Praxis: A Writing Center Journal • Vol. 23, No. 2 (2026)

Assessing the Field: Establishing the Ethos of Writing Center Publications

Joseph Cheatle

Oxford College of Emory University

joseph.james.nefcy.cheatle@emory.edu

Abstract

This study examines four journals in writing center studies—WLN: A Journal of Writing Center Scholarship, Writing Center Journal, Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, and The Peer Review—to establish their distinct profiles and ethos within the field. Through IRB-approved methods, including a rhetorical analysis of journal websites, systematic review of articles published, and written interviews with editors, this work identifies how each journal positions itself for different audiences and purposes. Findings reveal significant variation in article length requirements, research methodologies, and accessibility for emerging scholars. While WCJ emphasizes rigorous social sciences research, WLN prioritizes practical applications, Praxis focuses on practitioner voices, and TPR supports collaborative mentorship. This analysis provides guidance for practitioners and researchers seeking appropriate venues for reading and publication while illuminating broader trends in writing center scholarship.

Administrators, tutors, practitioners—from novice to expert—often want to know what they should read and where they should publish in the field of writing center studies. New practitioners may want to know where they should start reading about writing centers, including understanding more about the audience, practices, and policies of the journals in the field. Some journals feature more accessible works (in terms of length, previous knowledge of the field, and modality) than others. Meanwhile, researchers may want to determine the best avenue for the publication of their work. While all avenues of publication are open to all researchers, some publications are better suited to specific research and writing than other publications, as each journal has carved out a unique approach to the field. Therefore, this work reflects on the journals in writing center studies to determine their profile and ethos.

Reflecting back on the work of a journal (and the field) is not new. In fact, there are others who have done this type of work as a way to learn more about a specific journal or the field of writing center studies. For a journal, it often occurs when there is a change of editors, to answer a specific question about a journal, or to examine a series of articles from different journals on the same subject. In fact, some of these types of reflections appear in the journals reviewed in this article, including Dana Driscoll and Sherry Perdue’s (2012) “Theory, Lore, and More: An Analysis of RAD Research in The Writing Center Journal, 1980-2009” published in Writing Center Journal; Yanar Hashlamon’s (2018) “Aligning the Center: How We Elicit Tutee Perspectives in Writing Center Scholarship” in Praxis: A Writing Center Journal; the reflections of the outgoing editors of The Peer Review in 2020; and Havva Zorluel Ozer and Jing Zhang’s (2021) “The Response to the Call for RAD Research: A Review of Articles in The Writing Center Journal, 2007-2018” in Writing Center Journal. There are a lot of benefits from looking back at journal articles—these studies help tell us how journals were oriented in the past, including what type of articles they publish and the type of research they focus on. Furthermore, reviewing journals help us identify patterns and trends in the field that are important to practitioners and scholars alike.

This article elects to study the primary journals of writing center studies, including WLN: A Journal of Writing Center Scholarship (frequently referred to as WLN and previously known as the Writing Lab Newsletter); The Writing Center Journal (also known as Writing Center Journal or WCJ); Praxis: A Writing Center Journal (frequently referred to as Praxis); and The Peer Review: A Journal of Writing Center Practitioners (also known as TPR). The goal of this work is not to pass judgment on the quality, practices, policies, and publications of each journal but, rather, to discern how each journal positions itself in the field. To help ascertain the profile and ethos of each journal, this work looks at public-facing aspects of the journal (like the website), previous issues (like the founding issue or other seminal works in their history), written interviews with journal editors, and a review of previously published articles. In the next section, I provide an overview of the research methods used in this work. I then individually examine each of the four journals included in this work in order of the year they were founded (WLN, WCJ, Praxis, and then TPR). I provide an overview and analysis of each journal, as well as research on the articles published from a recent ten-year period in order to determine what types of work are published in each journal. In the conclusion, I put these journals in conversation with each other and offer areas of future research and study. Collectively, these journals highlight the broad variety of publications in the field and how each caters to different audiences and readers while also highlighting different types of research and writing.

Methods

This study uses IRB approved research procedures, including a rhetorical analysis of the website of each journal, a systematic analysis of articles, and written interviews with an editor from each journal. I first conducted a rhetorical analysis of the website for each journal to determine how the journal is publicly positioned and how documents provided by the journal (like a mission statement, reviewer instructions, or submission guidelines, among others) contribute to its ethos. I originally examined each journal’s website before June 2025, and they may have changed since that time. In my examination of recent publications, I focus on journal articles because they form a common denominator among the four journals. While each journal publishes other genres of writing (e.g. TPR publishes “Conversation Shapers,” WLN publishes a “Tutors’ Column,” Writing Center Journal publishes “Provocations,” and Praxis publishes “Columns”), each features scholarly articles. Furthermore, articles are frequently peer reviewed rather than selected only by the editor(s). And, articles comprise the largest component of each publication, taking up the most space in each issue.

Each journal is systematically analyzed over a ten-year period for just the articles they published—rather than other types of work unique to each journal. For WLN, WCJ, and Praxis, I looked at 2015-2024; meanwhile, for TPR, I looked at 2016-2025. The reason TPR is not looked at over the same years as the other journals is because it did not publish any articles in 2015 and 2016. In a systematic way, I attempted to answer the following questions about each journal:

Are articles primarily individually authored or co-authored?

What kinds of work is published? Is it based on qualitative or quantitative research methods? Mixed methods? Or does it not use a research method?

What is the frequency of publication?

I used coding to determine whether an article’s author(s) used quantitative, qualitative, or mixed methods. I examined abstracts where available, then introductions, and finally, if it was still unclear, I reviewed the work looking for methods or other indications about the research. It was important when coding to define key terms:

Quantitative: Refers to the exploration of numerical data from simple to sophisticated. This form of research can aggregate the data, show relationships among the data, or compare across aggregated data (Coghlan & Brydon-Miller, 2014). Data collection methods include questionnaires, observations, sampling, coding (of structured observations, interviews, etc.), documents, and more. Quantitative research often provides a breadth of information as opposed to in-depth examination of a few instances (Cheatle, 2024).

Qualitative: Refers to the exploration of people and things in their natural settings and the attempt to make sense of those things (Denzin & Lincoln, 2005). This type of research is often referred to as ethnographic or interpretive. Data collection methods include observation, interviews, case studies, and more. Qualitative research often provides a depth of information about a few instances (Cheatle, 2024).

Mixed Methods: Refers to the use of both qualitative and quantitative research methods in a single study or work.

