Praxis: A Writing Center Journal • Vol. 22, No. 3 (2025)

Coming to Terms: A Quantitative Analysis of Naming Conventions in and of United States Writing Centers

Abraham Romney

Idaho State University

abrahamromney@isu.edu

Abstract

Terms used to describe writing support workers in higher education, as well as the location of their employment have sparked a long history of debate in writing center studies but have led to only scattered empirical research. The author examines the history of this debate addressing connotations of various terms and then aims to verify actual naming practice. The present study investigates the impact such debates have had on writing center practice by assessing public web pages from 575 university writing centers to see what terms are generally employed. The study shows that “writing center” is the most popular name for the location of writing tutorial services and that “tutor” remains the most popular term. This finding suggests that “center” has won out over other terms, but the popularity of “tutor” is much less decisive. At institutions with higher enrollment, in R1 institutions, and in the case of graduate student employees, the use of the term “consultant” increases. The general prevalence of the “writing tutor” and the rise of the more recent “writing consultant” and other variants may suggest a lag between scholarly critique and writing center practice, but it could also derive from institutional context. Alternative tutor terms could be employed, but an empirical study of efficacy would be needed to move naming from the realm of lore and conjecture.

Introduction

Debates over the titles used to describe both workers and workspace for writing support have been a staple in writing center studies because, it has been argued, these terms shape both the kind of work we can do and the perception of that work by stakeholders and those who use the services [1]. In 1990 Lex Runciman suggested that writing centers drop the term “tutor” altogether because it had too many remedial connotations, objecting to both referring to staff as tutors and to referring to the center as a “tutorial facility” (27). Scholars have covered the transition from terms like “writing lab” to the ubiquitous “writing center” (Lerner), but other names and configurations exist for spaces in which auxiliary support for student writing takes place via conferences, sessions, consultations, or tutorials. Often behind the arguments for particular titles lie assumptions about the value and perception of those terms, occasionally with the sense that changing the name will have a significant impact.

Certainly, names can affect the scope and perception of services as was the case for centers changing from a “writing center” to a “multiliteracies center” (Balester et al., n.d.), a term that could point to new directions and commitments (Romney and Kitalong). Names used for tutors, however, do not always carry their own obvious meaning and are usually borrowed from other domains. One recent study in business management suggests that “human capital” can benefit from a sense of agency and creativity and can better cope with emotional exhaustion if given flexibility in choosing their own titles, but whether or not that translates to external perception is murkier (Grant, Berg, and Cable). Though the way a term is used depends on local perception, professional job titles and names for writing centers are rhetorical and can establish expectations of power, authority, knowledge, and duty and can signal relationship boundaries between clients and workers, influencing interactions and outcomes. As Cheatle and Bullerjahn point out though, it can be difficult to change undergraduate perceptions despite efforts to promote more expansive views of the work we do (25).

Despite a lack of empirical evidence of the actual effects of titles, the prevalence of debates over appropriate titles suggests that, largely, the field has taken to the assumption that the terms we use to describe a writing center workforce and the names we use to describe the space of a center has some effect on the type of work we do. At the very least, the names we choose do become part of the public face of our centers. Emily Isaacs and Melinda Knight, who undertook a study of writing center websites, suggest that writing center directors should be “vigilant in their work of developing a public face that projects writing centers in terms of what they do now, and also aspirationally” (59-60). In his dissertation, Scott R. Sands looks at the terms we use as metaphors that shape the way that we view tutoring, metaphors that can both highlight and obscure the work that tutors do [2].

Contested Terms

Scholars arguing for changes in terminology have generally aimed to improve communication about what work is actually done in writing centers and to more effectively get students through the doors. Institutionalized peer tutoring first came about in the late 1960s (Boquet, 474), which may have given rise to some of the unease with “tutor.” Many have pointed to the inherent (perhaps oxymoronic) contradiction of being both peer and a tutor. Trimbur voiced prevailing academic attitudes, referring to peer tutoring as “the blind leading the blind” (22). Emphasizing the authoritative nature of the word “tutor,” he states that peers “are not qualified to tutor, to pass down knowledge to their tutees” (22). Later, Runciman argued that “we ought to recognize that the words ‘tutor,’ ‘tutoring,’ and ‘tutee’ do not accurately portray the full range of writing center activities. These words limit both our clientele and our budgets; they make our activities appear both marginal and exclusively remedial” (33). Critiquing the term “peer tutor,” Carino stated that examining each term independently “uncovers the issues of power and authority beneath them, issues imbricated in the institutional position of the writing center but carrying over into the pedagogy of peer tutoring” (116). According to this argument, adding an adjective to an inaccurate term is likely ineffective in re-shaping connotations. The result can seem oxymoronic, like referring to someone as a “novice expert” or an “ignorant teacher.” The inherent contradiction could call the tutor’s role into question rather than adding clarity.

