Praxis: A Writing Center Journal • Vol. 22, No. 3 (2025)

“How I Speak Doesn't Really Matter; What I Speak About Does”: BIPOC Tutor Voices on Linguistic Justice in the Writing Center

Chloe Ray

Claremont McKenna College

chloe.ray@claremontmckenna.edu

Erin Goldin

University of California, Merced

egoldin@ucmerced.edu

Abstract

Scholars in the field of writing center studies have previously, and continue to, criticize writing centers for upholding unjust systems, arguing for more practical, equitable, and inclusive anti-racist pedagogies–namely through means of linguistic justice. Within this is a call for more attention to the practices of Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) tutors and to Minority Serving Institutions (MSIs). In this small, IRB-approved project, we interviewed three BIPOC tutors employed at an MSI and Hispanic Serving Institution (HSI), exploring how these tutors conceptualize linguistic justice and how they practice it within their work at their university writing center. By listening to the experiences of these three tutors, we gained insight into the nuanced and complex ways in which their lived experiences and histories influence how they conceptualize linguistic justice, both for themselves and in their work in the writing center. Our research revealed how the multiplicity, complexity, and nuance of identity—specifically self-identification and belonging, the use of multilingualism and code-switching, and the defining of one’s authentic voice—affect how a tutor understands and performs linguistic justice. We hope that sharing these tutors’ voices will highlight a need to recognize the intersections and multiplicity of language, discourse, and identity that shapes tutors’ experiences with linguistic justice work as well as acknowledge the labor they perform when engaging in that work in the writing center.

Introduction

While previous scholarship has made important strides in addressing social and racial justice in the writing center context (e.g., Diab et al.; Greenfield and Rowan; Grimm; Villanueva), linguistic justice, as both a term and form of strategic action, has received increasing focus. Many posit the 1974 CCCC’s conference statement, Students’ Right to Their Own Language, as an important catalyst for the pursuit of racial equity and justice within the field. More recently, the emphasis on anti-racist practices and linguistic justice can be seen from the 2022 CCCC’s conference theme “The Promises and Perils of Higher Education: Our Discipline’s Commitment to Diversity, Equity, and Linguistic Justice” (Perryman-Clark). Linguistic justice within writing center scholarship includes the 2023 edited collection Writing Centers and Racial Justice: A Guidebook for Critical Praxis (Morrison and Garriott) and The Peer Review’s 2024 special issue Enacting Linguistic Justice in/through Writing Centers (Tucker and Bouza).

We believe that writing centers, particularly writing centers that use a peer tutor model, are uniquely positioned not just to support students across diverse linguistic backgrounds, but to actively advocate for linguistic justice within the academy. At the same time, we agree with recent calls to include more tutor voices in our research on how writing centers effectively enact linguistic justice. As Faith Thompson writes in her piece on the practicality of anti-racist tutor training, “Writing centers seeking to actualize antiracist practices must start with tutors. They should move beyond the purely theoretical and reimagine writing center pedagogies.” The conversations about linguistic justice in writing center work are still largely missing the voices and experiences of Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) writing center tutors. Coupled with this is the need to assess the practices of tutors at minority-serving institutions (MSIs), as much of the scholarship is primarily informed and practiced by tutors at predominantly white institutions (PWIs) (Camarillo). Thus, our research explores how BIPOC writing center tutors conceptualize linguistic justice and implement it in their tutoring practices. Throughout this project, we have learned, and thus aim to argue, how contextualization and deeper awareness of our tutor’s complex identities are necessary for the practical implementation of anti-racist and justice-informed pedagogy in writing centers.

Defining the Practice of Linguistic Justice

Despite the term “linguistic justice” gaining traction across scholarship, its meaning, and what it specifically entails, fluctuates. The origin of the term linguistic justice is often tied to April Baker-Bell’s text of the same name. Baker-Bell, however, doesn’t explicitly define linguistic justice as a term; rather, she posits the focus of her text as “an antiracist approach to language and literacy education” that seeks to specifically dismantle “Anti-Black Linguistic Racism and white linguistic hegemony and supremacy in classrooms and in the world” (7). This definition has often been expanded as a means to dismantle the linguistic racism that affects a wider range of marginalized identities, languages, and discourses, as well as applied more specifically to college students, as opposed to the secondary students who were the focus of Baker-Bell’s study. Despite Baker-Bell’s context, pedagogy, and demographic age not being reflected in the specific context of most writing centers, her work is still referenced as a cornerstone of how to enact linguistic justice work in the field and in our centers (e.g., Thompson).