In this work, I make a distinction between research that follows more closely social sciences research versus humanistic inquiry. When reviewing the methods employed by the studies, it was important to consider the intentionality of the author’s use of research methods. Oftentimes, author(s) would use narrative and personal experience, which would not be categorized as a social sciences research method for the purposes of this work. For example, Paula Rawlins and Amanda Arp’s (2023) WLN article “Taking Up Space and Time: How Writing Center Administrators Can Better Support Fat (and All) Tutors” draws on personal narrative but does not frame their work as research or as autoethnographic; therefore, it is not categorized as drawing on a social sciences research method. Meanwhile, some do not state a method in the title, nor do they contain a traditionally titled methods section, like Bethany Mannon’s (2016) “What do Graduate Students want from the Writing Center? Tutoring Practices to Support Dissertation and Thesis Writers.” Further investigation found that the author used both surveys and interviews of graduate students in their work, the research was IRB approved, and the author discussed their methods; therefore, this article was considered a mixed-methods study in social sciences research.

In addition to a systematic review of articles published over a ten year period for each journal, I completed an asynchronous written interview with an editor from each journal. Editors were asked about publishing numbers, editorial issues, and supporting documents (see Appendix). One editor from each journal responded in writing to interview questions. It was important that each journal was represented and that a voice from each journal was heard. In the next four sections, I provide an examination of each individual journal before moving to the conclusion.

Writing Lab Newsletter / WLN: A Journal of Writing Center Scholarship

Basic Information

Founded: 1977

Types of Publications:

Articles—Generally 3,000 words and are peer-reviewed.

Tutor Columns—1,500 words and are not peer-reviewed. These highlight the voices of high school, undergraduate, graduate, professional, and faculty tutors.

WLN also publishes Digital Edited Collections (not a part of the journal, these are book-length works that are edited by guest editors) and a blog (WLNConnect, which is managed by a separate editorial team).

Editorial Board: There are six editors who are writing center professionals representing a variety of different institution types and stages of their careers. There is no set duration for an editorial position and these positions rotate off as needed. New editors are found through a call for editors.

WLN: A Journal of Writing Center Scholarship, has played a circuitous journey in writing center studies. It originally started out as the Writing Lab Newsletter before becoming a journal in 2015 with Issue 40, numbers 1-2. The Writing Lab Newsletter, first published in 1977, was the first attempt to create a community of practice among writing center practitioners. Well before the internet, the original issues were typed and then mailed to members of the writing center community. The newsletter reflects the nascent nature of the field of writing centers. According to the publication, the newsletter solicited “questions, announcements, news, evaluations of some materials you use, suggestions for the format, content, and title of the newsletter, offers to take on projects, requests for some particular bit of information, etc. Our intention is to keep the newsletter brief, useful, and informal” (Harris, 1977, 1). Early issues were concerned, primarily, with announcements and compiling lists of writing center practitioners. The second issue included two evaluation sheets used in the Purdue Writing Lab which asks instructors to evaluate students who have used the lab’s services. As more issues were published, the Writing Lab Newsletter quickly settled on a general format, moving from connecting community to featuring articles.

The shift from a newsletter to WLN: A Journal of Writing Center Scholarship in 2015 (Volume 40, Issue 1-2) reflects the growth and evolution of the publication over time. According to the longtime editor Muriel Harris (also the founding editor), in her “Letter from the Editor,” she writes that this issue “launches our new name, new format, and the new direction in the history of this publication—and perhaps in writing center history as well” (Harris, 2015, 1). For Harris, the new name, format, and direction highlights the new nature of writing centers. When originally conceived, the newsletter started a community from scratch. Now, there is the International Writing Centers Association, conferences and institutes, the internet, and other ways to keep the community connected. With this new reality, Harris felt that the newsletter needed to match it as a journal. However, the journal does keep many of the same characteristics of the newsletter: articles are only 3,000 words while Tutors’ Columns are limited to 1,500 words. The journal is also focused on creating community by inviting “submissions from newcomers, experienced scholars, and tutors from all over the globe. All voices are important in our collaborative world” (“Submission Guidelines”). This is an intentionally global approach that is reflected in the other types of publications sponsored by WLN, including a blog titled “Connecting Writing Centers Across Borders” and digital edited collections.

Up until recently, WLN published five issues per year, each featuring 2-3 articles. More recently, it has published fewer issues each year while still publishing around 3-4 articles per issue. It is a generally standard form of publication that includes an Editor’s Note, articles, and the Tutors’ Column. Every once-in-a-while there may be another type of work published, like a book review or column written by a director. But, overall, there is a consistency of form unmatched in other publications. The journal is hosted on the WAC Clearinghouse website.