When it comes to names for writing centers, changes over time reflect their evolving emphasis as well as a desire to escape perceptions of marginality. “Lab” was the first term used by writing centers to define the space of the center (Boquet 466; Lerner 2). As early as the 1920s, labs focused on remediation, aiming to purify language (perhaps like a chemist might purify a chemical solution). It was not until the 1940s that writing center staff began to assume the role of nondirective counselors (Boquet 469). Although the role of writing centers has shifted, “lab” has continued to be regularly used by modern writing centers and writing center scholars, as evidenced by the publication of Purdue University’s Online Writing Lab and other similar sites (Inman and Sewell). Changes in writing center pedagogy, however, led to calls for replacing “lab” in order to distance modern writing centers from their original incarnations. Carino claimed that the word “lab” led to instructors treating writing centers as “a marginal place where the marginal student attends to the teacher’s marginal symbols on grammar errors” (35). A sense of the marginality of writing labs may have resulted from the interpretation of “lab” as an annex to the classroom where research would be carried out. In 1996 Grimm voiced similar concerns, claiming writing labs existed to “correct, measure, and supervise abnormal writers to help them meet the standards set by the institution” (533), as did Trimbur (in 2000), who referenced the long debate over the use of “lab” and the common worry that the word lent “pathologizing overtones” to the centers it represented. No less pathologizing, “writing clinic” gained popularity shortly after the use of “lab” (Boquet) and was also associated with remedial tutoring. Lerner describes the short life of the Dartmouth Writing Clinic and how it was perceived as a place where deficient writers could receive strictly remedial help (Lerner 15). It may be that the trend toward using “center” was aspirational, referencing the centrality of tutoring in the face of such marginalization.

Title Talk in the IWCA Listserv

For some professionals, what to call their tutors or whether to change terminology remains a persistent question. Occasional conversations over names and terms persist over the International Writing Center Association (IWCA) email list where directors occasionally ask for advice on a range of topics. Several conversation threads over the last decade or so reveal that professionals hold strong and divergent opinions. Those title discussions sometimes involve graduate students or leadership roles (“A New Title for our Graduate Coordinator?”). In one thread, several writing center professionals weighed in on alternatives to the title “ESL Specialist” position, for example (“Job Title Suggestions”). Opinions have also been shared at length about the general term for undergraduate tutors (“Tutor Vs. Consultant”). Janet Zepernick of Pittsburg State University articulated one of the commonplace arguments made in the field for abandoning traditional terminology: “You go to a tutor when you feel yourself to be weak in the subject, but you call in a consultant when the work is important…I think the shift in terminology is an important part of the new identity we’re crafting on campus” (“Tutor Vs. Consultant”). Katherine Kirkpatrick from Clarkson College disagreed, admitting, “I always thought consultant sounded so black ops/hired cleaner of situations” (“Tutor Vs. Consultant”). Later, Zepernick would insist that using “consultant” radically shaped the student/tutor relationship, that the title “tutor” encouraged students to give over control of their work while “consultant” encouraged them to have more agency as seekers of expert support, making coming to the writing center “an expression of agency and self-efficacy on the part of the client” (“Tutor or Consultant?”). The consultant/client relationship here seems to have clear business valence. Lisa Morzano commented that her center had recently switched to using the word “coach,” using a sports metaphor to explain their sense of the term: “It seems to communicate that the student is clearly the one ‘in’ the game while we’re on the sidelines” (“Tutor Vs. Consultant”). Donna Evans from Eastern Oregon University said that her writing center was changing back to “tutor” to be consistent with the other learning centers on her campus. She also mentioned that her center was currently changing from the name “Writing Lab” to “Writing Center” (“Tutor Vs. Consultant”). Later Starkweather voiced concern that the connotation of “consultant” might make the tutors seem expendable in a budget crunch at a for-profit institution (“Tutor or Consultant?”) These threads show that directors and writing center professionals continue to hold a range of views about different titles and that those titles can be put in place as a way of framing identities and leaning on analogies, but they can also simply be adopted for internal reasons or concerns at a given institution.

Some consistency can be seen in efforts to democratize titles, giving tutors a choice in the matter. Muriel Harris stressed in one thread that “it’s also a matter of what term the tutors want. If we truly theorize about and practice collaboration, then we too collaborate with our tutors” (“Tutor Vs. Consultant”). When given the opportunity to choose their own title, her tutors picked “Undergraduate Teaching Assistant,” because they believed it would bolster their resumes. Similarly, Deanna Mascle of Morehead State University wrote, “When we were inventing our Writing Studio I gave them their own choice and they designated themselves as peer writers” (“Tutor or Consultant?” 2012). Continued conversations on this decades-long debate suggests that none of the strong arguments in writing center scholarship have been completely successful in shifting to new terminology.

Tutor Persists in Scholarship

Despite calls for replacing “tutor,” the term is still in regular use in writing center scholarly discourse. When we first started to investigate this topic in the center I directed, we accessed every article published by Writing Center Journal in the preceding ten years (2006-2016). Of the 1,096 key words from 116 peer reviewed articles, there were 114 uses of the word “tutor” and only 13 uses of the word “consultant.” In article titles specifically, there were 35 uses of “tutor” and just 2 uses of “consultant.” The most recent issue of Writing Center Journal used “tutor” or “tutoring” 15 times across its titles and abstracts with no other variants. Etymologically, the word “coach” was actually used to refer to extra academic tutoring long before its more common sports context, and it sees some use today as a term for tutors [3]. While not seen as often as tutor in published scholarship, “Consultant” has gained ground [4]. For example, those developing the survey for the National Census of Writing used “consultant” exclusively in their questionnaire despite occasionally mixing terminology, as in the question “Are your writing center consultants professional tutors?” In scholarship, however, it seems “tutor” remains the standard title and term for writing center work [5].

