings can inform how we train and assess writing instructors in formal (credit-bearing courses) and informal (e.g., writing centers, fellows programs, writing groups) educational settings, as well as how writing program administrators (WPAs) conceive of approaches to training and pedagogical development. To that end, in the conclusion, we offer a set of ways to bring such a study—and its findings—into a training program, although the institutional context for the assessment, as well as its structure, will also need to be considered.

The current study began with an inquiry into how post-session reflective notes in writing centers can help us better understand how tutors professionally develop over time. The authors of this paper (then a new undergraduate tutor and writing center director) initially gave little thought to the common practice of filling out session notes. Unsure of what these forms were supposed to do rhetorically or pedagogically, we developed a longitudinal assessment that applied discourse analysis to session notes to trace how different cohorts of tutors reported engagement with their professionalization. From our analysis, we found that after a couple of semesters (and with intensive training), most tutors—undergraduate and graduate, alike—converged on similar behaviors in-session as well as similar note taking practices (Giaimo and Turner, 2019).

These findings were heartening as they seemed to indicate that our training—and the reflective opportunities that post-session notes provide—was working insofar as it brought some consistency to tutoring practice across a mixed cohort of tutors who had widely different teaching and tutoring experiences. At the same time, however, our tutors were requesting more training and more strategies to teach their writers. These requests were often specific (i.e., “more training on sentence diagramming”) and occasionally emotionally laden (i.e., “more training on how to address student wellness in the writing center” or “more training on how to work through difficult feedback with a writer”), reflecting a common anxiety among new and even experienced tutors that they did not have enough tools to respond to the variety of writers and needs they were encountering. So, we expanded our training modules and doubled down on our activity-based approach to tutor training, which, at the time, seemed to be working well from past assessment. We trained tutors to identify a writer’s needs and strategically apply specific activities, such as concept mapping (Al-Shaer), goal setting (Silvia), scaffolding (Thompson), and point predict (Block), among many others. These advanced training offerings were separate from the “nuts and bolts” of tutor training (i.e., agenda setting, university policies, institutional resources, logistics of day-to-day center functioning) offered at the beginning of each semester and throughout a semester-long undergraduate course. As our training plans grew to some 50 activities that we rotated through annually, we wondered if and how tutors were using these activities in their tutoring work and if the request for specialized training and variety was being met through this model.

Across writing programs, it is difficult to measure how educators take up their professional development. Lillge notes that “not enough is known about whether and how English teachers learn from and apply their professional development” (340), while Zuidema and Fredricksen note that few studies exist on what and how writing teachers “get taught” (13). In writing centers, a tutoring session can be a black box; a tutor goes into it and does something, but what they do is hard to measure unless the sessions are recorded or observed. Even then, there are limitations to how many tutorials a research team can assess—particularly at a center that conducts over 10,000 tutorials annually. Couple this with common challenges in writing programs of all kinds (e.g., worker turnover, crisis response work, last-minute budget and other report requests, etc.) and measuring training uptake and impact becomes even more complicated but necessary work.

Unlike writing teachers—who likely work with the same students, teach a bounded set of texts through planned lessons, and assess assignments according to a shared syllabus—writing tutors (and their administrators) face unique on-the-job variability. At our center, we employed both emerging and advanced tutors from undergraduate students taking on their first tutoring roles to graduate students with years of professional teaching and tutoring experience. These tutors were trained to work with anyone who had a writing need across the university community; in a single shift, a tutor may have seen a multilingual first-year composition student, a staff member working on an article for publication, or a graduate engineering student writing an NSF grant proposal. Basic center-wide training—at our WC and others—then feel like opportunities to get our staff “caught up” to a shared standard of tutoring writing and administrative tasks attendant to writing center work (i.e., filling out session notes, entering timesheets, managing open hours, the “genre” of a tutoring session, etc.) rather than drilling into more specified and complex tutoring methods and approaches. Like WPAs, however, we shared the challenge of working with a large staff with regular turnover which made it seem like were treading the same paths over and over, yet we knew little about how our staff enacted the training we offered.

So, as we built our assessment of training uptake, we conducted a kind of institutional ethnography on our center (Miley). In weekly mentorship groups, we heard our tutors mostly sharing the “same old same old” in terms of how they responded to different writers’ needs and projects. In informal conversations around the center, tutors discussed going back to similar “wells” of tutoring strategies or activities across genres and assignments. In our professional observations of tutors, we noticed a consistent trend of tutors reading papers aloud—despite this being a discouraged practice in our center because of accessibility issues with this method, among other reasons. And, in corpus analysis of tutor session notes (Giaimo et al.), we found that tutors relied heavily upon reading and talk-based strategies in their tutoring work, despite our attempts to broaden tutoring practice to include several other competencies (such as writing, meta-cognitive, and kinesthetic strategies).

At the same time, we regularly fielded requests from our tutors for more and novel training in response to feelings of unpreparedness. This kind of anxiety is present across educational contexts, and our tutors consistently reasoned they needed more training so they could be more “flexible” in their sessions (language they often called upon to describe their need). We were not, however, only responding to our tutors’ requests or affective states; we were also responding to our field’s argument that administrators should prepare tutors to be flexible in their work. As we discuss in the literature review, flexibility is frequently alluded to but infrequently defined in our field’s scholarship. As we thought through our training plans and assessment needs, we realized we were taking for granted a shared definition of flexibility, with impacts across all levels of center functioning, from high-level training to on-the-ground tutorial work.

We wanted to get closer to understanding what “flexibility” meant in the Ohio State University (OSU) Writing Center, specifically, which included examining how tutors were using the training we developed in response to their calls for 1. increased training, and 2. access to strategies they reasoned would result in “flexible” tutoring practices. We assessed training uptake by conducting discourse analysis and frequency analysis on session notes, a form of passively collected data in many writing centers. Our study asked the following questions:

How many and what kinds of strategies do tutors report using?

Does strategy-use change over the course of a tutor's career?

What can analysis of strategy use and training uptake tell us about flexibility?

Measuring perceived flexibility in informal writing education settings can give us deep insight into applications for teachers and administrators of formal writing education settings. It can also clear up the anxiety that educators might feel to include more and varied pedagogical approaches that may not suit them individually and/or the learning situation. Yet, flexibility is a common shorthand in many pedagogical spaces, though it can be murky in its enactment. The Council of Writing Program Administrators (CWPA) identifies flexibility—“the ability to adapt to situations, expectations, or demands”—as one of the habits of mind necessary for student success in postsecondary writing (1). This framework encourages writing teachers to foster flexibility by practicing different writing tasks and doing reflective work with students (8). Unsurprisingly, CWPA’s guidelines closely align with best practices in writing center tutorials mapped out in guides like the Longman Guide to Peer Tutoring. Teacher training in this instance looks a lot like tutor training and praxis, though both can be difficult to measure.

Little is known about how writing tutors apply flexibility to their tutoring pedagogy. To understand tutors’ behavior, we turn to Boquet who describes tutoring work as “…improvisation [that] is largely about repetition, repetition, repetition. It is also a consequence of expertise, of mastery, and of risk” (76). Like Boquet, we found that tutors developed expertise and mastery of particular strategies; however, they did not take risks (the last of Boquet’s improvisation trifecta) as we had hoped they would through implementing novel tutoring strategies. Instead, they repeated a bounded set of tutoring practices, hitting the same few notes repeatedly (76). Our hypothesis—built from our tutors’ attitudes towards training and reading in our field’s scholarship—that a “more is better” approach to tutor training was complicated by our findings that across the whole of tutors’ careers, they use a small number of similar strategies (4–7, on average) and roughly two and a half strategies per 45-minute session. Furthermore, tutors had bounded tutoring repertoires which we coded into four different groups—the readers, talkers, grammarians, and wild cards. Flexibility, then, might be found in group-level rather than individual level praxis.

This study is an exploratory foray into examining tutor pedagogical practice around adoption and application of learning strategies that foster writing development. We hope scholars at other institutions replicate our study—even its most basic elements, such as asking workers to report on the number and types of strategies/activities they use in their writing pedagogy—and think with us about how flexibility is enacted in different writing education spaces, especially considering how ubiquitous flexibility is in how educators (emerging and experienced) talk about their work. Our assessment model can also be adapted for writing programs, which share many similarities with writing centers in terms of learning goals, hiring practices, pedagogical approaches, and training programs.

Literature Review

Questions around flexible pedagogies and classroom practices are especially visible in an educational landscape shaped by a global pandemic (Johnson-Eilola), as shifting learning environments mean “flexibility” has been taken up by educators and support staff across disciplines in response to digital and distance learning (Campbell-Gibson, et al.; Johnson-Eilola and Selber; Kirkpatrick). However, education researchers have been seeking definitions and applications of teacher flexibility since before the new millennium, often in response to the development of digital spaces and pedagogical implications of the internet (Kirkpatrick; Dennis). In writing classrooms, even pre-pandemic, composition scholars have been preoccupied with thinking about flexibility in relationship to how students use technology and tools in the writing classroom to facilitate their learning (Gierdowski). Writing centers, too, have talked about digital pedagogy for decades (Closser; Hobson) and frequently provide online writing support alongside in-person tutorials.