A direct definition of linguistic justice within the writing center context can be found in Lucia Pawlowski’s 2024 article, in which she demonstrates how writing center administrators can utilize our spaces as informational hubs and catalysts for institutional linguistic justice. She creates a “scaffolded approach” of introducing antiracism to “all writing center stakeholders” within one’s institution. Most notably, she defines three distinct levels of linguistic justice: linguistic diversity, linguistic equity, and linguistic justice. Pawlowski defines linguistic justice as the “most progressive and radical” level as it “calls for action: it is a solution-based vision” (emphasis in original). Pawlowski’s text is important because it is one of the few that offers a distinguishable definition of what it means to enact linguistic justice specifically within a writing center context. For example, instead of relying on Baker-Bell’s text to define linguistic justice, Pawlowski contextualizes it as an actionable form of linguistic justice because it is a pedagogical framework that offers concrete methods for dismantling anti-racism and linguistic prejudice within classroom curriculums.

While the discussions of anti-racist pedagogy within writing centers have informed the field for years (e.g., Greenfield and Rowan), the practical implementation of linguistic justice is still fairly new. Using Pawlowski’s definitions, we see linguistic justice—progressive and radical visions and action—in recent work that addresses how to specifically incorporate linguistically inclusive instruction into writing center sessions. Suggestions for linguistically inclusive practices are often strategy-based. For example, Zoe Esterly et al. discuss how the writing center is “strategically positioned” as a place for students to negotiate between their own linguistic practices and Standard Academic English (SAE), especially regarding grammar instruction (45). Other texts have worked to posit and promote linguistic “agency” and “resistance” in writing centers through the incorporation of translingual praxis (see Shapiro and Watson), or by turning to racial and critical literacies practices (see Johnson).

Within the conversation of linguistic justice, how it is being enacted is still rather varied and hard to define concretely. For example, code-meshing, a rhetorical technique that involves the mixing of SAE and the author’s non-academic discourse, as opposed to code-switching, which is the practice of altering between discourses, may be regarded as an actionable strategy to be employed by a tutor in a session as a means to promote linguistic justice. However, we struggled to locate many examples within scholarship that present tutor perspectives on the ease or effectiveness of this or other particular strategies that are designed specifically to encourage linguistic justice. Overall, we noticed that the literature leans more theoretical and suggestive, with the voices and perspectives of administrators primarily being centered. Needless to say, linguistic justice is not merely a special topic or theme, but a movement that must be continuously implemented, revised, and ongoing. Thus, we see a need for more examples that represent how linguistic justice is enacted by tutors across various writing center contexts.

Defining Multiplicity

Although not always explicitly stated, conversations that are often inherent to linguistic justice are those concerning the multiplicity of one’s identity. One of the core goals of linguistic justice work is, as Baker-Bell states, to dismantle from classrooms the linguistic hegemony that places SAE, a language form that reflects dominant white linguistic codes, as one equivalent to power and correctness. On an individual level, linguistic justice is about valuing the experience, culture, history, and epistemology that is intrinsically tied to one’s language use, both rhetorically and ideologically. Language is identity, identity being something that is always a plurality. Thus, linguistic justice must be about acknowledging the plurality of linguistic identity—the ones we are taught at home, at school, and in our various communities. This is how we’ve come to understand multiplicity in relation to linguistic justice and identity development, a core focus of our study.

Positionality and Stance

We acknowledge that, as individuals, scholars, and writing center practitioners, we occupy various, intersecting identities which shape how we understand and engage with the world, including how we approach our research. A central goal of our research was to create space for the voices of our undergraduate tutors, who have their own unique positionalities, identities, and experiences. However, we knew from the very beginning of this project that even taking on the role of “researcher” to interview and write about these tutors’ experiences was setting up a dynamic that is already limiting to that goal. We knew we would be filtering those voices through our own—and that this was not something we could do without being attentive to the interplay of our own positionalities with those of the tutors we interviewed and with the overall research and writing process.