The remainder of this study aims to track the actual impact of calls to change terminology by looking at the public face of writing centers in the United States. To what extent do writing center practitioners seem to have responded to critiques from scholars about the traditional names for center and tutors by adopting less traditional ones? In terms of quantitative representation of actual practice, the field remains relatively uncharted [6]. Despite the long history of discontent with the use of certain words to describe writing center activity, no study to date has investigated the actual use of these words in writing center names and job titles, or the popularity of their alternatives. When it comes to finding information about current practice in writing programs and writing centers, surveys have been popular. This study is an effort to reduce subjective bias in this discourse and to engage in methodologies that can work as an alternative or supplement to the preponderance of self-reported survey data in the field. This study also represents an initial effort to map writing centers in the United States, providing data and grounding for further study by collecting and analyzing publicly-accessible data from university websites.

Method of Current Study

In order to examine present writing center tutor job titles, staffing, and center names, this study examines these terms as represented in official university websites available to the public. The present study sought to determine tutor titles and center names based on public self-representation through web pages within a substantial subset of all writing centers in the United States. The websites of 575 higher education institutions were investigated. The institutions were selected through the use of the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS; National Center for Education Statistics). The selection criteria consisted of institutions offering 4-year baccalaureate degrees and above, private and public not-for-profit, and a reported enrollment of at least 5,000 students. This search produced a set of 575 university names and 12-month unduplicated headcount enrollments of graduate and undergraduate students. The data was compiled into a spreadsheet.

In order to speed up the process and to gather more data, redundant groups of universities were given to undergraduate and graduate student researchers supplemented by searches and cross-checking from writing center staff. The investigators were instructed to perform a Google internet search to find each university’s official writing center website. Web links were recorded on the spreadsheet for later reference. Investigators read each university web page or pages to determine the answers to the following questions:

Does this university have a writing center? If so, what is its official name?

Does this university writing center employ undergraduate students as tutors? If so, what job title is used to describe them?

Does this university writing center employ graduate students as tutors? If so, what job title is used to describe them?

Does this university writing center employ professional tutors? If so, what job title is used to describe them?

If on these web pages, more than one title was used to describe tutors for a single undergraduate, graduate, or professional position, investigators were instructed to record both titles. When listing the name of the center, if writing centers or writing tutoring were housed in a learning commons and not in an independent center, investigators were instructed to list the name of that center. If no writing center webpage could be located or no reference was found to a writing center or writing tutors in a thorough search of the university website, investigators were instructed to record no writing center name and assume there was no center for tutoring writing at that university. If no evidence for an undergraduate, graduate, or professional position could be found, the investigators were instructed to record “unknown” for the category.

Results

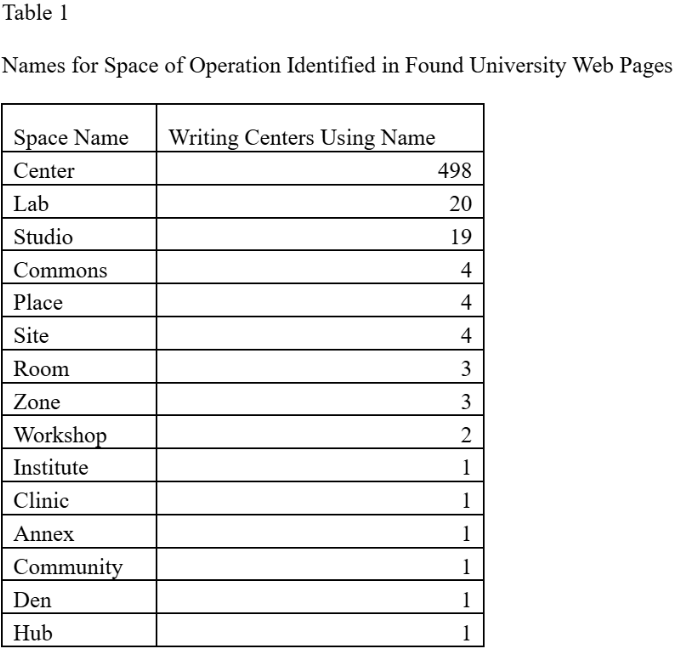

Of the 575 institutions investigated, 567 were confirmed to have writing centers or a tutoring program with some description on official university websites. 498 of the identified writing center names used “center” to describe their space of operation. In total, 15 different names for space were identified within the found writing center names. “Center” was the clear consensus representing nearly 89% of all names for spaces of operation identified in the study. Table 1 shows the frequency of the different names for writing (or university tutoring) centers.

94 unique combinations of job titles for writing center tutors were found. In these titles, 18 different terms for tutor were identified. Undergraduate, graduate, and professional job titles were counted separately and combined to arrive at the final totals. Table 2 shows all different terms for “tutor” identified and how many times each term was used, regardless of tutor type. In an analysis of all job titles combined (not divided by tutor type), “tutor” was found to appear the most frequently, followed by “consultant.” Note that “peer” was only used as an adjective modifying another tutor term in several combinations like “Peer Tutor” (occurring most at 65 times), “Peer Consultant,” and “Peer Writing Specialist.” While “consultant” had a significant showing with 324 uses, it still lags behind “tutor.” When modifying terms like “peer” are excluded to focus on primary job titles, “tutor” emerges as the majority term, accounting for approximately 54% of all titles identified and more if term mixing were not present (instances using both “consultant” and “tutor” on the website). “Professional” was counted as a modified 28 times. The term “consultant” was also often combined with “tutor,” either in describing what consultants do or in mixed titles across pages. 37 instances of universities using both “tutor” and “coach” were recorded and were counted equally for both below.