However, in writing center studies, research around flexibility has been seemingly lacking, despite being studied broadly across disciplines (including music and arts, business, social sciences, and education). One educational studies scholar, Burge calls to interrogate the intent and practical application of the term “flexible” within educational spaces: “The word flexibility and its adjective root, flexible, have gained such popularity in higher-education discourse and marketing strategies over the past few decades that it is time to dig into these words anew, with reflective and critical intent” (1). Likewise, Kirkpatrick asks “How can we provide flexibility without complexity and create minimal confusion for our students and staff? How much choice is too much?” (Kirkpatrick 20; emphasis added). Much like we do in our work, these scholars recognize that flexibility is more than just digital learning pedagogy or multimodality, yet they too struggle to come up with assessable approaches to identifying and defining this term as it relates to teacher development.

For our study, we did a keyword analysis on the term “flexibility” (and derivatives of it, like a broadly defined “flexible” approach to tutoring) in writing center and writing classroom scholarship. From this, we found that “flexibility” encompasses far too many attitudes, practices, and standards to be easily enacted by teaching and support staff. And, sometimes, when it is enacted, it might not necessarily be productive (think here about new tutors doing things to see what “sticks to the wall”). Furthermore, concepts of flexibility as expansive and wide-ranging contradict research on teacher development, which often points towards specialization—rather than broadening—of one’s pedagogical skillset as a sign of expertise (Sun et al.; Li).

Training manuals, such as The Longman Guide to Peer Tutoring (Gillespie and Lerner), identify tutor flexibility as a primary development goal: “Our goal...is for you to develop...flexibility” (48). To manage educational outcomes and content of a tutorial, the guide advises “flexibility and control” (Gillespie and Lerner 55). They write, “The important thing is to approach a session with a curious and open mind, and to develop...the flexibility to know what's working in a session and what adjustments you need to make” (59). While training materials often extol flexibility, tutors—at least in our writing center—reported struggling with being flexible but also deliberate in their sessions. So, we responded to tutors’ requests for support and training focused on flexibility but then we also conducted assessment to see what might be going on in-session with how tutors approach their work.

In the field, flexibility is described as “the hallmark of good teaching and tutoring” (Blau et al. 38) and is held in contrast to writing center “orthodoxy” as a best practice (Gill 172). Irene Clark argues “for the necessity of developing a flexible approach to the issue of tutor directiveness and… differences in students’ learning styles” (46). Malcolm Hayward understands flexibility as a tutoring strategy in and of itself that is primarily enacted to support writers and faculty (8). Ashton-Jones echoes Hayward, and advises “tutors to remain flexible and responsive to tutees’ needs, however and whenever they are presented” (33; emphasis added). Still others (Blau et al.; Hitt) declare writing centers to be spaces with “flexible pedagogies” (Hitt 3). Especially in earlier writing center scholarship, tutor flexibility seems aspirational rather than fully enacted, which might speak to the challenges that North describes in his set of seminal pieces on writing centers (North, “The Idea of a Writing Center”; North, “Revisiting ‘The Idea of a Writing Center’”). Because of their service role in the institution and frequent connection to writing curriculum, writing centers are frequently placed in the impossible position of being everything to everyone. In this kind of service model, it is no wonder that flexibility becomes a stand-in for what might be more appropriately termed responsiveness. In placing the burden of flexibility onto the tutor (and leaving it largely undefined except in relation to the needs of faculty and writers), these pieces do not deeply examine or describe what tutors need to do to become flexible beyond asking them to respond to others’ needs.

There are, however, a couple of studies that explore how flexibility impacts tutor professionalization and pedagogical growth. David Healy argues that writing centers are rushing to catch up with their own growth and development in terms of professionalization; therefore, many of the roles that tutors play are not explicitly articulated or supported in writing center work. Shifting between roles in writing center work can lead to “role conflict” in which a “tutee’s expectations conflict with [the tutor’s] own preferred style or with their assessment of the best role to adopt in a given tutorial session or at a given tutorial moment” (Healy 46). Tutors mitigate role conflict by adopting rigid or flexible tutoring stances. However, these stances are not net positive and net negative roles: “…one might assume that flexible coping strategies are inherently and necessarily superior to rigid ones. But in the tutorial context, rigidity may at times be advantageous” (Healy 47). In attempting to be “all things to all people,” flexible tutors may lack effectiveness, while rigid tutors may have a “keener recognition of institutional reality,” and are therefore better prepared to support writers who are facing performance pressures in their courses (Healy 47). Flexibility, then, is related to the professional context in which tutors labor.

Flexibility is also mentioned frequently in recent scholarship (Henning; Thompson et al.; Silvey; Van Waes et al.; Trosset et al.), though it is often undefined and disconnected from specific tutor pedagogical practice. However, Nancy Grimm, like Healy, centers tutor professional (and personal) identity when discussing flexibility. Grimm notes:

In a writing center that embraces a concept of multiliteracies, effective tutors learn to engage with difference in open-minded, flexible, and non-dogmatic ways. Effective tutors learn to shift perspective, to question their assumptions, to seek alternative viewpoints… to determine where necessary knowledge might be missing, and they develop strategies for supplying that knowledge. (21; emphasis added)

In articulating a vision for how tutors can employ flexible tutoring effectively through the development of responsive pedagogy, Grimm identifies the tutor’s role as an interpreter and communicator. Because tutors encounter heterogeneity in the academic, social, and professional spaces that make up writing centers, flexibility is a process that hinges upon communication strategies, inquisitiveness, awareness of identity roles, and the development and adoption of culturally responsive and anti-racist tutoring strategies. Flexibility, then, is rooted in tutor identity and pedagogical behavior (as well as educational context), not in response to broadly conceived faculty or student need.

Our review of the literature found that flexibility is used as a catch-all term for pedagogical work in and around writing centers. In contrast, our IRB-approved study—inspired by Grimm’s argument that effective tutors develop a multiplicity of tutoring strategies to respond to writers’ needs—examines the rich and varied tutoring strategies that tutors employ to uncover flexible (or otherwise defined) response pedagogies. We conducted a longitudinal study on strategy use among tutors in the OSU Writing Center, and found that tutors—despite echoing the “language of flexibility” so commonly found in our field—utilized far more bounded and patterned sets of strategies than were made available to them. This study, then, begs the question of what a flexible writing tutor-educator looks like and whether we might benefit from understanding writing centers/programs—rather than individuals within them—as flexible. Another possibility is that flexibility need to be more fully interrogated through both localized and field-wide inquiry into its meaning and application by our tutors and administrators alike.

Method

This IRB-approved study was conducted at the writing center of a large, Midwestern, land grant institution, where writing center staff (n = 50) hosted over 10,000 appointments annually. Tutorials were almost evenly split between undergraduate and graduate clientele with faculty, staff, and postdocs comprising ~10% of clientele.

Subject Participants

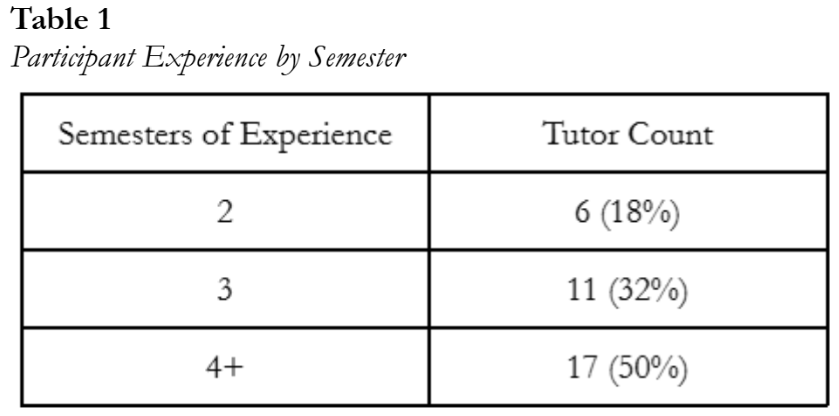

We randomly selected notes from 34 undergraduate and graduate tutors from a larger pool of 78 tutors. Tutors had at least 2 semesters of experience, with a range of 2–6 semesters (Table 1). Semesters of experience were roughly even between undergraduate (~3) and graduate tutors (~3.2).

All tutors attended training weekly, monthly, and semesterly for a total of ~55 hours of training annually. Undergraduate tutors also enrolled in a semester-long full credit tutor training course, while most graduate tutors had prior writing center experience and pedagogical training. The turnover rate at the writing center was roughly 45% each year, meaning approximately 23 tutors graduated or moved on from their tutoring positions. On average, undergraduates were employed by the writing center for 1.7 years (4 terms), while graduate students were employed by the writing center for 2.2 years or 6 terms.