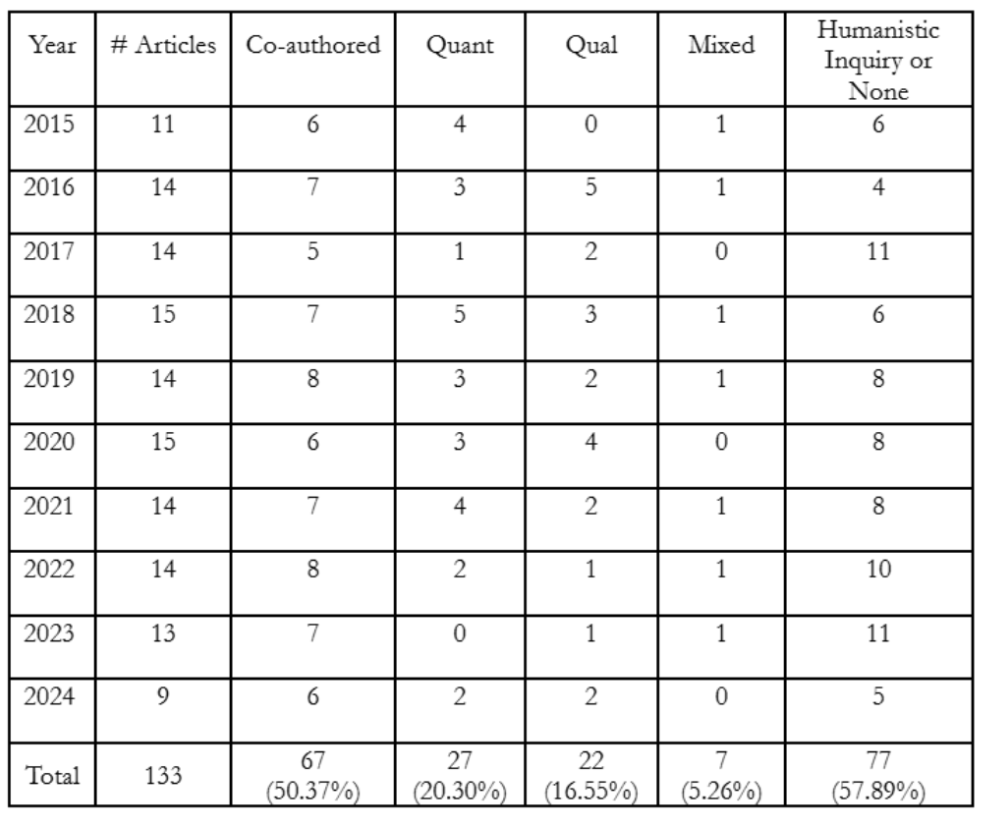

Figure 1 shows articles published by WLN over a recent ten year period (2015-2024) in order to help determine the modern ethos of the journal.

Figure 1. WLN articles from 2015-2024.

WLN is very consistent, publishing five times a year until recently, in 2023, it shifted to publishing four times a year. Each issue contains two to three articles. There was about an equal number of co-authored (50.37%) and single authored works (49.43%), highlighting the parity between the two groups. The majority of the articles (57.89%) did not utilize a social sciences research method; meanwhile, 42.11% used quantitative, qualitative, or mixed-methods research. Of those that used social sciences research methods, 20.30% used quantitative methods, 16.55% used qualitative methods, and 5.26% used mixed methods research. The total amount drawing on quantitative methods is 25.56% while the total amount drawing on qualitative methods is 21.80%. The journal primarily features humanistic inquiry rather than social sciences research.

The short length of articles (3,000 words maximum), the use of Tutor Columns, and the high number of articles that either do not draw on social sciences research or any research at all makes WLN a good journal for novice and emergent authors and readers. These works often require very little prior knowledge of the field and are generally accessible for all readers. According to an editor, “We are open to all topics; however, we do ask for practical takeaways as our readership is often looking for strategies, ideas, or initiatives they can apply to their own centers.” This focus on practical takeaways is important because it builds on the historical ethos of the journal. The WLN editor noted that the historical ethos has “always been to provide a practical resource for writing center professionals and to help build community and conversation within the field.” Despite moves towards supporting authors (through a multi-step peer review process) and addressing important issues in the field (such as disability justice, multilingualism, and integrating reading into writing center pedagogy), the journal maintains an historical focus on the practical tools of tutoring and administration while maintaining accessibility for all writing center practitioners.

WLN operates with an ethos rooted in accessibility, practical application, and inclusive community building within writing center scholarship. The journal maintains an approach that welcomes all voices—from newcomers to experienced scholars to tutors at all levels—reflecting the journal founder’s belief that writing knowledge emerges from community rather than hierarchical expertise. This inclusive ethos is operationalized through intentionally accessible publishing practices: articles are capped at 3,000 words, many works require minimal prior field knowledge to read, and the journal explicitly prioritizes “practical takeaways” that practitioners can immediately implement in their own centers. While WLN has evolved from its origins as a grassroots newsletter to a more formalized journal, it has consciously preserved its foundation of serving as a practical resource that connects writing center professionals and tutors across institutional contexts. The journal’s research profile—with nearly 58% of articles employing humanistic inquiry rather than social sciences research methods—further reinforces its commitment to valuing experiential knowledge and reflective practice alongside traditional academic scholarship.

Writing Center Journal

Basic Information

Founded: 1980

Types of Publications:

Front Matter—Documents include submission guidelines, names of reviewers, and an introduction from the editors.

Articles—6,000-10,000 words.

Provocations—2,000-3,000 words in length, these works are meant to provoke the audience to think more about a specific topic and start a dialogue in the field.

Book Reviews—Short reports about recently published works in the field.

Back Matter—Announcements and other information.

Editorial Board: During the past four editorial teams, there have been three editors per team. The editors tend to be tenured faculty, although there have been junior faculty and administrative/professional editors in the past. Editors are generally active members in the field with a history of publishing. Editorial teams change every 3-5 years.

The Writing Center Journal was launched in 1980 by Lil Brannon and Stephen North and remains the flagship journal in the field of writing centers, and one of two journals sponsored by the International Writing Centers Association. It was the second publication founded, after the Writing Lab Newsletter, meant to connect the writing center community. It was also created as a way to professionalize the field and align it more closely with the broader field of composition; the journal is a culmination of the maturation process of writing centers and recognition that writing centers have become part of the academic establishment and an important service to students, faculty, and staff.

The “Editorial Policy” of the first issue published lays out the broad scope of the journal. The policy states that, “The Writing Center Journal publishes articles dealing with all aspects of writing center instruction from pedagogical theory to administration, from formal research to practical tutor training.” The original editors, Lil Bannon and Stephen North, envisioned the journal as focusing on three types of work. The first is essays that are primarily theoretical, that “explore or explain the ways of writing center instruction” (Brannon and North, 2). The second is articles connecting theory with practice. And the third is essays that draw upon experience in writing center teaching and administration and offer insights that others in the field can use. Within this same issue, the editors note that the third type of work—those based on personal experience—were the bulk of articles they were receiving for submission and wanted to change that to focus on more theoretical works and those connecting theory with practice.

Brannon and North envisioned the journal filling a gap in the field of composition while also connected to the broader field of composition. They write,

As scholars, as teachers and researchers in composition, we recognize in writing center teaching the absolute frontier of our discipline. It is in writing centers that the two seminal ideas of our reborn profession operate most freely: the student-centered curriculum, and a central concern for composition as a process. And it is in these centers that great new discoveries will be, are being, made: ways of teaching composition, intervening in it, changing it. Writing centers provide, in short, opportunities for teaching and research that classrooms simply cannot offer. The Writing Center Journal fills the need for a forum that can report on and stimulate such work. (Brannon and North, 1)

By positioning the journal on the frontier of the field of composition, Brannon and North claim to be on the cutting edge of innovation and pushing the boundaries of what is possible in composition. Furthermore, they view the journal, and the field, as student-centered and addressing composition as a process (and not just as a product).