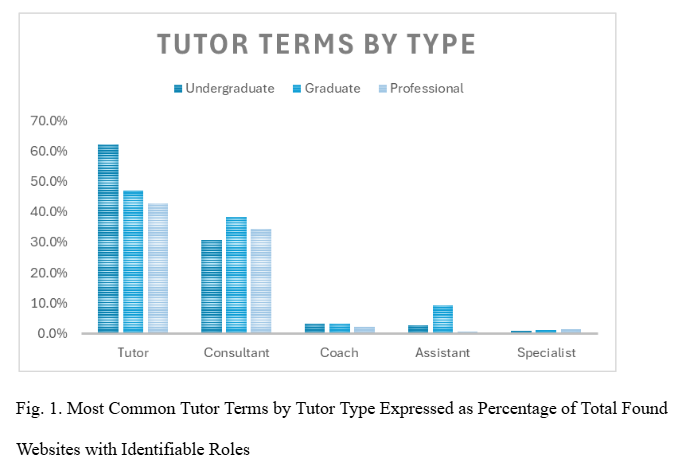

Out of the 567 found institutional websites, 504 indicated that they employed undergraduate students as tutors, 291 indicated that they employed graduate students as tutors, and 128 indicated that they employed professional tutors. Figure 1 shows the distribution of the most common terms used for tutor roles, separated by tutor type and expressed as a percentage of the found websites where roles were successfully identified. “Tutor” was most used in every tutor type, followed by “consultant.” The third most common terms were “coach” and “assistant.” As mentioned, the word “professional” was frequently attached to those in a professional role. “Assistant” was most frequently attached to graduate student positions, but was also employed as a role at the undergraduate level in lieu of “tutor,” as in “Writing Assistant.”

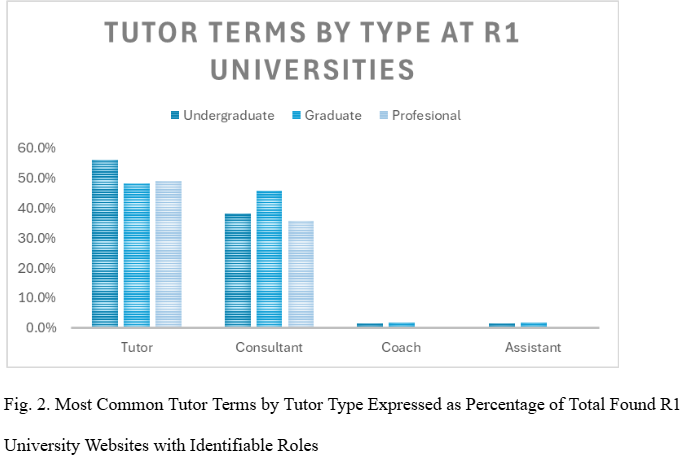

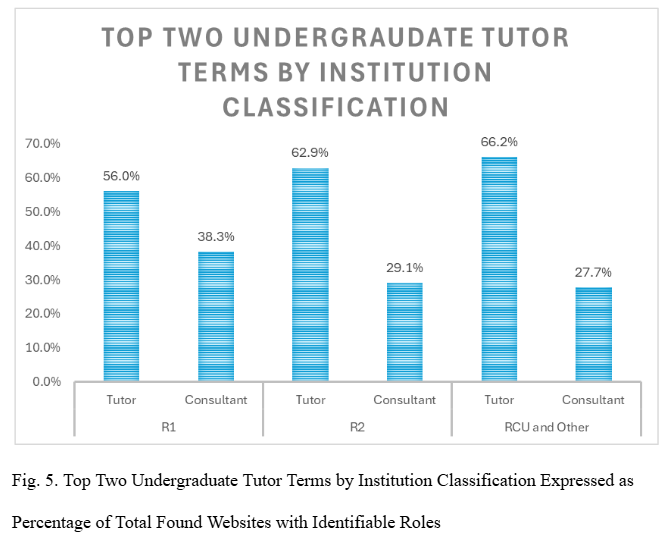

The average total enrollment for institutions that used “consultant” was 19% higher than the average total enrollment for institutions that used “tutor” (17,648 enrollment average for “consultant,” 14,602 for “tutor”). Seven out of 10 of the largest universities used “consultant” (or “consultant/tutor”), with “tutor” only in two instances, and a single instance of “coach.” When grouped into Carnegie research classifications of R1, R2, and RCU/Other, the percentage of universities using “consultant” varied significantly across classification, with “consultant” achieving its highest use most frequently at R1 Universities. The percentages in Figures 2 through 5 are calculated as a percentage of use based on the number of institutions with websites that were located and contained information about tutor titles. Because “consultant” and “tutor” were counted twice for some institutions that used both terms in their website, the total may not add up to 100 percent. Looking at Figure 2 through Figure 5 shows that “tutor” was the most popular term across all institution types and for all tutor types except for the RCU and Other category where professional tutors were more likely to have “consultant” as a title. Despite “tutor”’s dominance, “consultant” has a significantly higher appearance at R1 institutions at 38.3% in comparison to 29.1% and 27.7% at R1 and RCU/Other universities respectively. Figure 5 illustrates this difference and also shows the prevalence of “tutor” in the RCU/Other category observed in 66.2% of writing centers for which titles were found.