Materials

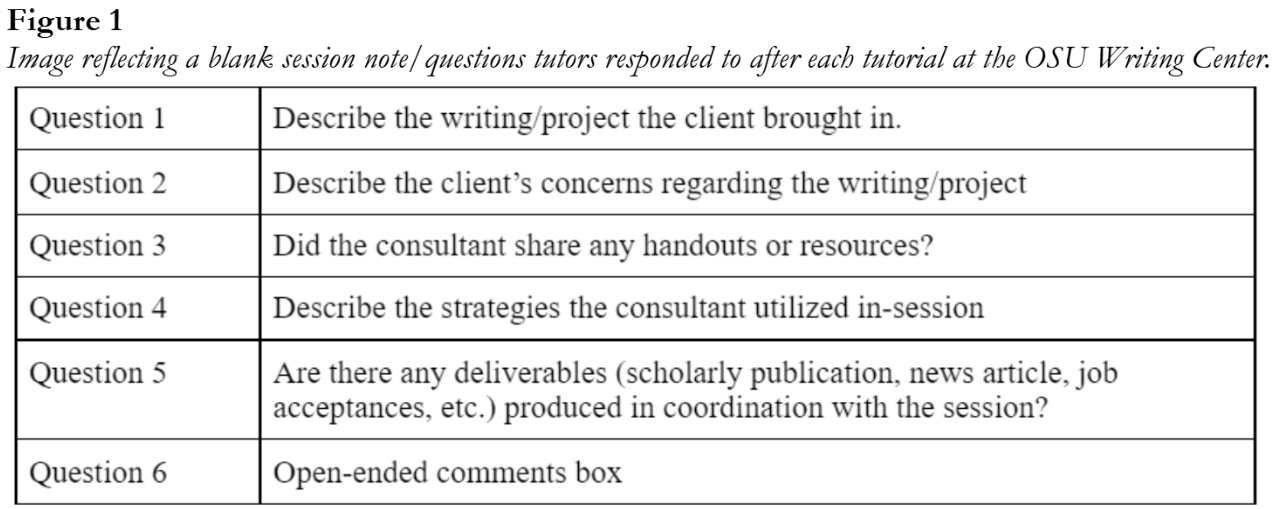

We collected 1,110 session notes from WCOnline. The form (Fig. 1) includes open-ended and checkbox questions. 10 session notes were collected from each tutor for each semester that they worked. Tutor candidates and their notes were identified for coding using a random number generator (Excel).

Data Coding and Rubric Development

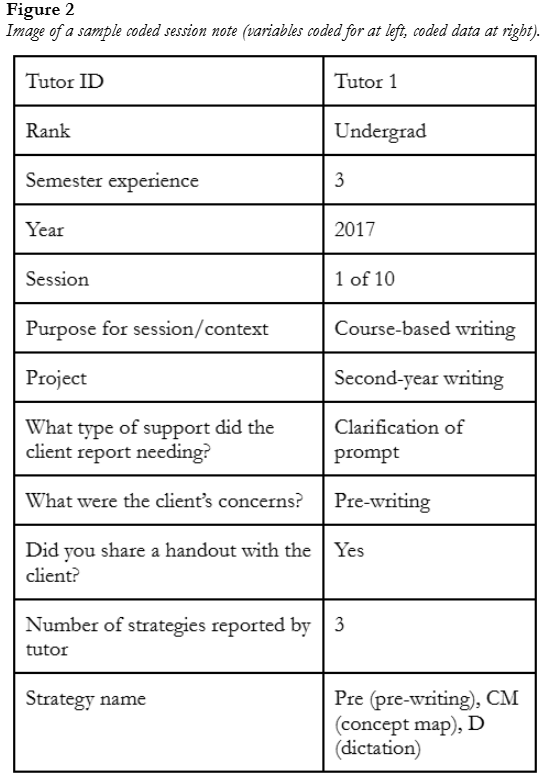

The two researchers engaged in four distinct rounds of note coding, discussion, and rubric development. After determining which questions to analyze (all but number 5), identifying coding categories, and measuring interrater reliability (~95% agreement) on a subset of the dataset (n=150), all notes were fully coded in Excel. We coded each note for 12 variables (Fig. 2), including demographic data (tutor ID, rank, semester, year), session context, and tutor behavior in individual sessions (whether they shared handouts, the number and type of strategies used).

The researchers further coded the 37 most frequently reported strategies that tutors reported utilizing in-session and classified these into groupings (Appendix A). Most of these strategies were derived from the OSU WC training modules (~55 hours annually) (Appendix A). The researchers also coded a few organically developed strategies that tutors reported using, including dictation and direct grammar instruction. Strategies were grouped together based on common, stemmed language. For example, tutors reported “concept mapping,” “concept maps,” and “mind maps,” all of which were grouped together under “concept mapping” or “CM.” After stemming, 37 strategies were identified, including an “Other” category for strategies that the researchers were unable to identify or classify due to lack of a clear description in the tutor’s note. Shorthand codes were assigned to each strategy so that scaffolding was denoted as “Sc,” pre-writing was indicated as “Pre,” brainstorming as “B,” etc. Individual strategies were further coded into functional groups of similar strategies (Appendix A).

Analysis

To measure how different variables affect the number of strategies that tutors used per session, we ran an ANOVA with blocking on the independent variable of strategy number used by a tutor within an individual session in relation to the following predictors: tutor ID (subject participant; block), tutor rank (undergraduate/graduate), semesters of experience (of tutors in the writing center), handout use (whether or not handouts were used by tutors in writing center sessions), and session context (if the client brought in course-based/assigned writing or personal writing). All variables were initially coded in Excel and then selected variables were analyzed in RStudio using nlme package version 3.1-137 (Pinheiro et al.).

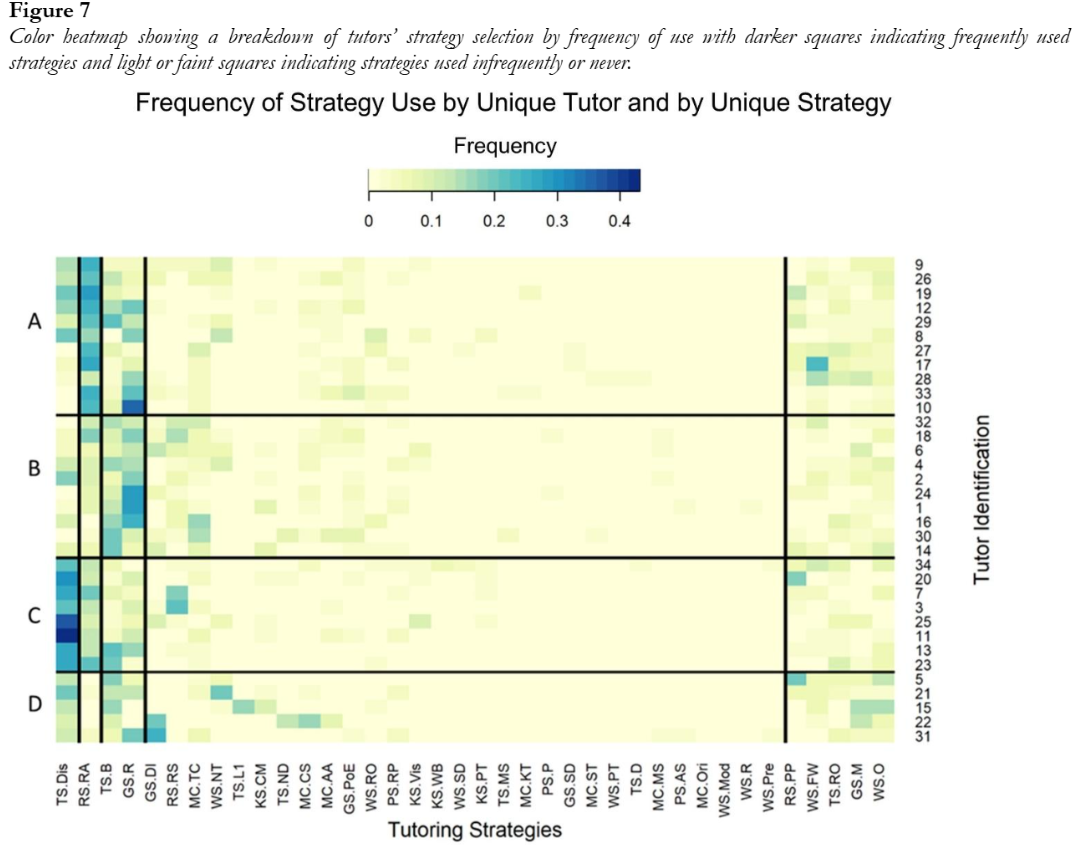

Since not all tutors had the same number of notes or used the same number of strategies, we normalized our data, in Excel, by calculating the frequency with which a tutor used a strategy. We then created a heatmap (Hung et al.) that uses a hierarchical clustering technique to group tutors by most frequently used strategies in R Studio using gplots package version 3.1.0 (Gu et al.).