A current editor situates the ethos of the Writing Center Journal within their view of it as the flagship journal of the International Writing Centers Association. The editor quotes from the WCJ website to point to the modern ethos of the journal,

This academic peer-reviewed journal of scholarship intersects with writing centers in a wide-range of institutional contexts. WCJ values innovative research from a diversity of theoretical and methodological approaches, and it seeks to publish emerging voices that challenge the status quo and that represent the plurality of identities and languages that happens in and around writing centers, whether at research universities and colleges, 2-year colleges, HBCUs, HSIs, tribal colleges, trade and professional schools, or community-based literacy and writing projects.

The editor noted that while the current editorial team still adheres to the traditional ethos of the journal—“to publish strong research in writing centers to advocate for the rich work that happens in these spaces”—they are also committed to publishing new voices and broadening the readership of the journal. Additionally, the editor cited the fact they recently moved the journal to open-access and online as a way to create more opportunities for people to access and read the journal. The editor also wrote on the future of the journal, stating, “I believe the journal will continue to publish rich and innovative scholarship that challenges the field to think about the work they do in their spaces and inspires us; I also believe new voices and a more diverse group of thinkers/scholars are contributing to writing centers, making the work stronger.” As the editor notes, the future of the journal is in building upon the historical ethos of the journal while recognizing the importance of including more diverse scholars.

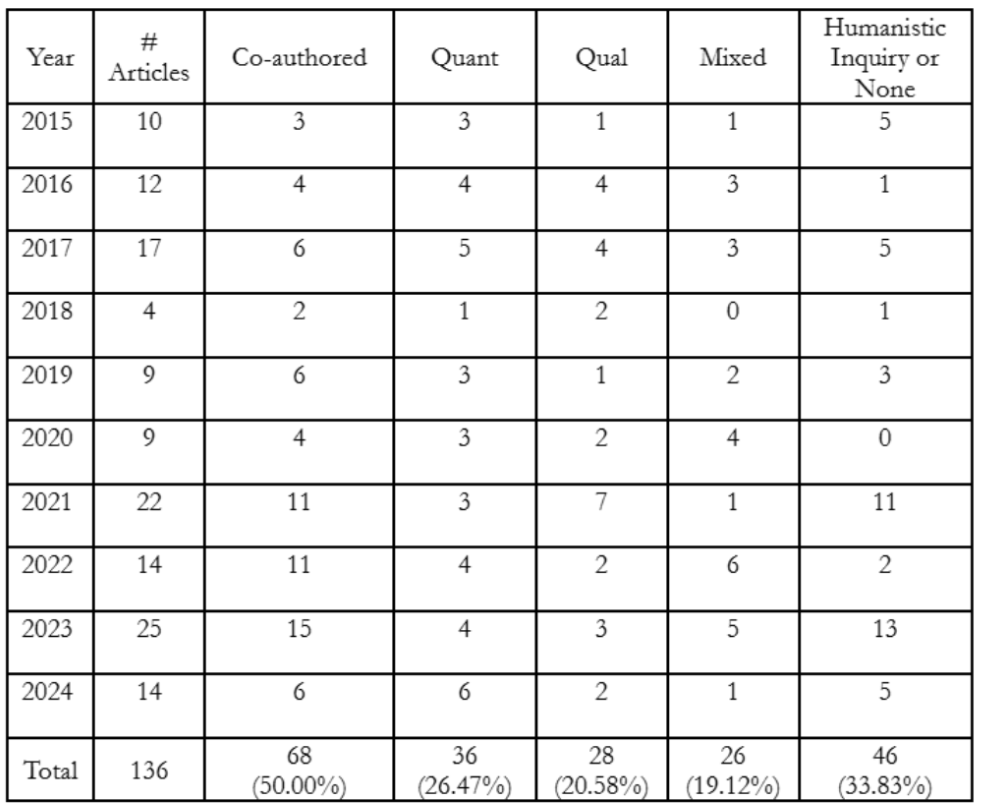

Figure 2 shows articles published by Writing Center Journal over a recent ten-year period (2015-2024) in order to help determine the modern ethos of the journal.

Figure 2. WCJ articles from 2015-2024.

There are an equal number of articles published featuring solo authors and co-authored. The use of social sciences research methods in published articles was high for the Writing Center Journal. Of the articles published, nearly two-thirds (66.17%) used either quantitative, qualitative, or mixed research methods. Meanwhile, 33.83% either did not utilize research methods in their work or drew on humanistic inquiry. One finding of note is that more articles not using social science research methods were published in the last few years. Among those featuring social science research methods, 45.59% were quantitative while 39.70% were qualitative.

Because it features a high number of articles based on social sciences research, the Writing Center Journal may serve as a barrier for tutors or early career scholars who may not have the knowledge or time to conduct extensive social sciences research-based articles for publication. But, WCJ is mostly opaque in terms of their supporting documents for authors, which can create a sense of mystery for those looking to publish in the venue. For example, they don’t provide significant guidance to authors for navigating the peer review and publication process, which may be an assumption that authors are already familiar with those processes. However, it has recently transitioned to open-access, which allows more readers. While the original editors were concerned that they were receiving too many works based on personal experience, time has shown how the journal has moved from publishing on personal experience to publishing more social science research studies.

The Writing Center Journal sees itself as a prestigious publication in the writing center field, aiming to make writing center work look serious and scholarly to the broader academic world. Founded with the explicit goal of professionalizing the field, the journal maintains an aspirational ethos that views writing centers as “the absolute frontier” of composition, emphasizing innovation, theoretical sophistication, and methodological diversity in its approach to scholarship. The journal strongly values high-quality social sciences research more than personal experience or practical tips. With articles that are, on average, much longer than other journals (over 6,000-10,000 words), it can be more challenging for newer scholars or tutors to publish there. However, the journal is also trying to evolve by including more diverse voices and perspectives, recently making articles free to access online, and welcoming scholarship from a wide variety of institutional and professional contexts. Unlike publications focused on immediate practical application, WCJ prioritizes theoretical contributions and rigorous social sciences research methods, positioning writing center work as a legitimate academic discipline worthy of serious scholarly attention. This creates a journal that serves primarily as a venue for established scholars to share complex research rather than a practical resource for everyday writing center practitioners.

Praxis: A Writing Center Journal

Basic Information

Founded: 2003

Types of Publications:

Focus Articles—Described on the website as “scholarly essays (“focus articles”) on writing-center consulting, researching, administration and training. Focus article submissions may be based on theoretical and critical approaches, applied practices, or empirical research (quantitative or qualitative). Focus article submissions are sent out to our national editorial board for blind review.” The recommended length is 5000-8000 words.

Column Essays—Can be responses to previous articles but can also be less researched, and more heavily autoethnographic or reflective on tutoring. These submissions do not go through the peer-review process and are under 1,500 words.