227 identified writing center websites indicated their writing center exclusively employed undergraduate tutors. This was the most common staffing arrangement. 175 writing center websites indicated their center employed only undergraduates and graduates; 74 indicated they employed all tutor types; 27 indicated they employed only undergraduates and professionals; 21 indicated they employed only graduate students; 19 indicated they employed graduates and professionals; 6 indicated they only employed professional tutors. When writing centers employed only undergraduate and professional tutors, job titles were commonly adjusted for tutor type (21 out of the 27 writing centers used different titles for different tutor types (72%). Job title adjustments were less common for other staffing arrangements. For centers employing undergraduates and graduates, job titles were adjusted in 27 of the total 175 centers (16%). Only one center that exclusively employed graduate and professional tutors adjusted job titles for different tutor types. In a regional analysis of the top three most used tutor terms, uses of “coach” were most concentrated in the East and Midwest. No regional trends were observed for “tutor” or “consultant.” See distribution maps in appendix.

Discussion

The data reflects a clear shift in names for space in the writing center community, matching common historical narratives and corroborating the historical narrative. “Lab,” once considered a name in wide use, now has been largely replaced by “center” though some 20 instances of “lab” were recorded in our data. This suggests that previous arguments to avoid “lab” have been successful in advocating a term that does not carry connotations of formulaic science and experimentation that may result in failure. Other less popular names carried implications that helped convey the writing center’s purpose. “Hub,” for example, implies a place where connections between writers can take place, and “studio” implies artistry and creative expression. However, although “center” was by far the most popular name in use, it is also a name that is less ripe with connotation. A center is simply a space, a focal point. Perhaps “center” has become so popular because it allows us to name a space for writing skill development support without having to decide exactly what role it will play in the writer’s experience. It also may match institutional terms for learning centers in other disciplines. Adopting a writing center name that offers few preconceptions may fail to immediately attract writers to writing center services (a product is more difficult to sell if its name does not reflect its function), but “center” may allow writers to approach writing centers on the right foot, with an open mind.

The analysis of tutor job titles and tutor terms, however, tells a different story. “Tutor” remains the most popular tutor term in use, across all tutor types, despite the many writing center articles taking issue with it. There was also extensive diversity in the minority that elected to use an alternative term. Although “tutor” was by far the most common single term, it led by a narrower margin compared to the overwhelming show for “center.” Potentially, this could signal a shift in the writing center community. Perhaps so many alternatives to “tutor” are in use because writing centers have begun to search for a more agreeable term but have yet to settle on the definitive solution. However, as expressed in the conversations on the IWCA listserv, it may be more likely that writing centers’ self-representations are constrained by the greater university ecosystem. “Tutor” may still be the most used term in our field not out of choice, but because of a need to validate the center’s work to departments, instructors, or those who control funding.

This explanation could account for the 28 cases identified of writing centers using “tutor” and “consultant” interchangeably to describe their staff. Some of these writing center websites, such as the website of Loyola University Maryland's Writing Center, at the time of collection, used "tutor" to describe their tutors but used "consultations" to describe sessions with tutors. Others, like the Writing Center of Minnesota State University-Mankato, would use "consultant" on their website, but use "tutor" in the website's navigation menu. Other centers used different terminology on different web pages. California State University-San Marcos' Writing Center described employing "certified student consultants" on their mission statement web page, but advertised "tutoring" on a page describing their services. Centers seem to be caught between advertising to two different groups: those outside the center and those within. Using terms that outside parties may recognize is advantageous, but these terms may also misrepresent how employees think about their work. As a result, two contradicting images of writing center activity are offered in the hopes of attracting more users, leaving readers to interpret which part of the advertisement is accurate. However, it is possible that consciously using multiple terms and the use of conflicting terms is evidence that that names are dynamic and rhetorical, that perhaps a single term feels insufficient to describe the varied activities involved in tutoring writing.

Size and type of institution also seem to play a significant role in naming conventions. “Consultant” had a tendency to be used by institutions with larger total enrollments. It could be that schools with larger writing center programs have responded to arguments in scholarship critiquing prevailing tutor terminology. Another reason, however, may be the nature of the work conducted, which makes sense in the clear trend toward “consultant” at R1 universities and for graduate and professional staff at other institutions. It seems likely that those institutions with a more prevalent research mission as well as those in professional and graduate positions may work more often with those who are gaining or have gained advanced expertise in particular fields. A plausible explanation would be that “consultant” avoids the kind of promise of subject expertise and the remedial association individuals might have with “tutor” when dealing with more advanced writers.

Still no solid conclusions can be reached as to why certain names are employed based on this study alone, and the study still found several different terms in use. Unlike the neutral name center, all identified tutor terms carried clear connotations that define the interaction between tutor and writer. Popular wisdom as discussed in the beginning section of the paper has it that the title of “tutor” implies that the tutor is more knowledgeable than the writer, setting up an expectation that parts of the draft may be deemed correct or incorrect. “Consultant” may absolve tutors of having to stand by the effectiveness of their feedback, but it could still be seen as offering a strong signal of expertise. “Coach” connotes a motivating force that can whip students into shape in order to face the challenges (though probably not hollering such things as “excuses are crutches for losers” like my Junior High basketball coach did). Depending on one’s experience, “coach” could invoke a friendly observer from the sidelines, offering timely suggestions. A “mentor” implies a tutor writers can look up to and model themselves after. “Responder” is decidedly more neutral, focusing on a central activity tutors engage in. It might suggest a tutor who offers honest feedback, perhaps without attention to skill development. Writers might think a “collaborator,” “writer,” or “assistant” is a tutor who will help compose a document, which could be problematic, depending on how students and instructors understand the function of such collaboration. Any of the 18 base tutor terms identified carry implications and connotations that could point to some aspects of what it means to be a writing center tutor while ignoring others.