Results

Overview of Findings

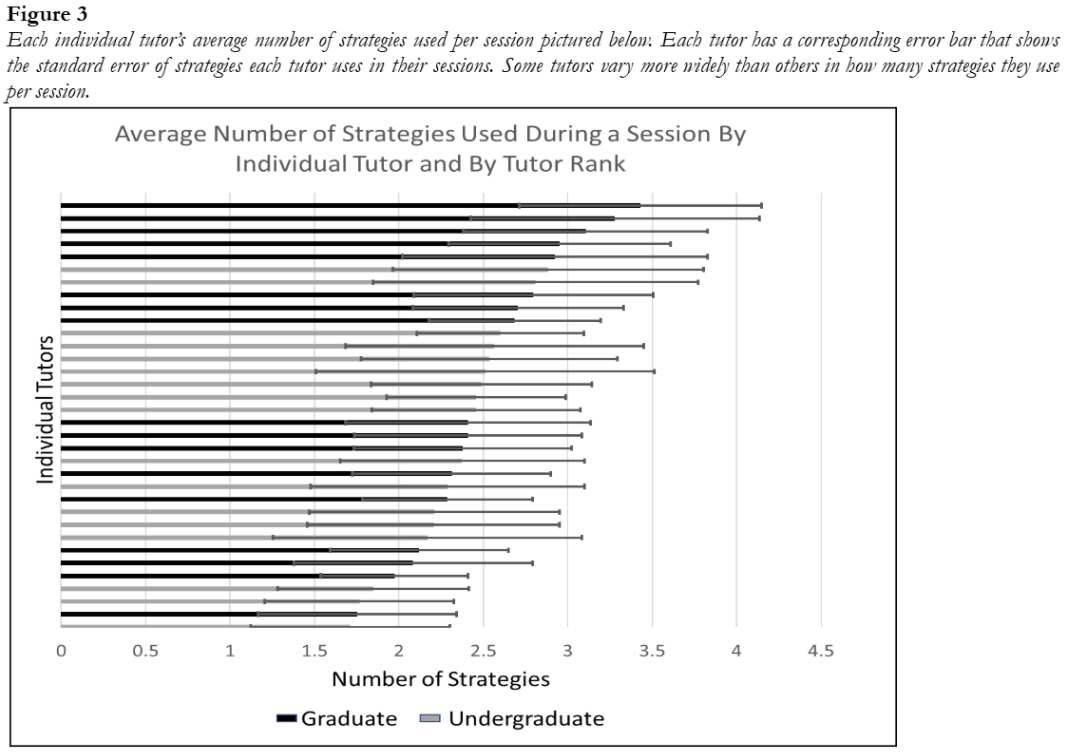

Tutors are a highly individualistic population, though their practices are significantly impacted by their semesters of experience by rank as well as by session context (Table 2) (Figs. 4–6). There is high variation (standard deviation = .83) in the number of overall strategies tutors utilize in-session ranging from 1–5 strategies, with an average of 2.26 strategies per 45-minute session and a lot of individuality in the different strategies that tutors utilize (standard deviation = .44–1 strategy) (Fig. 3). Tutors ranged in their use of single strategies from frequently (~50) to almost never (~1). The heatmap (Fig. 7) shows the frequency with which individual tutors utilized strategies, with some strategies (e.g., read aloud and talking strategies) used often and others (e.g., motivational scaffolding) used infrequently.