It is necessary to start by identifying our positionalities. Chloe is a multiracial (African-American/white), able-bodied, cis-gendered woman. She was a first-generation college student who began working in a writing center as an undergraduate. She is currently in a non-faculty position as the Assistant Director of a writing center at a private, liberal arts college (PWI). Erin is a white, able-bodied, cis-gendered woman from a background of relative privilege. She has worked in writing centers, starting as an undergraduate, for over 20 years. She is currently in a non-faculty academic position as Director of a writing center at an institution designated Hispanic-Serving Institution (HSI), Asian American, and Native American Pacific Islander-Serving Institution (AANAPISI), and MSI. While we were not working together at the same institution at the time we conducted this research, our initial conversations about linguistic justice and the need for research about the experiences of BIPOC tutors emerged at a time when we were institutional colleagues.

It is, however, not enough to disclose our positionalities; we also knew we needed to be self-reflexive throughout the research and writing process. Elizabeth Chiseri-Strater explains that in order to “achieve a reflexive stance, the researcher needs to bend back upon herself as well as the other as an object of study” (119). By turning back on ourselves, we are able to attend to our role in the research process as well as our relationships with the tutors, with each other, and with the broader writing center community we wanted to share these voices with. While we don’t write about ourselves explicitly, we were present throughout the research process—and we made decisions about what we were writing and how we were writing it.

Because we wanted to focus on the voices and experiences of these undergraduate BIPOC tutors, we opted to engage in semi-structured, in-depth interviews. Irvin Seidman explains that “at the root of in-depth interviewing is an interest in understanding the experience of other people and the meaning they make of that experience” (9). However, unless tutors co-authored their stories, something we couldn’t do properly in the scope and timing of this project, this piece cannot be a pure representation of their voices and experiences. We are writing as researchers, thus, we are making meaning alongside their stories. As we wanted to present these tutors as authentically as possible, we emphasized long excerpts with minimal editing or paraphrasing in the “Results” section and aimed to relegate as much of our “interpretation” as possible to later sections.

Methods

Research Site & Relationships

University of California, Merced is a public land-grant university located in the San Joaquin Valley (aka the Central Valley) of California. With a student population that is 91% BIPOC (CIE), UC Merced is a HSI, AANAPISI, and MSI. As of Fall 2023, UC Merced’s undergraduate population was 65% first-generation and 59% Pell eligible. Sixty-six percent of all undergraduates are multilingual, meaning they speak a language other than English or they speak English and another language (CIE).

UC Merced’s University Writing Center (UWC) began as a pilot program in 2014 and was established as a full program in 2017. The UWC employs approximately 18 undergraduate students from a variety of disciplines and one graduate student. The students employed by the UWC generally represent the student population in that they are predominantly BIPOC, first-generation, and multilingual.

It is important to note that both Erin and Chloe have existing relationships with the UWC tutors through a variety of roles: Erin’s role as director, Chloe’s role as instructor of writing, including an upper-division tutor pedagogy course that collaborated closely with the UWC, and both serving as mentors to students who were often in Chloe’s classes as well as working with Erin in the UWC. Because of Erin’s director role and the power inherent to that position in relation to the tutors, she was not involved in any of the recruitment or interview processes. At the time this research was conducted, Chloe was no longer working at UC Merced, but multiple former students of hers were still working in the UWC. Because of this existing relationship, these tutors were able to open up to Chloe during the interviews in a way they may not have felt comfortable sharing with a stranger.

Data Collection & Analysis

Tutors were invited to participate in these interviews during a staff meeting that Chloe attended via Zoom. At that meeting, she presented a summary of the research project, including sharing the research question and goal of publication, and invited tutors who identify as BIPOC to participate if they had time and interest. Three undergraduate BIPOC tutors volunteered to participate and were able to schedule interviews with Chloe. Interviews were conducted via Zoom and averaged 50 minutes in length.

In these interviews, Chloe asked questions about tutors’ language and identity (e.g., “How would you describe the relationship between language and your academic identity?”), questions about linguistic justice (e.g., “In what context have you heard linguistic justice being discussed?”), and their practices as writing center tutors (e.g., “Are there any elements of linguistic justice that you apply to your own practice within sessions as a writing center consultant?”). Follow-up questions were occasionally asked to allow tutors to expand on some of their thoughts, but the conversation always remained focused on identity, linguistic justice, and tutoring.