Room for Play?

Regarding staff, most institutions exclusively employ undergraduate students as tutors, followed closely by employing undergraduate and graduate students together. This suggests that perhaps the word “tutor,” which establishes a tutor/student hierarchy (an arrangement perhaps more fitting for a professional tutor meeting with an undergraduate student), is not an entirely accurate depiction of common writing center staff. “Peer” continues to be used to modify tutor to reduce hierarchical impressions. Job titles for writing center tutors were most likely to change per tutor type if the writing center employed only undergraduate student tutors and professional tutors. This trend is likely the result of recognizing the difference in expertise and authority between degree-holding professional tutors and undergraduate student tutors. Despite debate, however, few would argue with the fact that tutors do typically have some knowledge and training that most student writers do not. The issue may be less the hierarchical terminology and more the fact that the term does not describe all the collaborative roles performed in a writing center: acting as a sounding board, being a motivator, and many other elements of writing center sessions. Though writing centers are usually free services, they nevertheless rely on marketing of some kind to draw students in. They project a brand image designed to attract writers in a certain university community. The field of marketing has long held that images and words can influence user attraction and experience. Keller, Heckler, and Houston, for example, claim that selecting the proper name can “enhance brand awareness and/or help create a favorable brand image for a newly introduced product,” and that the most effective names are “inherently meaningful…so that the name itself conveys relevant product information” (48). Effective names can reinforce what the product is (like Simply Orange as orange juice) or can suggest certain attributes (Carnival Cruise Lines as a place to have a good time) (48). From this perspective, writing center titles for personnel and location names may not be “inherently meaningful.” “Tutor,” as has been suggested, may imply remediation and hierarchy; in addition, it does not necessarily define what a writing center tutor is.

One thing is clear from this study, if the field wishes to abandon the term “tutor,” much change would still need to occur. In practice, although at a relatively small number of institutions, enough variety exists to indicate space even for neologism. “Labbie,” a term used by The University of West Florida’s Writing Lab, is a neologism for “laboratory assistant” (Kemmer), which likely draws parallels between experimentation and discovery and the writing process. Although the link between writing centers and laboratories might be undesirable, the idea of wordsmithing a tutor term to describe writing center activity might have some appeal, especially for those who are enamored with neither the business-like “consultant” nor the “coach” with its sports metaphors. But, aside from running into the difficulty of needing to convey the meaning of some neologism to end users, those attempting this may run into additional problems. Even made up words could evoke connotative echoes of other terms.

The difficulty in selecting or creating any term is that it simultaneously must sound approachable and useful, while also preserving a degree of professionalism for the tutors who have to put it on their resumes. This, mixed with a combination of other factors such as campus culture and administrative structure, makes finding a perfect word for everyone impossible. Isaacs and Knight using publicly accessible information from 101 writing centers found that centers “range significantly in their scope of activities, mission, location, staffing, and public website presentation” (37). It is unlikely that a single inherently meaningful word can be found that would capture such diversity.

In my center, our erstwhile search for alternatives to the use of “coach” (yes, I am the one with the sports metaphor aversion) turned up amusing substitutes that sound interesting, but ultimately miss the mark. Among our rejected ideas were “agent,” “detective,” “emissary,” “ambassador,” “model,” and “maven.” We picked each of these terms apart, carefully studying their etymologies, but eventually abandoned them. But I have to admit that “Labbie” puts a smile on my face, and I was pleasantly surprised by the variety of terms still in use which suggests there may be room yet for play in our naming culture. Future studies may find ways to prove or discredit the effects of staff titles empirically. Imagine, for a moment, a center that uses an archaic pedagogical term like “Lore-master,” a word from the 1400s for a master in learning (Oxford English Dictionary). A lore-master’s acolytes were known as “lore-children” (Oxford English Dictionary). What would a writing center that employs “lore-masters” look like? What relationship would they have with their lore children? The medieval fantasy invoked by such a term, especially given its revival in the terminology of games like World of Warcraft could be playful (Blizzard Entertainment). I would much rather have a visit with a lore-child than a tutee and probably even a client. Taken seriously, however, the paternalistic imbalance of power and authority could make both tutors and writers uncomfortable. Such terminology might emphasize some of the negative aspects of hierarchy or practice, as would be the case if a writing clinic were named “The Writing E. R.” in an institutional community that approached the center as a place to take writing catastrophes for last-minute life support measures, a practice that would defy concepts of revision and collaboration in learning. These extreme names punch up some of the issues writing centers deal with, whatever they may be called. Still, because a writing center’s core philosophies should influence how it represents itself to others, tutor terms and center names are arguably important as they are the two most salient uses of language used in association with center activity.