Book Reviews—Reviews of recently published books in writing center studies that do not go through the peer-review process. Book reviews are generally under 1,500 words in length.

Praxis also published Axis blog posts on their website, which are low-stakes publishing opportunities that undergo internal review and copyediting. These are shorter than an article at 1,500 words and are more autoethnographic or narrative. Posts do not undergo peer review.

Editorial Board: There are three journal editors, including one Executive Editor (the Director of the University Writing Center at the University of Texas) and two Managing Editors who are always graduate students at the University of Texas. The Executive Editor features little turnover while the Managing Editors typically serve for two years.

Praxis: A Writing Center Journal (more informally known as just Praxis) is published by the University Writing Center at the University of Texas at Austin. Founded in 2003, Praxis has been published as a peer-reviewed journal since Fall 2011. Praxis is the third major journal established in the field of writing center studies (after WLN and WCJ) and is centered around the tangible practice of the writing center. This is central to the journal’s identity and is embodied even by its name: “praxis” means “practice, as distinguished from theory.” An examination of the publication’s “Policies,” “Instructions for Authors,” and the articles that its editors choose to publish all reveal its dedication to the actual work done in writing centers, as opposed to more theoretical writings.

The inaugural issue—Volume I, Issue I—sets the tone for the publication. In their “From the Editors,” journal editors write that this is “a new publication devoted to the interests of writing consultants” indicating that they are interested in labor issues, writing center news, training, consultant initiatives, and scholarships (The Editorial Collective 2003). They go on to note that, “We aspire to provide a forum for the voices and concerns of writing center practitioners across the county.” The focus of the journal, they write, is on the practitioner. They state about their name that,

Our title, the Greek word praxis, is typically translated as “practice,” which for writing center consultants denotes both our work with writers and the training we do to prepare for it. Praxis resonates all the more because it connotes practice inextricably entwined with theory—the daily concerns of writing center practitioners. The term, championed by both ancient Greek and contemporary rhetoricians, makes explicit our connection with the field of rhetoric, the basis for much of how we think about writing.

There are a few things to note in their claim. The first is that praxis (practice) is entwined in theory, putting theory into action. Because it is focused on practice, it opens up who can publish in Praxis to a wide variety of practitioners. The second is that the journal is less concerned about the perspectives of theoreticians and administrators outside of practice—it does not make explicit mention of these two groups.

This focus on practitioners—widely defined—is reinforced in the journal’s supporting documents found on its website. Under the sub header “Focus and Scope” on the Praxis “Policies” page, they write, “As a forum for writing-center practitioners, Praxis welcomes articles from writing-center consultants, administrators, and others concerned with issues related to writing-center practices […]” (“Policies”). As a scholarly journal, Praxis does not limit itself to submissions from “traditional” scholars; instead, it encourages works from a wide variety of those involved in the actual day-to-day work of writing centers. Praxis, as a reflection to their welcoming policies, practices an open-access policy, which is important because it lowers the barrier to accessing the journals works—all can access it regardless of their institutions’ ability to subscribe to journals behind a paywall. It also demonstrates the journal’s commitment to increasing accessibility to writing center studies.

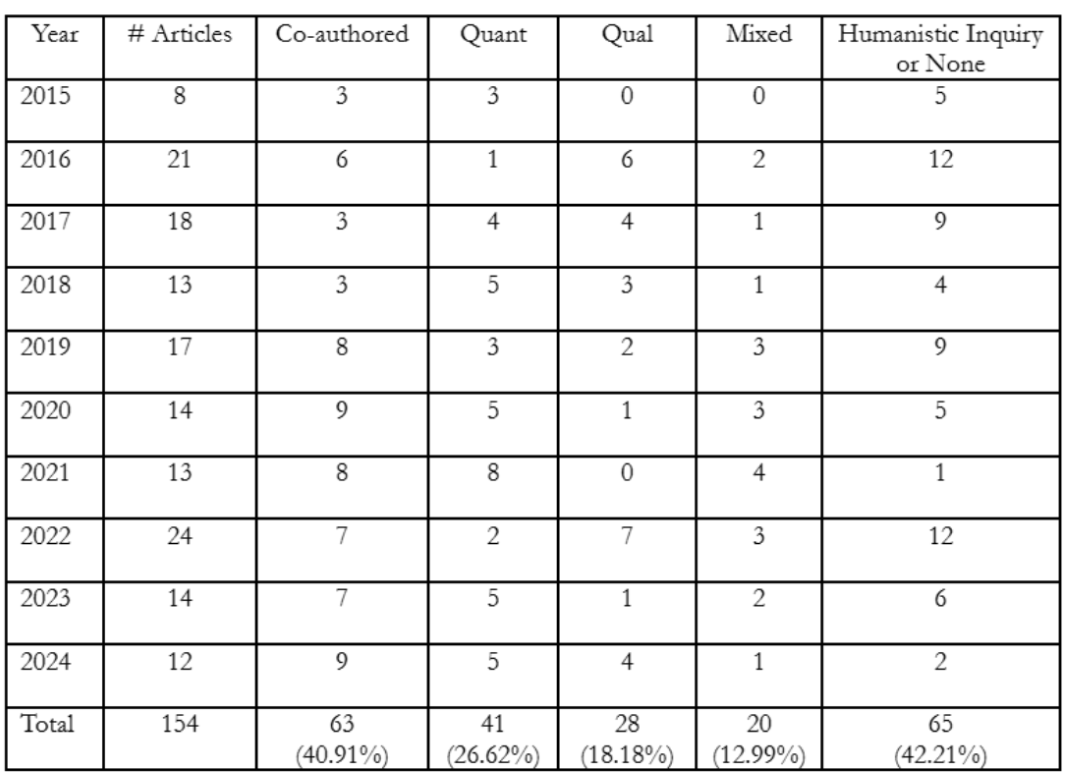

Figure 3 shows articles published by Praxis over a recent ten-year period (2015-2024) in order to help determine the modern ethos of the journal.

Figure 3. Praxis articles from 2015-2024.

There were fewer co-authored articles (40.91%) than articles published by a solo author (59.09%). Among the published articles, 57.79% utilized social sciences research methods while 42.21% did not utilize any research methods or drew on humanistic inquiry. In total, 39.61% drew on quantitative methods while 31.17% drew on qualitative methods. The number of articles published, and the preferred methods, differed each year without a discernible pattern.