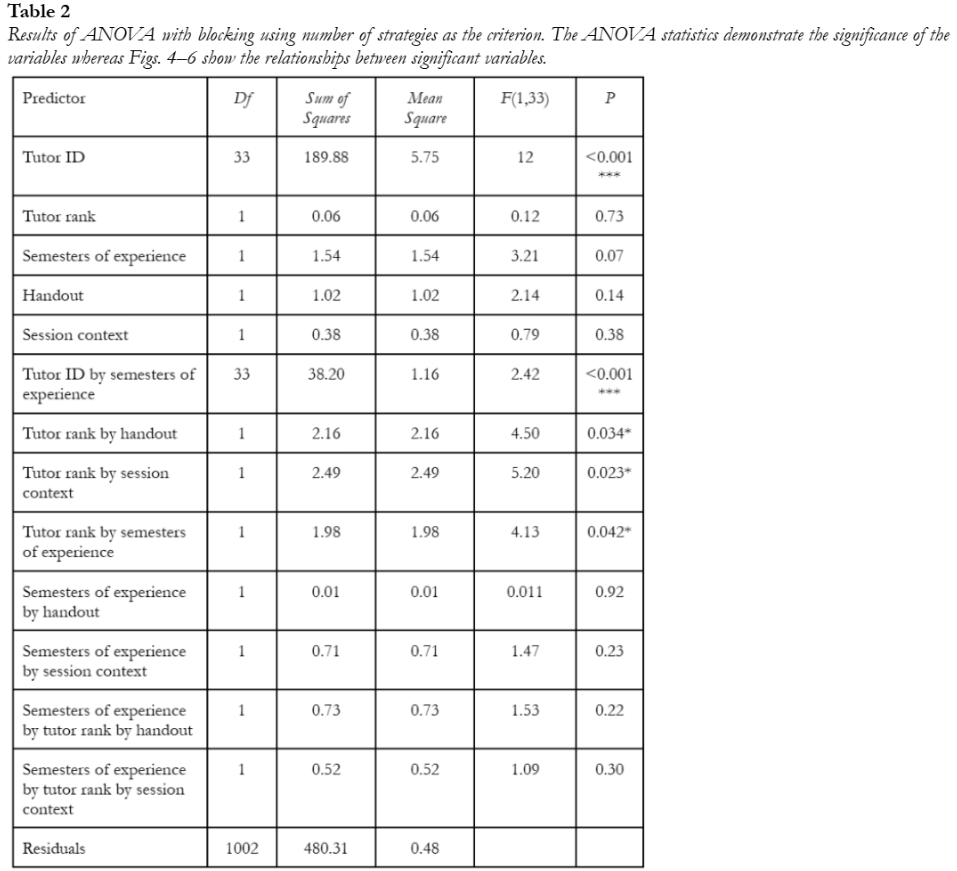

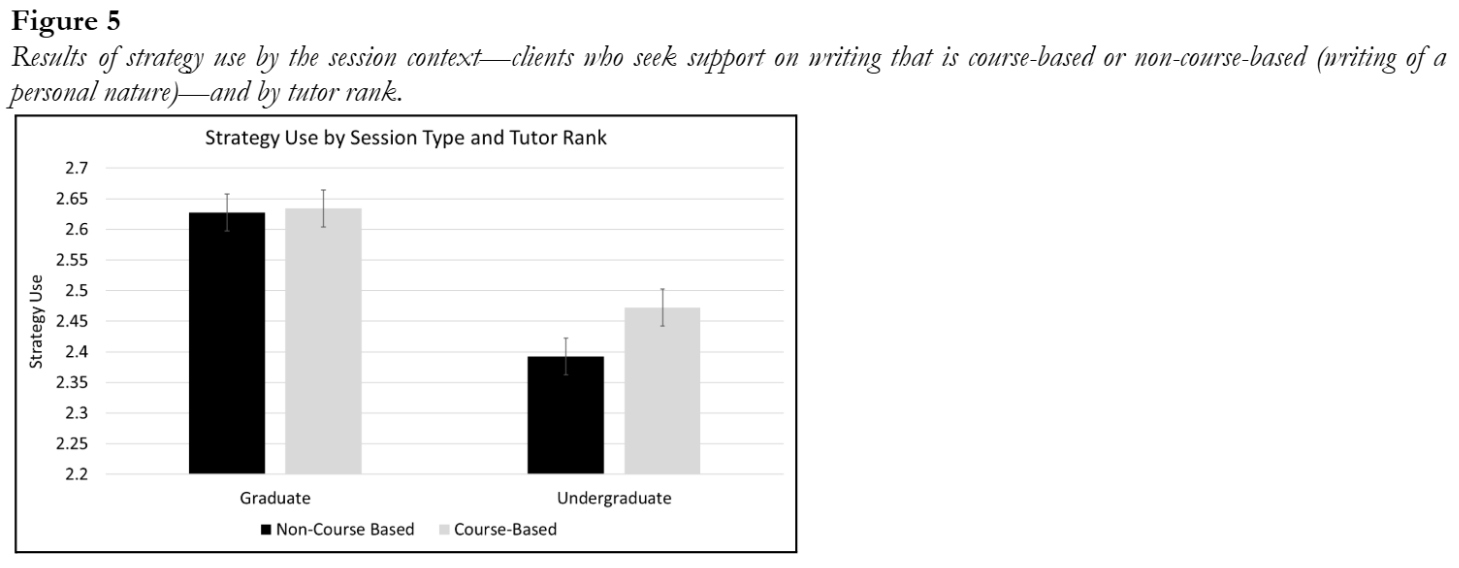

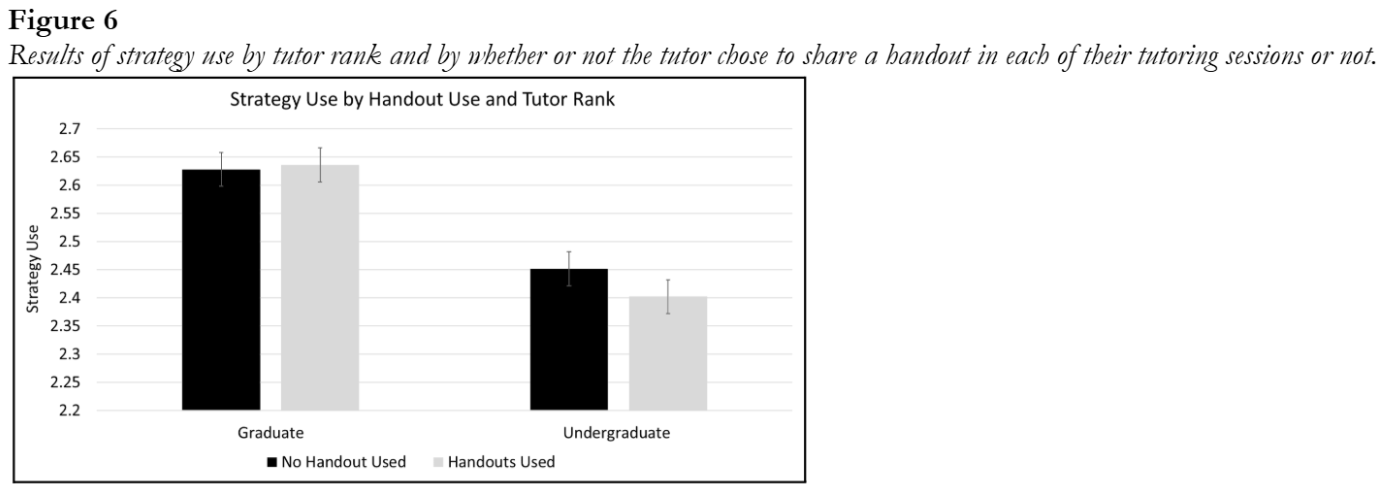

Significance by p value (p<0.05 (*), p<0.01 (**), or p<0.001 (***) and effect size (F statistic) was determined for the results of the ANOVA. Of the predictors, tutor ID (F 1,33 = 12, p<0.001) and tutor ID by semesters of experience (F 1,33 = 2.42, p<0.001) were both highly significant, although there was a low effect size on tutor ID by semesters of experience. Tutor rank by handout use (F 1,33 = 4.50, p < 0.05), tutor rank by session context (F= 5.20, p < 0.05), and tutor rank by semesters of experience (F 1,33 = 4.13, p < 0.05) were all significant with high effect size (Table 2).

Interpreting ANOVA

Analysis of variance (ANOVA), a set of statistical tests that compares group mean differences in an experimental dataset, was used to measure how different variables affect the number of strategies that tutors used per session. In this analysis, several variables were compared and the means that were significantly different (P value and F value) were identified (see Table 2) and interpreted (see Figures 4–6). Review this link for more details about ANOVA (analysis of variance) and F tests.

Findings from ANOVA of Strategy Use by Variable

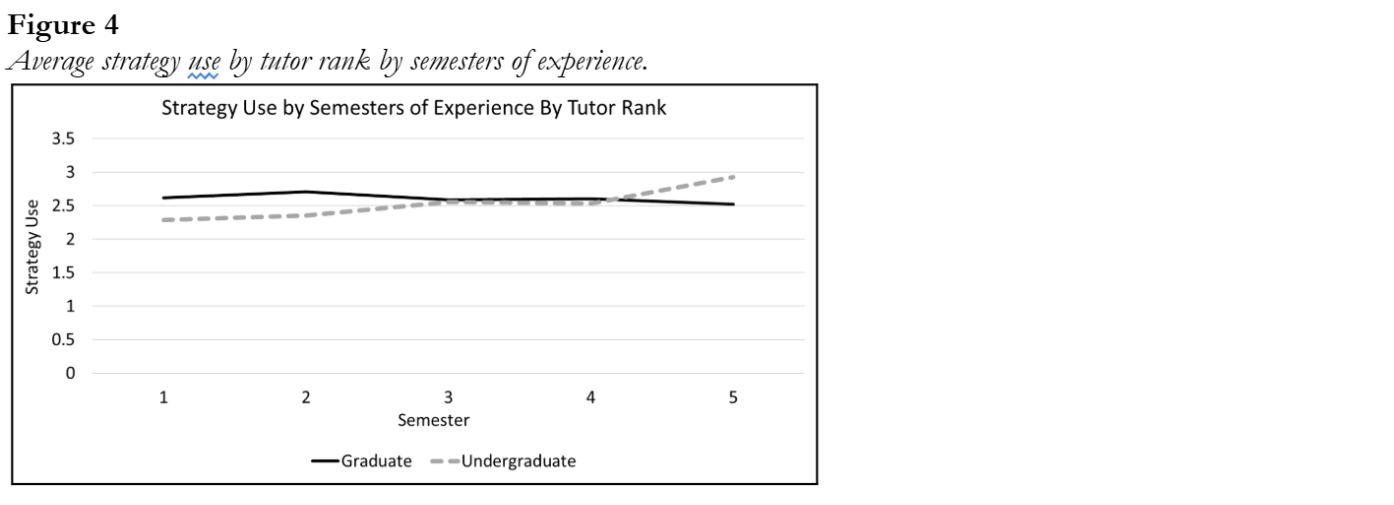

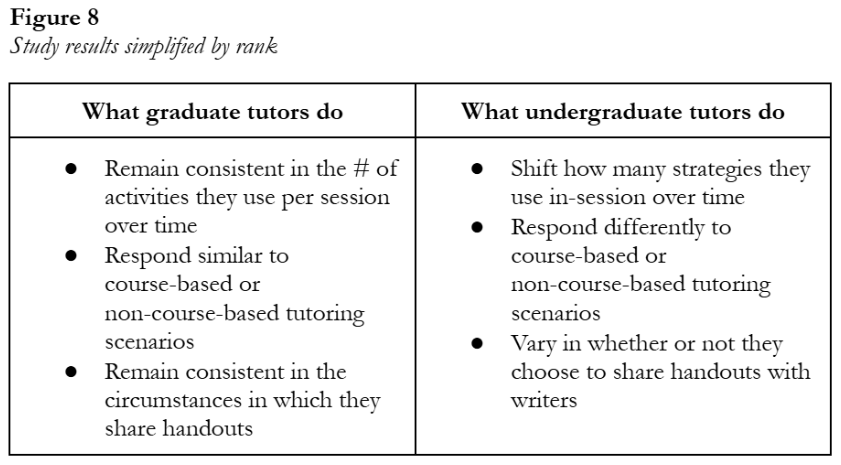

Results suggest that tutors are largely individualistic (F 1,33 = 12, p<0.001) in the number of strategies they utilize per session (Table 2), and that while semesters of experience affect an individual tutor’s use of strategies (F 1,33 = 2.42, p<0.001), the low effect size indicates a lot of variation around that trend with some tutors changing more than others. This indicates the number of strategies tutors use is affected by not only the number of semesters they worked in the writing center but also their individual starting points and movement towards an optimum. Undergraduates increase the number of strategies they use in their sessions as they work more semesters in the writing center, while graduate tutors remain consistent in their strategy use regardless of their semesters of experience working in the writing center (Fig. 4). Tutors’ use of strategies is also affected by their rank in specific contexts related to circumstances surrounding tutoring sessions, such as the kind of writing a client brings to their session, and whether or not handouts are shared, in-session. While rank is not a significant predictor of behavior on its own, it is significant when considering tutors’ semesters of experience (Fig. 4), the number of strategies used in tutoring sessions focused on writing assigned by a course (Fig. 5), as well as sessions in which handouts are shared (Fig. 6), with undergraduates changing their behavior in all of these circumstances.

Heatmap of Tutors by Strategies by Semesters of Experience

A heatmap that shows hierarchical clustering (Fig. 7) was created to track how often tutors engaged in specific tutoring strategies. Darker colors indicate low usage or no usage of specific strategies while brighter colors indicate frequent use of specific strategies.