Limitations

The current study’s focus on publicly accessible university websites created some limitations on what information could be gathered. Some webpages require university logins to access content and scheduling systems. Other websites were considerably less developed, offering limited information on a single webpage. Because of the variety of information offered on the public websites, some data could not be consistently collected. I initially wanted to investigate how many centers employed tenured faculty as directors, for example, but this question was dropped from our initial study design because we found that many sites did not indicate who the director was or whether or not they were also faculty at the university. More extensive searching could determine if terminology and center self-representation correlates with differences in staff and leadership, as well as help verify the validity of the current findings. The list was first started as a thought experiment when I was directing the Multiliteracies Center at Michigan Tech and was expanded for the collaborative research effort, so some universities had merged or changed names. I have tried to account for these changes but kept data where relevant. R1 classification is based on the Carnegie Classification as of 2025, not necessarily the classification when the data was first collected. In addition, the collaborative nature of the research means that, although I did verify many of the websites personally, I relied on data obtained from researchers that I verified when something was in obvious error. In that regard, there is room for human error that went unnoticed. Websites also change over time, and some URLs were broken at time of writing, sometimes because a website location changes or because a center’s website disappears completely or is replaced by a new version. Future research could seek additional and current data and could also include using Generative AI tools to collect data [7].

Conclusion

The findings of this study indicate that tutors still exist in great numbers. Since many centers still employ the word, it arguably remains useful for employees in writing centers, but whatever term a center uses, that term may need to be defined for audiences that bring a set of assumptions to what tutoring is. While “tutor” still has the stage and “consultant” may be anxiously waiting in the wings, it may be possible for centers to find other terms for their employees. Taking inspiration from the use of “center” over “lab,” perhaps one solution would be to move toward a more neutral tutor term that users will recognize. That move could be pragmatic, if bland [8]. Writing centers may benefit from finding more powerful and succinct ways to define themselves in a complex academic landscape of multiple literacies and modes, and names and terms may be a small, imperfect component of that endeavor. Further studies could track these trends over time. Empirical studies could test the efficacy of the terms that have been so vigorously proposed and defended. Such studies could allow us to move beyond conjecture and anecdotal evidence about the efficacy of our terminology.

Some previous scholarship addressing the naming of tutors has attempted to have the final word on the conversation, to implement new names or finally solve the problem of what we call those who work in centers. The data suggests that this conversation remains open, a conversation that must be responded to by a diversity of institutions nationally. Writing centers permeate the landscape of higher education in the United States, and the variety of leadership for those centers and the nature of writing center scholarship means that in each context questions of names and titles may continue, as my review of the IWCA listserv attests. One important takeaway from this study is that there is no full consensus on a national level of what centers or tutors should be called, making this far from an esoteric debate from the 1990s. In identifying themselves, directors and tutors walk a balance between desirable self-representations on the one handand identifiability and accuracy on the other. Titles may not be the only way to describe our services. The question then turns away from “What should tutors be called?” to “What does being a tutor mean to you where you are?” In this view, what matters is the way we define and talk about our work. Messaging and terminology often occur on a local level, but the online presence of a center also paints a picture of its values and offerings. On a national level, tutoring as a practice has widely been accepted as necessary, but with continued upheaval in generative AI technology related to writing, the face and perhaps the name writing centers present for themselves continue to be important tools in shaping perceptions and reality.

Notes

1. For the remainder of this article, I will use the terms “tutor” and “writing center” for convenience and because those remain the most widely-used terms in writing center studies.

2. Sands suggests that any name should be measured by four principles—accuracy, aspiration, complexity, and coherence—to ensure that the chosen tropes effectively and fully represent the reality of writing center work (11).

3. The word “coach” has a longer history in academia than might be expected. Its original meaning referred to carriages as a means of conveyance. This meaning was adopted as a metaphor in 1830 as a slang term at Oxford University to describe unofficial tutors who helped students through university exams, presumably getting students to positive outcomes more quickly. These tutors operated independently of the official tutors at the institution. This slang led to its use as a verb, recorded in 1848 to mean to prepare someone for an exam (Oxford English Dictionary, 2016). This sense of getting someone from point A to point B more rapidly than they could on their own then was used generally. It was not until 1885 that coach came to be used in an athletic context. Interestingly, the word coach is most likely adopted in writing center parlance with the sports metaphor in mind, as is the case with my previous institution, where the title has been in use in most learning centers across campus. Although coach may free tutors up to be more casual observers/commentators “from the sidelines,” rather than content experts, coaches of the sports variety can also invoke negative connotations of harsh, motivating individuals who push athletes to their limits.

4. The term “consultant,” originally a word used to refer to those who consulted oracles. It was first used in 1894 to describe those qualified to provide professional advice (Oxford English Dictionary). Much more common in business contexts, the word has only been applied in an academic context relatively recently.

5. The word “tutor” is the traditional term used to describe a person who offers academic assistance outside of a classroom. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the earliest known use of the word in this context was in 1398, in reference to private tutors.

6. Efforts like the National Census on Writing are a step in the right direction, though relying on self-reported survey data has its limitations.

7. My own experimentation shows some promise here, though the context window for processing large amounts of data creates problems with fabrication. Such scraping as an iterative process, however, could be a way to replicate and compare to the data obtained in this study and others.

8. Some innovations, however, don’t take hold. The idea of a multiliteracy (or multiliteracies) center created some stir but has since faded. In my data, the only remaining center with multiliteracy in the title appears to be California State University, Channel Islands. I directed the Michigan Tech Multiliteracies Center, which had been thus named by Nancy Grimm. The subsequent director changed the name back to Writing Center aiming for easier recognizability on campus.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank two Assistant Directors who helped me in this work. Rebecca Frost was helpful in finding sources when I initially started thinking of the topic, and William De Herder was an immense help in organizing data collection and initial analysis. I'd especially like to thank William for putting up with a lot of talk about tutor titles. I also owe a thanks to the graduate students and undergraduate coaches who helped me collect the data for this study.