According to a Praxis editor, they view the ethos of the journal as “focused on accessible, participatory, and community-focused knowledge making.” Having graduate students as editors allows them, as the editor says, to attend to transparency and issues of labor. This opens up the avenue of publication in Praxis to additional tutors and scholars. There are also pages on the website that help demystify the publishing process and function as resources for authors, including “Policies” and “Instructions for Authors.” The editor goes on to note that, in more recent publication cycles, “[we] received more qualitative and narrative articles than quantitative research. This is reflected in our recently published issues, but not due to editorial preferences regarding type of submission” and “We receive a lot of practice and story-based submissions, followed by lore and theory.” Despite receiving many submissions based on practice, story, lore, and theory, the journal still publishes more articles based on social sciences research.

Praxis operates with an ethos centered on making writing center scholarship accessible and welcoming to everyone doing the work in writing centers, not just traditional academics. The journal’s practitioner-focused approach is reflected in the journal’s name and in the commitment to publishing work that connects real-world writing center experiences with broader ideas. The journal deliberately lowers barriers to publication by providing clear guidance for new authors and making all articles free to read online. While Praxis does publish social sciences-based research articles, it equally values personal stories, reflective essays, and practice-based insights that don’t require formal social sciences research methods. The journal sees itself as a community space where writing center workers can share what they have learned, ask questions, and connect with others doing similar work in the field. Praxis values transparency, accessibility, and the everyday wisdom that comes from working directly with writers. This creates a publication that is an approachable place for tutors and newer scholars to share their voices and experiences.

The Peer Review: A Journal for Writing Center Practitioners

Basic Information

Founded: 2015

Types of Publications:

Articles—7,000-10,000 words in length that undergo peer review.

Conversation Shapers—Projects that help shape the future of writing center research. These projects are a 500-word framing statement that introduces a topic followed by a curated bibliography of 20-25 sources. These works are peer-reviewed.

Tools Demos and Other Multimodal Pieces—These works highlight tools and multimodal pieces reflecting areas of tutoring, learning, and administration in writing centers. These works go through the peer review process.

Book Reviews—Reviews of currently published books in the field of writing center studies. These are not peer reviewed.

Editorial Board: The board features a Professional Editor, Managing Editor, and Web Editor. There are also two to three graduate student editors. Editors change every three years and replacements are found through a call for editors.

The Peer Review was founded by editors Rebecca Hallman and Sherry Wynn Perdue in 2015 and began publishing peer reviewed articles in 2017. According to the founding editors in Issue 0, their vision for the journal was “a peer reviewed, open access, fully online, and multimodal journal to showcase the best scholarship of our field” (Hallman and Perdue 2015). At the time, TPR was the second journal to be fully digital and open access (after Praxis); WLN and WCJ both still included subscription print journals. It was important for the journal to be open-access to intentionally “showcase the work of graduate, undergraduate, and secondary tutors engaged in writing center research” in a way that allows all people to access it (“Submit”). In a description of what they want to publish, the editors note that they want works grounded in theory, framed by the extant literature, supported with data, and presented in a medium that best represents the work. Uniquely, TPR does include multimodal scholarship and research; rather than only accept traditional texts, the journal publishes multimodal works, including demonstrations of technology and software.

The journal focuses frequently on the idea of collaboration, both in the works that it accepts as well as through the peer review process. According to the founding editors, “By placing collaboration at the center of this publication, by modeling it in the editorial structure, and by showcasing it in most contributions to Issue Zero, we seek to challenge the primacy of the single author study penned by a scholar who creates art and science in isolation” (Hallman and Perdue 2015). All but one of the works published in Issue 0 feature multiple authors, and one work is Hixson-Bowles and Paz’s (2015) “Perspectives on Collaborative Scholarship” which lays out an argument for why we do, and should, collaborate. Furthermore, the peer review process is focused on collaboration. Each article that goes out for peer review is assigned a graduate student mentor and reviewers are provided a “Guidelines for Reviewers” that states that reviewers offer “feedback that allows the author(s) to grow and develop throughout the review process” which means that the “goal is to get just about every pertinent submission to publication.” This mentoring model signifies that the journal is looking to publish as many works submitted as possible, electing to work with authors to improve their works rather than rejecting them outright.

TPR’s website includes numerous pages and documents meant to help readers, authors, and reviewers alike. Among the pages and documents are a style guide, accessibility guide, anti-racist scholarly reviewing practices, a guideline for reviewers, a guideline for authors who have gotten feedback, and a policy on author and reviewer use of AI. These pages and documents help to demystify the writing process and reflect the journal’s commitment to publishing undergraduate students, graduate students, and early career scholars who may not have as much experience publishing in an academic journal.

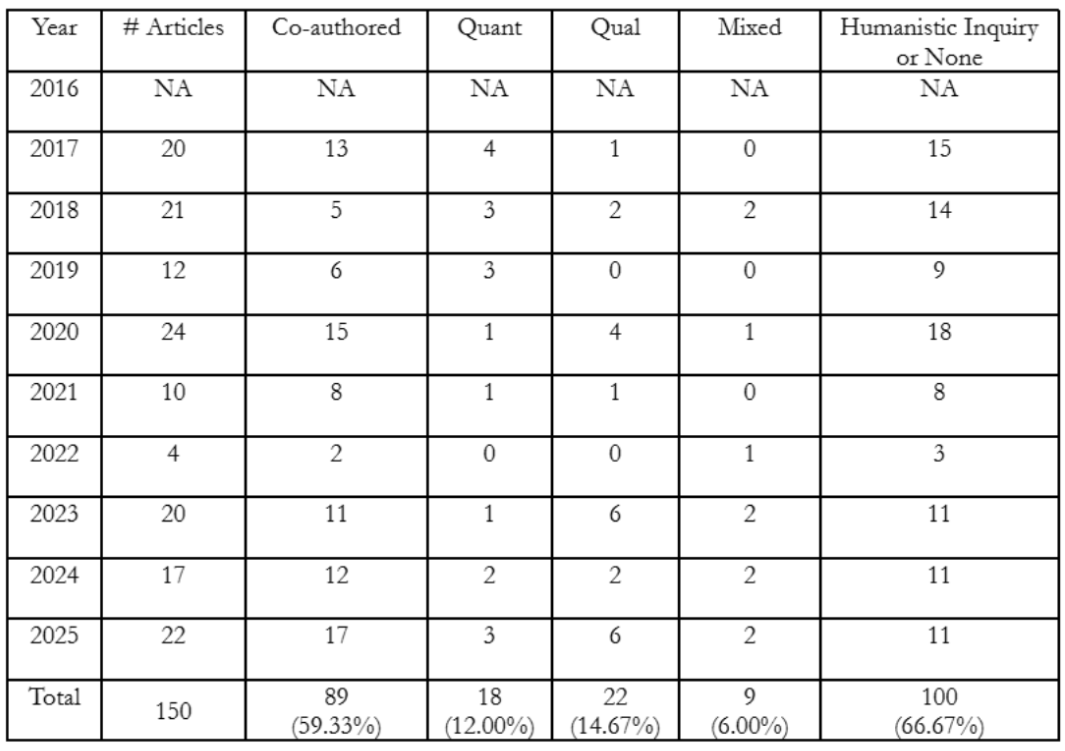

Figure 4 shows articles published by The Peer Review over a recent ten year period (2016-2025) in order to help determine the modern ethos of the journal.