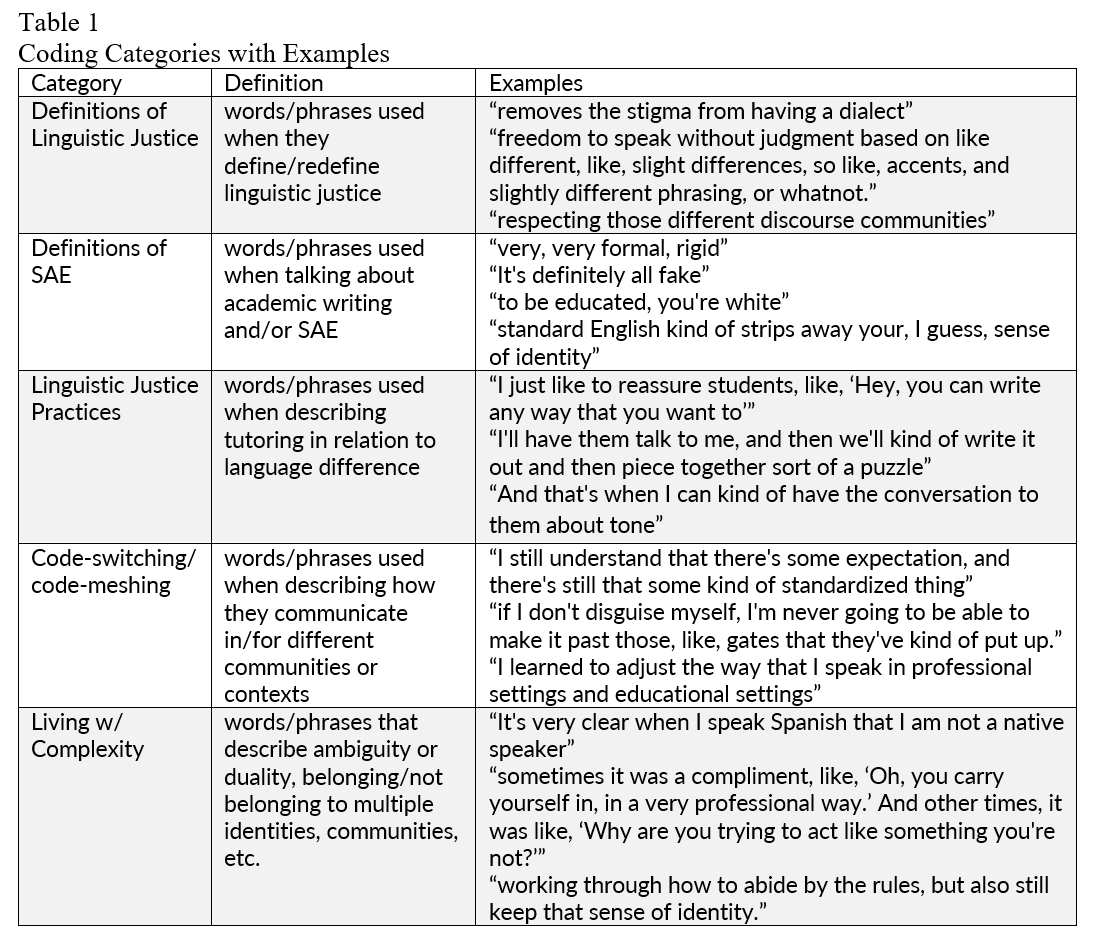

After interviews were transcribed and de-identified, Erin re-joined the process and coding was done collaboratively in multiple rounds. As a way to let tutors’ voices drive our analysis, we chose to focus first on in vivo coding, which uses the words and phrases of participants for codes (Saldaña). Initial codes included words that tutors used frequently in their interviews, which we then grouped into categories. For example, all three tutors used words like “connect” and “disconnect” when talking about communities (language we did not introduce in our questions). We grouped those uses of “connect” and “disconnect” with phrases like “biracial but doesn't look biracial” and “I've traded my ability to speak to my community” into a category that included descriptions of ambiguity or duality in identities. The table below shows the five categories we found early in our coding process with definitions and some brief examples from the interviews. Through identifying these categories and subsequent rounds of coding, themes emerged that, for us, raised questions about the multiplicity of identity, especially regarding relationships and authenticity as pertinent factors of linguistic choice, as well as the understanding, challenges, and execution of linguistic justice.

Results

This section explores key themes we identified: Multiplicity of Identity—encompassing identification and belonging, multilingualism and code-switching, and authentic voices—and Linguistic Justice Practices. These themes align with our overarching goal of showcasing the necessity of contextualizing and deepening our understanding of the nuances of our tutors' identities. By examining these dimensions, we aim to extend conversations about linguistic justice in writing centers, shedding light on the complex interplay between students' identities and their relationships with language—an aspect often underrepresented in current literature.