References

Balester, Valerie, et al. "The Idea of a Multiliteracy Center: Six Responses." Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, www.praxisuwc.com/baletser-et-al-92/.

Blizzard Entertainment. World of Warcraft. Blizzard Entertainment, 2004.

Boquet, Elizabeth H. "'Our Little Secret': A History of Writing Centers, Pre- to Post-Open Admissions." College Composition and Communication, vol. 50, no. 3, 1999, pp. 463-482. JSTOR, doi:10.2307/358861.

Carino, Peter. "Power and Authority in Peer Tutoring." The Center Will Hold: Critical Perspectives on Writing Center Scholarship, edited by Michael A. Pemberton and Joyce Kinkead, Utah State University Press, 2003, pp. 96-113.

---. "What We Talk About When We Talk About Our Metaphors: A Cultural Critique of Clinic, Lab, and Center." Writing Center Journal, vol. 13, no. 1, 1992, pp. 31-42.

Cheatle, Joseph, and Margaret Bullerjahn. “Undergraduate Student Perceptions and the Writing Center.” WLN: A Journal of Writing Center Scholarship, vol. 40, no. 1, 2015, pp. 19–26. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.37514/WLN-J.2015.40.1.04.

Fenko, Anna, et al. "What's in a Name? The Effects of Sound Symbolism and Package Shape on Consumer Responses to Food Products." Food Quality and Preference, vol. 51, 2016, pp. 100-108. ScienceDirect, doi:10.1016/j.foodqual.2016.02.021.

Grant, Adam M., et al. "Job Titles as Identity Badges: How Self-Reflective Titles Can Reduce Emotional Exhaustion." Academy of Management Journal, vol. 57, no. 4, 2014, pp. 1201-1225. JSTOR, doi:10.5465/amj.2012.0338.

Grimm, Nancy M. "Rearticulating the Work of the Writing Center." College Composition and Communication, vol. 47, no. 4, 1996, pp. 523-548. JSTOR, doi:10.2307/358600.

Harris, Muriel. "Talking in the Middle: Why Writers Need Writing Tutors." College English, vol. 57, no. 1, 1995, pp. 27-42

Inman, James A., and Donna N. Sewell, editors. Taking Flight with OWLs: Examining Electronic Writing Center Work. Routledge, 2000.

Isaacs, Emily, and Melinda Knight. "A Bird's Eye View of Writing Centers: Institutional Infrastructure, Scope and Programmatic Issues, Reported Practices." Writing Program Administration, vol. 37, no. 2, 2014, pp. 36-67.

"Job Title Suggestions." WCenter, 2016, lyris.ttu.edu/read/messages?id=24817505#24817505.

Keller, Kevin Lane, et al. "The Effects of Brand Name Suggestiveness on Advertising Recall." Journal of Marketing, vol. 62, no. 1, 1998, pp. 48-57. JSTOR, doi:10.2307/1251802.

Kemmer, Suzanne. "The Rice University Neologisms Database." 2008, neologisms.rice.edu/index.php?a=term&d=1&t=8053.

Lerner, Neal. The Idea of a Writing Laboratory. Southern Illinois University Press, 2009.

---. "Rejecting the Remedial Brand: The Rise and Fall of the Dartmouth Writing Clinic." College Composition and Communication, vol. 59, no. 1, 2007, pp. 13-35. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/20456979.

National Census of Writing. 2015, writingcensus.swarthmore.edu.

National Center for Education Statistics. "Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System." 2016, nces.ed.gov/ipeds/datacenter/.

"A New Title for Our Graduate Coordinator?" WCenter, 2012, lyris.ttu.edu/read/messages?id=24981494#24981494.

North, Stephen. "The Idea of a Writing Center." College English, vol. 46, no. 5, 1984, pp. 433-446.

Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford UP, 2016, www.oed.com.

Romney, Abraham, and Karla Kitalong. "A Broad Spectrum of Multiliteracies: Toward an Integrated Approach to Multimodality and Multilingualism in Writing Centers." Southern Discourse in the Center: A Journal of Multiliteracy and Innovation, vol. 20, no. 1, 2016, pp. 10-30.

Runciman, Lex. "Defining Ourselves: Do We Really Want to Use the Word 'Tutor'?" Writing Center Journal, vol. 11, no. 1, 1990, pp. 27-34.

Sands, Scott R., "The Tropes We Tutor by: Names and Labels as Tropes in Writing Center Work" (2018). Theses and Dissertations. 942. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd/942

Spence, Charles. "Managing Sensory Expectations Concerning Products and Brands: Capitalizing on the Potential of Sound and Shape Symbolism." Journal of Consumer Psychology, vol. 22, no. 1, 2012, pp. 37-54. ScienceDirect, doi:10.1016/j.jcps.2011.09.004.

Trimber, John. "Multiliteracies, Social Futures, and Writing Centers." The Writing Center Journal, vol. 20, no. 2, 2000, pp. 29-32.

Trimbur, John. "Peer Tutoring: A Contradiction in Terms." Writing Center Journal, vol. 7, no. 2, 1987, pp. 21-28.

"Tutor or Consultant?" WCenter, 2012, lyris.ttu.edu/read/messages?id=19283351#19283351.

"Tutor vs. Consultant." WCenter, 2016, lyris.ttu.edu/read/messages?id=18940138#18940138.

Appendices

Appendix A

Regional Mapping of Tutor

Appendix B

Regional Mapping of Consultant

Appendix C

Regional Mapping of Coach