Figure 4. TPR articles from 2016-2025.

The Peer Review published 150 articles in nine years. Despite being founded in 2015, in 2015 and 2016 there were no articles published as the journal elected to publish an issue featuring a series of works highlighting the philosophy and principles of the journal. Of the articles published from 2016-2025, over half (59.33%) were co-authored while 40.33% were solo authored. Most articles, 66.67%, did not utilize quantitative or qualitative methods in their work. Meanwhile, 12.00% used quantitative methods, 14.67% used qualitative methods, and 6.00% were mixed methods. A total of 18.00% were based on quantitative methods while 20.67% were based on qualitative methods. In total, 32.67% of the articles were based on social sciences research while 67.33% were based on humanistic inquiry.

According to one editor, TPR was established to be an alternative journal to those currently established in the field, focusing specifically on students, those new to the field, and emergent scholars. Over time, the editor thinks the journal is “moving more into an established period where we publish pieces not only by newcomers to the field but researchers established and cowriting with undergrads and grads.” There is also a uniqueness about TPR in its incorporation of multimodal and digital works. While the newest journal among those examined for this work, it is open-access, supported by the International Writing Center organization, and increasingly a prominent voice in writing center studies. For those looking to publish, TPR appears to be a supportive journal to authors, particularly because of the resources—like their “Guideline for Reviewers” and “You’ve Gotten Feedback, Now What”—which helps to demystify the peer review and publication process. Additionally, TPR publishes many works that do not draw on social sciences research methods—or that might have been rejected by other journals in the field for being too controversial, as one editor notes—while welcoming a wide variety of works.

TPR operates with an ethos of collaborative mentorship and inclusive innovation, designed specifically to welcome newcomers and emerging scholars into writing center research while pushing the boundaries of what academic publishing can look like. The journal actively works to break down barriers that often exclude students, early-career scholars, and non-traditional researchers from sharing their work. This supportive approach is evidenced in the journal’s mentoring based peer review process, where the goal is to help almost every submission reach publication rather than rejecting work outright, and in the extensive collection of resources that guide authors through every step of the peer review process. TPR is unique for its embrace of digital and multimodal scholarship, allowing authors to present their work through videos, interactive tools, and other forms of technology. The journal values accessibility by making content open-access, providing clear guidance for new authors, and welcoming a broad variety of works. This creates a publication that feels more like a supportive learning community where the focus is on growing the field by nurturing new voices.

Conclusion

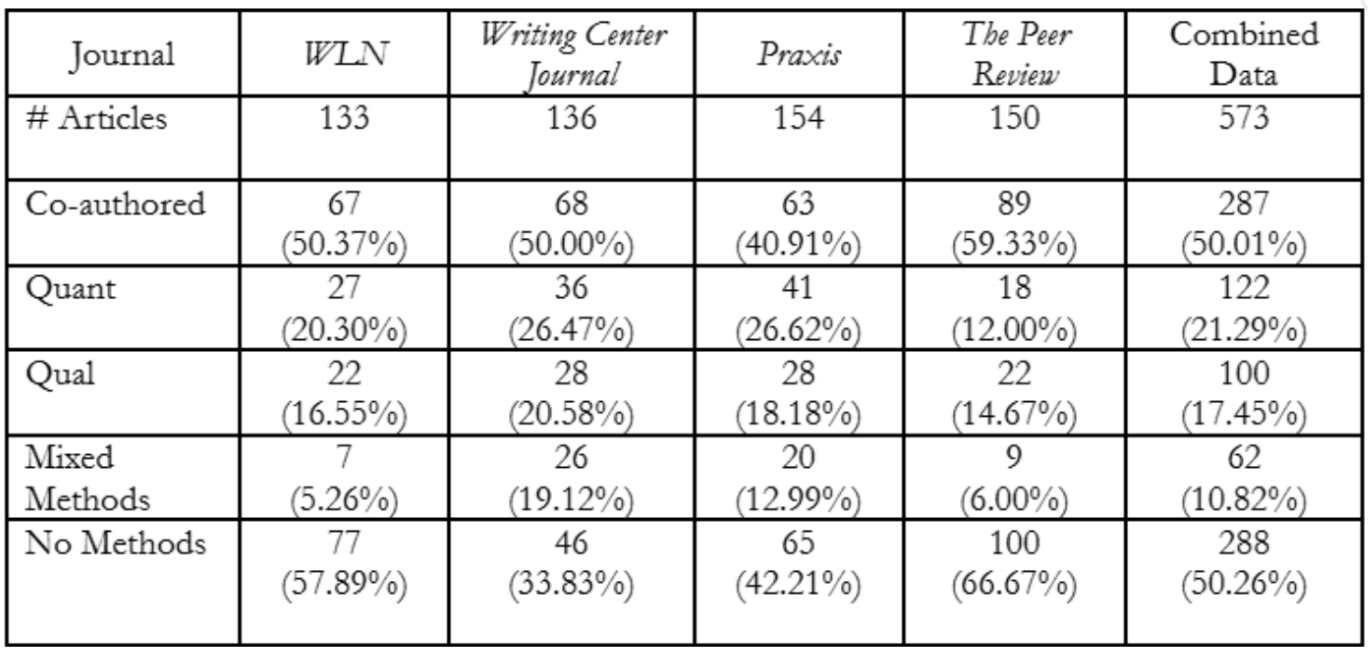

While it is important to consider what the output of each journal says about that journal, it is also helpful to put the data from each journal into relation with each other. Figure 5 features the aggregated data from each journal in order to compare them with each other as well as look at larger trends in the field.