Multiplicity of Identity

It became apparent early on in our interviews how each tutor’s unique life experiences affected their relationship—practice and understanding—to language, and thus how they internalize linguistic justice and practice it in the writing center.

Identification and Belonging

All three tutors are traditionally-aged undergraduate students (18-24) and identify as BIPOC, two of whom are multiracial. Vanessa (she/her) is a sociology major and poet, who has worked for the writing center for one year and identifies as African American. Redwood (they/them), who has also worked in the writing center for a year and is an engineering major, described themselves as “biracial but doesn't look biracial;” they consider themselves to be part of the Hispanic community and are also half white. Serenity (she/her) classifies herself as “Asian and of Hispanic descent,” specifically being Filipino, Chinese, and Guatemalan. She is a business major who has worked in the writing center for two years.

When discussing the racial or ethnic communities each tutor identified with, they also noted how their language use was intrinsically tied to their acceptance within said community. In other words, they made a distinction between identifying as part of a community and actually belonging to, or being accepted, by it.

Vanessa

And if you're African American at UC Merced, then you have to act like it. You have to ascribe to the perspectives of what an African American person is. And I found that I couldn't necessarily always participate in black spaces because of that expectation.

Vanessa’s statement exemplifies her complex reality that being a particular race or ethnicity does not necessarily equate to her feeling a sense of belonging or connection to those communities.

Serenity

So, like, when it came to languages, like, I wasn't Hispanic enough, because I didn't speak Spanish, or because they didn't do like Hispanic things…And the same with like, like, Asian, like, I don't look Asian, I don't speak any Tagalog, Kapampangan, nothing. So, I couldn't, it was a huge disconnect.

Redwood

So, because I know how to speak Spanish, I've been able to kind of integrate myself within, like, the Hispanic community. I've gotten to really interact with a lot of, like, people part of older generations.

Serenity and Redwood highlight how language can serve as either a barrier or a bridge to their ethnic communities. Like Vanessa, this illustrates how they see their identities as not determined by simply being a certain race or ethnicity, but often by feeling they belong to it.

Multilingualism and Code-Switching

All of the tutors have varying levels of multilingualism, meaning varying levels of speaking and/or understanding multiple languages, with each having some relationship to Spanish. Vanessa, despite not being Hispanic, explained her relationship to Spanish as such: “I also understand Spanglish. I grew up in a community where it was predominantly Hispanic and Latino. And so I kind of learned how to understand Spanglish.” Serenity expressed a complicated relationship with Spanish because the version she learned in school did not allow her to fully communicate or connect with her Guatemalan family. She explained:

English is my first language. And my mom didn't really, like, she talked sometimes in Spanish. But when she's talking to me, she talks in English. So, I didn't learn any—I didn't learn Spanish from my family. I learned it in school…And then my mom's side of the family, only my mom really speaks English. So, there was like this huge pressure to speak Spanish, but they speak a different Spanish than in my Spanish class, because in school, they'll teach you international Spanish. But my mom's side of the family, they're all in Guatemala.

Redwood does not go into depth about their relationship to Spanish, but as expressed previously, they seem to have a positive relationship with Spanish in the sense that it has allowed them to successfully integrate into the Hispanic community.

In addition to Spanish, each tutor touched on how their families and extended home communities also used different dialects. Vanessa noted how she does not use African American Vernacular English (AAVE) when she speaks; instead, her natural talking voice, or discourse, reflects elements of SAE. However, her discourse would often elicit critique. She explained, “[My family is] like, ‘Why don't you just say it the way we say’...And, like, friends would be like, ‘Oh, you speak proper?’ or, ‘You speak white?’”. Similar to Vanessa, some of Serenity’s home community speak a dialect of Tagalog called Kapampangan. Unlike with her Guatemalan family, her not knowing Kapampangan did not lead to a disconnect with her family due to the prevalence of English in the Philippines. Redwood notes comfort with the dialect of English their white family uses, stating they are “pretty familiar with, like, Southern lingo just because of, like, that white side of my family.” Each tutor’s description of their languages was intertwined with relational experiences.

The tutors pinpointed the various spaces, either academic or home, where they transition between different linguistic codes (i.e., “academic” language). For example, Redwood described speaking Spanish at home as well as in the UWC when working with bilingual students. Their understanding of code-switching/meshing extended beyond just their use of it, exemplifying their rhetorical awareness in how they shift codes depending on context, audience expectations, and their own intentions.