Interpreting the Heatmap

The key components of the heatmap include the individual squares that comprise the map, as well as the labeling along the bottom edge. The letters along the bottom of the heatmap denote the 37 most frequently used strategies, all of which tutors were trained to use. Starting from the bottom left, we see “TS.Dis,” which was the researchers’ shorthand for “Talking Strategy, Discussion.” In this format, “Talking Strategy” refers to the “family” code—a related group of activities that individual strategies were coded under—while “Discussion” is the individual strategy that tutors reported utilizing. Likewise, the rightmost label, “WS.O,” stands for “Writing Strategy, Outline,” again indicating both the “family” of activities (writing strategies) and the individual strategy (outlining). See Appendix B for the full list of strategy groupings and acronyms.

Heatmap Findings

The heatmap (Fig. 7) displays findings by strategy (columns) but also by individual tutor (rows), listed by random identification numbers along the right edge of the heatmap. To see what strategies a given tutor uses, follow the tutor ID horizontally across the heatmap (for example, we can see that Tutor 10 is one of the only tutors to report very frequently using “GS.R,” the grammar revision strategy). Likewise, if you start at the bottom and follow an individual strategy vertically up to the top of the map, you can see how often a given strategy was used by all tutors. The columns (especially on the left side of the heatmap) show significant variation amongst individual tutors, while the horizontal lines denoting groups A-D highlight tutors’ patterned strategy usage. Because each row of the heatmap represents a different tutor, each square in each column represents a unique strategy used by a unique tutor.

Out of the 37 most common strategies that tutors identified using, and keeping in mind that tutors used, on average, 2.26 activities per session, tutors often reported utilizing between 2–4 common strategies across multiple sessions, though a subset of tutors utilized a more diverse array of strategies. See Appendix B for a full list of strategies, including those most commonly used by tutors in their sessions.

From reviewing the heatmap, four groupings of tutors by strategy use were identified, post-hoc:

Group A (the readers): used writing and reading strategies, such as free writing and read aloud with heaviest focus on the read aloud strategy (RS.RA), which they reported using during about 25%-30% of the sessions they conduct.

Group B (the grammarians): used grammar-focused strategies such as direct instruction and modeling, with heaviest focus on revision (GS.R) and brainstorming (TS.B), which, between both of these strategies, they reported using in about 50% of the sessions they conducted.

Group C (the talkers): used talking strategies such as discussion, read aloud, and brainstorming with heaviest focus on the discussion strategy, which they reported using in about 30% to 40% of the sessions they conducted.

Group D (the wild cards): used a wide range of strategies, including discussion, but also kinesthetic and meta-cognitive approaches, such as concept mapping and threshold concepts that were not commonly utilized by the other tutors. They are highly individualized and experiment across many different strategies though many of them had a go-to set of 4–9 strategies that they used most often in their sessions.

Discussion

The differences in tutoring practices between undergraduate and graduate tutors (Fig. 8) beg the question of whether variation in strategy usage is synonymous with flexibility. Whereas graduate tutors remained largely consistent in this element of their tutoring practice throughout their tenure, undergraduate tutors had significant change in the average number of activities that they utilized; by the third semester of employment, they moved in-line with graduate students’ activity use, and by the fifth semester they used roughly half a strategy more per session than their graduate tutor counterparts (2.9 and 2.5, respectively) (Fig. 4). The initial difference between these two group’s behaviors might be due to the different ways in which they were trained and recruited into the writing center (undergraduates through a course, graduates through a summer workshop). Yet, a previous study found that tutors—irrespective of rank—begin to coalesce in the ways they describe, evaluate, and reflect upon their tutoring sessions, which suggests that time, rather than rank, is an important driver of change (Giaimo and Turner, 2019). Considering our previous findings that undergraduate and graduate tutors utilized similar amounts of strategies after a few semesters of work, we believe that there is a cohort effect that takes place where tutors of different ranks and training backgrounds learned from each other and developed shared practices (irrespective of flexibility). One takeaway for WPAs and WCDs is that there are a lot of potential positive outcomes surrounding pedagogical development that arise from mixed rank tutor-educator training models.

Flexibility, however, cannot be identified through our grouped analysis of undergraduate and graduate tutor practices because it fails to capture how individuals coalesce into different and mixed-rank groups composed of relatively similar numbers of undergraduate and graduate tutors. Therefore, turning to the heatmap (Fig. 7) might help us to further articulate a theory of flexibility for writing center pedagogy that moves beyond understanding group differences as indicators of flexibility.

The heatmap shows four distinct groups of tutors who utilized strategies in ways that are like those in their group. Group A (the “readers”) used a broader range of strategies with frequent use of strategies in reading and writing domains. Group B (the “grammarians”) was similar in scope to group A but used more grammar strategies and fewer writing and reading strategies. Group C (the “talkers”)—a smaller cohort of tutors—relied on talking strategies (discussion in particular) more than any other group and utilized reading strategies similarly to group B. Group D (the “wild cards”) was the smallest cohort of tutors. This group did not rely heavily on any one strategy or type but instead used a wide range of the more popular strategies, including talking, reading, writing. Group D also used otherwise under-utilized strategies that were included in training by tutors’ requests, including kinesthetic and meta-cognitive approaches, such as concept mapping and threshold concepts, more than the other groups. WPAs and WCDs should assess the pedagogical practices of writing tutor-educators for patterns of bounded strategies/practices, especially as they relate to site-specific training models.

While tutors’ use of strategies fell into general categories, there was still variation among individual tutors. Tutors in most groups relied on a specific strategy between 25% and 40% of the time that they tutored, yet they showed individuality in the strategies they utilized the rest of the time in their sessions. These findings suggest that tutor behavior was far more complex than an upward or downward trajectory with regards to strategy use. The implications of this finding for WCDs and WPAs is that tutors rely on bounded yet patterned sets of learning strategies that do not necessarily scale up or change from educational context-to-context. This “less is more” finding suggests that we ought to re-think our professional development training models and goals.

Is Variety the Spice of Life? Tutoring Practice as Individualistic and Bounded

Our hypothesis about flexibility—that tutors who are trained to use more and different types of strategies will do so—does not pan out. While groups A–D are composed of tutors that behaved similarly to those in their groups, there was still a lot of variation at the individual level. Additionally, some groups (A and C) relied on a more bounded and commonly shared set of strategies, whereas others (B and D) utilized a wider range of strategies. In different groups, tutors ranged from utilizing one type of strategy in 25% of their sessions (Group D), to 35% (Group A), to 40% (Group C). This suggests that tutors had varying levels of comfort or interest in deploying different strategies; however, we are hesitant to label one group of tutors more flexible than another given the wide range of variation at the individual tutor level, as well as the clear reliance on single strategies among most tutors in most groups.

Additionally, the range (1–5) of strategies that tutors used per session suggests that there might be upper and lower limits on the number of activities a tutor felt comfortable utilizing in a 45-minute tutoring session. Therefore, any assumptions about a “more is better” approach—a sentiment tutors echoed in their requests for more and varied training—to tutoring being synonymous with flexibility needs to be interrogated given the inherent time constraints on most tutoring sessions. A final takeaway, then, is that we ought to interrogate the learning context (i.e., single sessions, condensed semesters, trimesters, etc.) of individual writing programs and centers in concert with educational strategy use in order to determine tutor-educator behavior and efficacy.

Study Limitations

Analyzing passive data, such as session notes, has limitations such that reporters may fail to include all pertinent information in their records of their tutoring practice or underreport the number of strategies that they use in-session. Tutors may, for example, leave out rudimentary strategies (such as agenda setting—a mainstay in tutoring sessions), as well as ones they attempted but failed to deploy. Likewise, tutors may not have the language to describe or report using strategies they haven’t been trained to enact. However, this model gives us insight into the primacy that tutors placed on specific strategies and what information they privileged and thus chose to include in their notes. Furthermore, analyzing session notes allows us to examine far more sessions than physical observations or recordings of sessions.

Future Research

This is an initial foray into exploring some of the ways in which we might observe and define how tutor-educators engage “flexible” writing pedagogies through empirical modeling. We hope that future studies aim to replicate our study and follow-up with selected participants to interview them directly (Worthy et al.) or conduct cross-institutional research. Because this was a naturalistic experiment, we also hope that researchers amend our study to suit their local context. Should a cross-institutional study on this subject take place, variables such as staffing models, instructor demographics, and training models would need to be streamlined (or controlled for) across institutions to avoid inconsistencies in data and to make fair and consistent comparisons of strategy use across several institutions.

Conclusion

From our assessment, we realized that tutors relied upon particular pedagogical strategies in uneven yet patterned ways. Despite consistent, center-wide training that encouraged tutors to experiment with multiple dozens of strategies, tutors were limited in their uptake regardless of their rank or experience. There are, however, commonly shared strategies that all groups of tutors utilized to some extent, such as point predict, free writing, reverse outlining, grammar modeling, and outlining. However, most tutors over-relied on one strategy and utilized it often in their tutoring sessions.