Figure 5. Combined data from WLN, WCJ, Praxis, and TPR.

The first finding that stands out is the number of co-authored publications compared to single-authored publications. As noted in another work that tracked collaborative publications in the Writing Center Journal, “Collaborative Publishing and Multivalent Research: Writing Center Journal Scholarship from 2001 to 2020,” there was a large increase in co-authored works from 2001-2010 to 2011-2020; in fact, there was a 73.91% increase in co-authored works between those times (Cheatle, 2024). Previous research on Writing Center Journal articles highlights a shift from single-authored to co-authored works over time, which tracks with the increase of social sciences research methods. In viewing the combined data above, co-authored works are published around the same level across journals. While Praxis features the least co-authored publications at 40.91%, The Peer Review published the most co-authored works at 59.33%. Meanwhile, co-authored publications for both the Writing Center Journal and WLN were around 50% of works. The near-parity between single-authored and co-authored articles reflects the collaborative nature of much of writing center work.

The second finding that stands out is the use of social sciences research methods versus no research methods or humanistic inquiry in articles by journal. Writing Center Journal publishes more articles that use social sciences methodologies (90 or 66.17%) while Praxis publishes the second most (89 or 57.79%). Meanwhile, The Peer Review and WLN publish the least number and percentage of social sciences research-based articles, at 49 (32.67%) and 56 (42.11%) respectively. There is almost a parity across the journals balancing social sciences research methodologies with works based on humanistic inquiry or not utilizing any research methods. The lack of social sciences research methods in many articles across journals speaks to the continued focus on personal experience, lore, and observation in the field.

The third finding that stands out is that Writing Center Journal and Praxis publish the most quantitative-based articles at around 26% of works. They also published the highest percentage of qualitative-based articles, at 20.58% and 18.18% respectively. And, they published the highest percentage of mixed methods works at 19.12% for Writing Center Journal and 12.99% for Praxis. Meanwhile, The Peer Review and WLN published the fewest percentage of articles based on quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods studies. The Peer Review and WLN published a significantly lower number of quantitative-based articles at 12.00% and 20.30%. When the journals are combined, this data helps us think about the field collectively, particularly what research is done in writing centers, what type of scholarly works are valued, and potential barriers to publishing.

While this work provides a profile of four major journals in the field of writing center studies, it functions only as a starting point to future research projects on the topic of writing center journals and their identity/ethos. Future researchers could look at changes to the journals, individually and collectively, over a longer period of time. There are also opportunities to research the topics the journals published on to see how they changed over time or are unique to each journal. Additionally, because the websites and submission portals of each journal changes over time and across editors, researchers can examine these changes and how they reflect the changing journal landscape. And, researchers may want to include additional journals in the field to this study, including the Dangling Modifier and SDC: A Journal of Writing Center Studies. There may even be opportunities to use a corpus analysis of titles or even texts as a further avenue of study. Considering the amount of research still to be done in this area, I encourage others to explore these rich, and important, topics.

References

Bannon, Lil and North, Stephen. 1980. “From the Editors.” Writing Center Journal 1(1): 1-3.

Cheatle, Joseph. 2024. “Collaborative Publishing and Multivalent Research: Writing Center Journal Scholarship from 2001 to 2020.” Writing Center Journal 42(3): 50-73.

Coghlan, D., & Brydon-Miller, M. 2014. The Sage Encyclopedia of Action Research. Sage Publications.

Denzin, N., & Lincoln, Y. 2005. The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research. SAGE.

Driscoll, Dana Lynn and Perdue, Sherry Wynn. 2012. “Theory, Lore, and More: An Analysis of RAD Research in The Writing Center Journal, 1980-2009,” Writing Center Journal: (32)2: 11-39.

“Editorial Policy.” 1980. Writing Center Journal 1(1).

“Guidelines for Reviewers.” Nd. The Peer Review. https://thepeerreview-iwca.org/about/guidelines-for-reviewers/

Hallman, Rebecca and Perdue, Sherry Wynn. 2015. “Editors’ Introduction.” The Peer Review.

Harris, Muriel. 1977. “We Are Launched!” Writing Lab Newsletter (1)1: 1.

----. 2015. “Letter from the Editor.” WLN: A Journal of Writing Center Scholarship 40(1-2): 1-3.

Hashlamon, Yanar. 2018. “Aligning With the Center: How We Elicit Tutee Perspectives in Writing Center Scholarship.” Praxis: A Writing Center Journal 16(1).

Mannon, Bethany. 2016. “What do Graduate Students Want from the Writing Center? Tutoring Practices to Support Dissertation and Thesis Writers.” Praxis: A Writing Center Journal 13(2).

Ozer, Havva Zorluel, and Jing Zhang. 2021. “The Response to the Call for RAD Research: A Review of Articles in The Writing Center Journal, 2007–2018.” The Writing Center Journal (39)1-2: 233–60.

“Policies.” Praxis: A Writing Center Journal. https://www.praxisuwc.com/policies

Praxis Editorial Collective. 2003. “From the Editors.” Praxis: A Writing Center Journal.

Rawlins, Paula, and Arp, Amanda. 2023. “Taking Up Space and Time: How Writing Center Administrators Can Better Support Fat (and All) Tutors.” WLN: A Journal of Writing Center Scholarship 47(3): 19-26.

“Submission Guidelines.” WLN: A Journal of Writing Center Scholarship. https://wac.colostate.edu/wln/submission-guidelines/

“Submit.” 2015. The Peer Review.

Appendix

Interview Questions for Journal Editors

Topic: Publishing Works

What types of works (tutors column, conversation shaper, book reviews) are published? Please describe each briefly.

What are the general ranks (undergraduate student tutor, graduate tutor, professional, administrator, tenure-track, etc.) of the authors published? (if that can be determined)

What types of articles are generally accepted for submission? (quantitative, narrative, qualitative, etc.).

Is there a preferred topic (theory, practice, lore, stories, etc.) of article submission? If so, what is it?

Topic: Editorial Issues

How many editors are there for the journal?

What is the makeup of the editors?

Is there an advisory board?

Are there any other supporting personnel?

How often do editors change at the journal?

What is the process for changing editors?

Topic: Supporting Documents

What supporting documents does the journal website provide (ie. mission statement, formatting guide, rules for reviewers, etc.)? How do you decide which documents to include?

Topic: Ethos

What do you believe is the historical ethos of the journal?

Has the ethos of the journal changed over time? If so, how?

What is the current ethos of the journal?

What do you believe is the future of the journal?