Redwood

I mean, unfortunately, for example, if I'm trying to get, I am trying to get into grad school. If I want to get in there, I do, unfortunately, kind of have to disguise myself in a sense. Because if I don't, unfortunately, if I don't disguise myself, I'm never going to be able to make it past those, like, gates that they've kind of put up.

Vanessa

I think that we're all able to have a sense of individualism in the way that we speak and the way that we communicate with each other in the writing center, because it's such a comfortable space. And because we are so diverse, we don't have that same expectation that everyone needs to talk the same way.

Serenity

It's definitely all fake…And so when it comes to academic writing, it just feels like, okay, but like, what would they expect this to sound like?...It kind of depends on the context. Again, I'm still, when I write to things, I still understand that there's some expectation, and there's still that some kind of standardized thing…But, definitely, what I like doing specifically is I like using it ironically, or like I weaponize it. So, I'll talk. So, this is like one of my, like, when I was saying, like, oh, I know how to, like, one of my Englishes is I can bully professors…I'll purposely, like, use casual language in emails to like professors even though everyone's like, ‘Oh my god, I'm emailing professor, it has to be professional.’

Contextualized by the tutor’s narratives, it becomes apparent how relational and rhetorical motivations primarily define how and why these tutors use their own linguistic repertoires. Thus, these observations provide insight on why these tutors may choose, or not choose, to use or promote certain linguistic choices during sessions.

Authentic Voices

Apparent within their interviews is a distinction of the use and purpose of SAE where it is seen as a dialectic variety that must be used to be accepted in academic spaces, as exemplified by how Redwood described it as a necessity for entering graduate school.

Because writing center work is as much about discourse and rapport as it is about helping students with their academic writing, it’s important to acknowledge tutors’ personal, non-academic discourses. This conversation on discourse, or personal voice and authenticity, emerged within Vanessa’s interview, in which she described how SAE, and the general “white” language of academia, greatly influenced her natural discourse. She explained:

So sometimes I feel like a bit of my identity has been kind of taken away and replaced with something else. And in a way where, like, I naturally no longer speak in vernacular, African American Vernacular English, as often, but I understand it and so, like, since I was young, I kind of always tried to speak more proper in the eyes of educational institutions and that has kind of, like, kind of, I've traded my ability to speak to my community to speak to larger audiences that way.

When responding to a later question of whether the English she was taught in school has influenced the way she speaks:

I, growing up, as I mentioned, also, that I talked pretty proper, I read a lot from a young age, and I accustomed my speaking to the Standard English or Standard Academic English or something. In that way, I accustomed myself to that, and people told me that I spoke white, or it didn't sound black, or I talked white, or, you know, like, there was this trading identity that I had based off of the way that I spoke or, you know, people expected more or less of me depending on how I spoke.

When Vanessa spoke about how one has to talk black to be black, she said she felt her voice was authentically her own despite it having been “taken away and replaced with something else.” She elaborated:

I would say I own it, there's an element of authen-authenticity to it. Honestly, even though I do speak in a way that's kind of, like, heavily formalized to a generalizable audience, I still mean and emphasize everything with the way that I talk. So, because my prose is very accustomed to Standard Academic English, I still have in the content of what I speak, my identity.

Throughout her interview, Vanessa demonstrated an acute awareness of the influence SAE had on the development of her natural discourse.

Linguistic Justice Practices

Each of our three tutors frame linguistic justice in slightly different ways and have different approaches, at least based on the examples shared in their interviews, to practicing linguistic justice in their roles as writing tutors. The descriptions all three gave of their work in the writing center and their goals for working with students parallel the ways in which they define “linguistic justice.”

To Redwood, linguistic justice is about the "respect and acknowledgement of different types of writing within different communities" and avoiding "discrediting or...ignor[ing] people's form of writing and their form of speaking.” When framing linguistic justice within the context of their work in the UWC, they say, "by implementing more linguistic justice practices, it will help our students just feel more comfortable with the concept of writing and happier with what they're producing."

Redwood’s efforts to make sure the student is “happier with what they’re producing” is evident in one example they shared. In the session they described, the student they were working with had received some negative feedback from a professor, specific to the tone or level of formality of the student’s work. Redwood described asking the student to talk through their ideas, writing down what they heard from the student, and then working with the student to put together the "pieces" while still keeping the student's "overall message." At the end of the session, Redwood said, “I could definitely tell that she was still upset with the professor. But I think it did help to kind of still keep her sense of voice while still kind of meeting that middle ground of the professor. So, compromise.”