Our study demonstrates that while the field encourages tutors to be flexible, and tutors indicate a similar desire in their feedback, individual tutors do rely on a limited number of strategies that fit into a repertoire. Variability alone, then, does not indicate flexibility. It may simply indicate tutor imprecision or amiability (i.e., “let’s try this and see what happens” or “well you asked for X so let me give you X”). Therefore, we do not believe that flexibility can be identified, as we initially hypothesized, by the average number of strategies that tutors used per session, or by tutor engagement with unique strategies throughout their tenure at the center. Instead, it might be measured through how individual tutors align by groups of strategies as our study shows.

If we were still at the Ohio State Writing Center (we have both left the institution), we would share these findings with tutors—along with the grouped strategies—as a springboard into discussion where tutors are invited into their data and offered the opportunity to do “self-work” around their tutoring practices (what strategies they use often, which ones they do not use, and ways to develop responsive pedagogy). We would not, however, encourage one group of strategies over another but provide space for exploration and reflection. This kind of assessment-informed training would emphasize curiosity and multiplicity in not only learning new strategies but, also, learning more about situations where tutors feel more or less confidence in their pedagogical training, which, we ultimately think, drove much of the conversation around flexibility in our former center. Using findings from our empirical research, then, one can build an intentional educational model that offers tutors entry into the data, such as the bounded sets of strategies, which they can learn and apply to their work but, also, space to reflect on confidence, anxiety, and preparation for the work.

More research can help us understand how and why writing tutor-educators develop and eventually settle on their pedagogical repertoires, as well as some of the challenges tutors face in novel settings, which has implications for how administrators responsively and holistically prepare their staff for the job. While providing robust training is critical for developing one’s pedagogical approach, there are likely many other factors (e.g., preference, comfort, convenience, resources) that impact the decisions that tutor-educators make about their pedagogical approaches. Labor concerns also heavily factor into how they engage in their work. For the moment, however, this connection between precarity and praxis has not yet been studied, nor has how paraprofessionals developed their pedagogy and applied their training in different educational contexts (e.g., applying tutor praxis in course instruction and vice versa). We know that training does have an impact—tutors are, after all, breaking down into groups that use consistently patterned combinations of strategies and many report anecdotally to us years later that their training helped them in their careers, especially in teaching work—but we believe that there are other external factors that influence their practices that need to examined further.

The Praxis-Specific Upshot of our Findings

Our study found that the field needs to further define and assess what is meant by tutor-educator flexibility. One possibility is to move away from the concept of flexibility altogether as this approach might signal a non-deliberate process that disallows tutor-educators from making intentional choices about their pedagogy in favor of placing primacy on learner need and comfort. While tutoring ought to be collaborative, as Harris noted many years ago (1985), the tutor’s identity and pedagogical praxis should, as Grimm notes, also be considered. For example, perhaps tutors over-relied on specific and limited tutoring strategies because of the sheer volume of tutoring work they were conducting annually (~300–450 hour-long appointments) in addition to other academic and personal obligations. In other words, despite best intentions, they had little bandwidth to add “another thing” to their repertoire. Well-meaning and pedagogically up-to-date training models, then, might not be effective for all populations of writing tutor-educators, particularly time-strapped and under-resourced graduates and other contingent workers. Instead of a lock-step training model, then, we ought to encourage tutors to find their unique (though patterned) educational practices through more curated and modest professional development that is scaffolded and perhaps lingered over (e.g., spending a year on contemplative practices).

We also suggest a set of interventions for practitioners and writing program administrators to support further discussion and exploration on the topic of flexibility and its relationship to pedagogical identity and approach. For practitioners, engaging in reflective practice can encourage deliberate exploration of one’s personal tutoring and teaching practices.

Below are a set of questions for guided self-exploration:

Which strategies or pedagogical approaches do I find myself returning to regularly

What is one strategy or practice I have not yet tried?

What prevents me from experimenting with different pedagogies in my sessions/courses?

How might my program support me in trying a new strategy or practice?

After trying something new in the classroom or writing center, how did it go?

What were some outcomes for learners? What were some outcomes for me?

Think back throughout your career—what has influenced your tutoring/teaching practice?

Writing Center and Writing Program Administrators can engage the topic of teacher praxis and flexibility by enacting some of the following programmatic interventions:

Create and distribute pre-and-post personality-type surveys about educational strategy preferences to help tutor-educators conceptualize their practices and how they may align or diverge from training recommendations and program-wide values

Dedicate time to working with your tutors/instructors to create (and revise) their teaching philosophies (and whether or how notions of flexibility factor into them).

Clarify expectations around specific educational practices and priorities through training materials and professional development meetings.

Assess—through interviews, surveys, artifact collection—the most meaningful educational approaches for tutor-educators in your program.

Ask your tutor-educators to do a “strategies swap” where they share a learning strategy and how to apply it in specific educational contexts.

Bring tutor-educators into programmatic decision making by collaboratively revising shared assignments, assessments, learning goals, mission and values statements.

Offer compensation to writing tutor-educators for course re-design, attending pedagogy workshops and conferences, and for books and materials.

Change the review process for merit and promotion to encourage pedagogical experimentation.

Writing administration work so often happens at a distance, especially in large programs, yet it is vitally important to know what our tutor-educators are (and aren’t) doing in their work. This is not for surveillance purposes, but rather for labor-centered care-taking and professional development purposes. Feelings of inefficacy, cynicism, and physical/emotional exhaustion in the workplace can lead to burnout (Sanchez-Reilly et al.), which can, in turn, lead to any number of personal and professional issues, including work-related stress and attrition. Understanding how our tutor-educators engage with training, and how they experience their work, can be part of a responsible and supportive workplace ecology. Therefore, exploring with your tutors and instructors how they understand, define, and enact flexibility can mitigate a lot of the anxiety over “getting it right” that many experience. It also signals a community-based care system where the expectation is that they have agency in their pedagogical practices and are not only responding to the needs of those around them but, also, to satisfying their intellectual curiosity, their creativity, and their capacity for playfulness and experimentation through their work.

We encourage writing administrators to re-examine their professional development models for their tutors and instructors. Writing Center Directors might start to track and measure the complex processes of strategy selection that tutors navigate. WPAs may review how often the concepts and scholarship they bring to teacher education is taken up through conducting corpus analysis on instructor syllabi and course evaluation forms. And, of course, all writing administrators can simply ask their tutor-educators to reflect on the development of their pedagogical approaches. Are writing tutor-educators “flexible” or are they responsive? Do they take pedagogical risks, and, if not, why? Specifically naming and defining what happens in formal and informal writing education spaces is critical here as this can lead to discussions about revamping professional development models, offering course development compensation, and reimagining evaluation and promotion standards.

Works Cited

Al-Shaer, Ibrahim M. R. “Employing Concept Mapping as a Pre-Writing Strategy to Help EFL Learners Better Generate Argumentative Compositions.” International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, vol. 8, no. 2, 2014, pp 1-29.

Ashton-Jones, Evelyn. “Asking the Right Questions: A Heuristic for Tutors.” Writing Center Journal, vol. 9, no. 1, 1988, pp. 29-36.

Block, Rebecca. “Disruptive Design: An Empirical Study of Reading Aloud in the Writing Center.” Writing Center Journal, vol. 3, no. 2, 2016, pp. 33-59.

Boquet, Elizabeth H. Noise From the Writing Center. Utah State UP, 2002.

Blau, Susan, et al. “Exploring the Tutor/Client Conversation: A Linguistic Analysis.” Writing Center Journal, vol. 19, no. 1, 1998, pp. 19-48.

Burge, Elizabeth, et al. Flexible Pedagogy, Flexible Practice: Notes from the Trenches of Distance Education. Athabasca UP, 2012.

Clark, Irene. “Perspectives on the Directive/Non-Directive Continuum in the Writing Center.” Writing Center Journal, vol. 22, no. 1, 2001, pp. 33-58.

Closser, Bruce. “Somewhere in Space: The Story of One Composition Class’s Experience in the Electronic Writing Center.” The Writing Lab Newsletter, vol. 26, no. 1, 2001, pp. 10-13.

Dennis, Chris, et al. Flexibility and Pedagogy in Higher Education. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 2020.

“Framework for Success in Postsecondary Writing.” Council of Writing Program Administrators, National Council of Teachers of English, and National Writing Project, 2011, pp. 1-10.

Giaimo, Genie et al. “It’s All in the Notes: What Session Notes Can Tell Us About the Work of Writing Centers.” Journal of Writing Analytics, vol. 2, 2018, pp. 226-56.

Gierdowski, Dana. “Instructor Perceptions of a Flexible Writing Classroom.” Flexibility, Sustainability, and the Design of Learning Spaces, edited by Russell Carpenter, Richard Selfe, Shawn Apostel, and Kristi Apostel. CCDigital Press.

Gill, Judy. “Another Look at WAC and the Writing Center.” Writing Center Journal, vol. 16, no. 2, 1996, pp. 164-78.

Gillespie, Paula, and Neal Lerner. The Longman Guide to Peer Tutoring. 2nd ed., Longman, 2008.

Green, McKinley. “Smartphones, Distraction Narratives, and Flexible Pedagogies: Students’ Mobile Technology Practices in Networked Writing Classrooms.” Computers and Composition, vol. 52, 2019, pp. 91-106.

Grimm, Nancy. “New Conceptual Frameworks for Writing Center Work.” Writing Center Journal, vol. 29, no. 2, 2009, pp. 11-27.

Gu, Zuguang, et al. “Complex Heatmaps Reveal Patterns and Correlations in Multidimensional Genomic Data.” Bioinformatics, vol. 32, no. 18, 2016, pp. 2847-49. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btw313.

Hallman Martini, Rebecca. “Reflection: Rebecca Hallman Martini, Founding Editor.” The Peer Review, vol. 4, 2020. https://thepeerreview-iwca.org/issues/issue-4-0/?

Harris, Muriel. “Theory and Reality: The Ideal Writing Center(s).” Writing Center Journal, vol. 5, no. 1, 1985, pp. 4-9.

Hayward, Malcolm. “Assessing Attitudes Towards the Writing Center.” Writing Center Journal, vol. 3, no. 2, 1983, pp. 1-10.

Healy, Dave. “Tutorial Role Conflict in The Writing Center.” Writing Center Journal, vol. 11, no. 2, 1991, pp. 41-50.

Henning, Theresa B. “Theoretical Models of Tutor Talk: How Practical Are They?” Paper presented at Conference on College Composition and Communication, 2001, Denver, CO.

Hitt, Allison. “Access for All: The Role of Dis/Ability in Multiliteracy Centers.” Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, vol. 9, no. 2, 2012, pp. 2-7.

Hobson, Eric H. Wiring the Writing Center. Utah State UP, 1998.

Hung, Hui-Chun, et al. “Applying Educational Data Mining to Explore Students’ Learning Patterns in the Flipped Learning Approach for Coding Education.” Symmetry, vol. 12, no. 2, 2020, p. 213.

Johnson-Eilola, Johndan, and Stuart Selber. “Strange Days: Creating Flexible Pedagogies for Technical Communication.” Journal of Business and Technical Communication, vol. 35, no. 1, 2021, pp. 154-159.

Kirkpatrick, Denise. “Becoming Flexible: Contested Territory.” Studies in Continuing Education, vol. 19, no. 2, 1997, pp. 160-173.

Kirkpatrick, Denise. “Flexibility in the Twenty First Century: Web 2.0.” Flexible Pedagogy, Flexible Practice: Notes from the Trenches of Distance Education, edited by Elizabeth Burge, Chere Campbell Gibson, and Terry Gibson. Athabasca UP, 2012, pp. 19-28.

Li, Li. “Developing Expertise and In-Service Teacher Cognition.” Social Interaction and Teacher Cognition, pp. 104-134. Edinburgh UP, 2017.

Lillge, Danielle. “Uncovering Conflict: Why Teachers Struggle to Apply Professional Development Learning About the Teaching of Writing.” Research in the Teaching of English, vol. 53, no. 4, 2019, pp. 340-62.

Mackiewicz, Jo, and Isabelle Thompson. Talk About Writing: The Tutoring Strategies of Experienced Writing Center Tutors. Routledge, 2018.

Miley, Michelle. “Mapping Boundedness and Articulating Interdependence Between Writing Centers and Writing Programs.” Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, vol. 16, no. 1, 2018, pp. 75-87.

Miller-Cochran, Susan, and Stacey Cochran. “From the Guest Editors: Advocating for Writing and Well-Being.” Composition Studies, vol. 50, no. 2, 2022. https://compstudiesjournal.com/current-issue-summer-2022-50-2/

Newkirk, Thomas. “The First Five Minutes: Setting the Agenda in a Writing Conference.” Writing and Response: Theory, Practice, and Research, edited by Chris Anson. NCTE Press, 1989, pp. 317-33.

North, Stephen. “The Idea of a Writing Center.” College English, vol. 46, no. 5, 1984, pp. 433- 46.

North, Stephen. “Revisiting ‘The Idea of a Writing Center.’” Writing Center Journal, vol. 15, no. 1, 1994, pp. 7-19.

Pinheiro, Jose, et al. nlme: Linear and Nonlinear Mixed Effects Models. R package version 3.1-140, 2019, https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=nlme.

Sanchez-Reilly, Sandra, et al. “Caring for Oneself to Care for Others: Physicians and Their Self-Care.” The Journal of Supportive Oncology, vol. 11, no. 2, 2013, pp. 75-81.

Silvey, Jonathan. The Importance of Flexibility and Adaptability in Writing Centers: Interviews with Three Writing Center Directors. 2014. University of Akron, Master’s thesis. OhioLINK Electronic Theses and Dissertations Center, http://rave.ohiolink.edu/etdc/view?acc_num=akron1396865452.

Silvia, Paul J. How To Write a Lot: A Practical Guide to Academic Writing. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 2007.

Sun, Min, et al. “Shaping Professional Development to Promote the Diffusion of Instructional Expertise Among Teachers.” Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, vol. 35, no. 3, 2013, pp. 344-69.

Thompson, Isabelle. “Scaffolding in the Writing Center: A Microanalysis of an Experienced Tutor’s Verbal and Nonverbal Tutoring Strategies.” Written Communication, vol. 26, no. 4, 2009, pp. 417-53.

Thompson, Isabelle, et al. “Examining Our Lore: A Survey of Students’ and Tutors’ Satisfaction with Writing Center Conferences.” Writing Center Journal, vol. 29, no. 1, 2009, pp. 78-105.

Trosset, Carol, et al. “Learning from Writing Center Assessment: Regular Use Can Mitigate Students’ Challenges.” The Learning Assistance Review, vol. 24, no. 2, 2019, pp. 29-51.

Van Waes, Luuk, et al. “Learning to Write in an Online Writing Center: The Effect of Learning Styles on the Writing Process.” Computers and Education, vol. 73, 2014, pp. 60-71.

Worthy, Jo, et al. “‘What If We Were Committed to Giving Every Individual the Services and Opportunities They Need?’ Teacher Educators' Understandings, Perspectives, and Practices Surrounding Dyslexia.” Research in the Teaching of English, vol. 53, no. 2, 2018, pp. 125-48.

Zuidema, Leah, and James Fredricksen. “Resources Preservice Teachers Use to Think About Student Writing.” Research in the Teaching of English, vol. 51, no. 1, 2016, pp. 12-36.

Appendix A: Family (Grouped) Codes by Individual Strategy Type

*Indicates strategies that fall into multiple classifications

Bold indicates strategies most frequently used across tutor groups

Consultant Strategies List

Reading Strategies (RS):

Read Aloud (RA)

Read Silently (RS)

Point Predict (PP)

Talking Strategies (TS):

Dictation (D)

Discussion (Dis)

Brainstorming (B)

Non-Directive (ND)/questioning

Motivational Scaffolding (MS)*

Reverse Outlining (RO)*

Translingual (L1)

Writing Strategies (WS):

Pre-Writing (Pre)

Free Writing (FW)

Outlining (O)

Sentence Diagramming (SD)*

Paragraph Tracking (PT)*

Revision (R)

Note Taking (NT)

Reverse Outlining (RO)*

Kinesthetic Strategies (KS):

Concept Mapping (CM)

Whiteboard (drawings)

Visual strategies (VIS) such as (post-it note strategy or color coding writing, etc.)

Paragraph Tracking (PT)*

Grammar Strategies (GS):

Patterns of Error (PoE)

Sentence Diagramming (SD)

Direct Instruction (DI)

Revision (R)

Modeling (M)

Planning and Goal Setting Strategies (PS):

Agenda Setting (AS)

Revision Plan (RP)

Planning (P)

Meta-cognitive Strategies (MC):

Knowledge Transference (KT)

Threshold Concepts (TC)

Cognitive Scaffolding (CS)

Audience Awareness (AA)

Skills teaching (i.e., how to take notes) (ST)

Motivational Scaffolding (MS)*

Other Strategies (OS):

Unclear strategy application

Appendix B: Semesterly Training Topics Spring 2019

Newbie Training (University Policies, On-Boarding to Writing Center space and practices)

Accountability and Goal Setting with Clients

Client Report Form Training

Emergency Management

Finding and Developing your Tutoring Practice

Case Studies/Mock Tutorials

Tutoring in specific spaces/media: Walk-in, Synchronous and Asynchronous Online, Writing Groups, High School Community Writing Center

Writing Center “Spiel” Review for Workshops and In-Class Visits

Emotional Negotiation

Code Switching

Libraries/BEAM

Working with Graduate Student Writing

Working with Multilanguage Writers

Working with Instructor Feedback

Wellness and Self-Care in the WC

Conducting Research in the WC

Strategy of the Month (including concept mapping, outlining, point predict)

Tutoring 3000: Additional Tutoring Methods (e.g., concept mapping, scaffolding, grammar, revision strategies like reverse outlining, etc.)