Redwood further described their approach to linguistic justice in tutoring sessions by sharing an example of working with a student whose first/native language is Spanish. They said:

I think, to be able to respect their, kind of, how they, I guess, they approach writing through their native language, while also still trying to adhere to academic writing is a big part of our job…but we also kind of have this, like, job where we also have to make sure they're adhering to what their professors want. So, it's like a kind of difficult barrier, I guess, that we kind of have to learn how to traverse. And I think that's a big part of me respecting all my students’ kind of specific languages. So even though we'll do this session in Spanish, I will kind of try to help them relate kind of the grammar differences between Spanish and English and, kind of, trying to help them navigate that. So that when they're doing future papers, they know how to navigate that on their own while still keeping their own sense of, like, voice and ideas.

A central part of Vanessa’s understanding of linguistic justice is that there is “advocacy” in it. She elaborated on this, saying that linguistic justice is about “being able to uplift voices and…free dialects from an expectation.” She elaborated:

[Linguistic justice is] where you kind of, like, allow people to speak the way that they naturally speak and the communities they naturally speak in, and they're allowed to kind of, like, bring that into other spaces in other communities…Linguistic justice helps remove that expectation that if you speak a certain way, you must ascribe to a certain cultural identity or, or whatever you're saying the way that you speak it. Like, it removes the stigma from having a dialect, and a different way of speaking, even in academic institutions.

Vanessa thinks that linguistic justice is important for writing centers and writing tutors to uphold. When speaking about being a tutor in the UWC, Vanessa said:

We're not necessarily here to tell students what to think and how to write. We're just providing them the tools necessary to get their ideas out…[we] want to help students embrace their level of understanding and writing without the fear of being judged or persecuted for the way that they speak and how they communicate their ideas.

In practice, what this looks like for Vanessa is “stressing how, like, powerful [students’] words are.” She describes talking with a student like this:

I tell them as long as your, your statements, as long as you can ascribe significance and a place that they have within your writing, then they should be in there. If you can understand why you wrote that sentence, you have power in your words, because there's a significance to each and every sentence in your writing. And that can contribute to a strong overall paper…Your words are—doesn't matter how you say it, or where you say it, as long as it's powerful in that statement.

Serenity defines linguistic justice as “the freedom to express someone like oneself without…someone telling you you're wrong or the way that you're talking is wrong.” She frequently referred to SAE and academic writing as “fake” and that learning this “fake” academic language is a way for a student (herself included) to “fight for their space.” She said, “[we] have to mimic what's already there, almost. So just, kind of, pretending like we talk like this, so we can have our space.”

As a tutor, Serenity sees linguistic justice as something that helps her “focus on the person instead of the writing.” She described folding “small conversation[s]” into her sessions because:

Even if it's just, like, a small conversation, building in linguistic justice, or kind of mentioning it, even just talking about that can really trigger something or, like, cause a slight change of perspective compared to the one that we've been force fed since elementary school.

In one specific example she shared, she talked about working with a student who was “really caught on one word,” where the student was saying things like, “it just doesn't sound professional enough” and “I, like, sound like a first grader.” In response to this student, Serenity described a conversation in which she explained that “big words” aren’t always necessary and that “normally, it's better to just use more simple words and make sure that your intention is clear than, kind of, trying to use more professional words.”

Serenity sees value in “baby steps” like this conversation in sessions. She said, “It’s sometimes about just doing quick mentions” and not going into “the history and why you shouldn't say that word for linguistic justice reasons for 15 minutes.” She further explained her view of linguistic justice in tutoring as:

I think, kind of opening up the door for places that aren't familiar is a big enough step, which probably might not be popular. Some people want, like, linguistic justice, like, right there. And I just know, like, that's not going to happen, especially people who have been so used to the standard and so fed the standard that a whole new worldview, or a whole new, kind of, concept is really, really hard to come by. I think this kind of ties into my personal thing of unlearning, and how difficult it is to unlearn something you've been normalized to, especially the older you are, like, the longer you've been exposed to some tradition. So, baby steps is fine.

Through reflection, each tutor defined the use of SAE as a second, learned language that often clashes with a writer’s voice or true meaning. In turn, we see them making decisions within their sessions that take into consideration a variety of factors: the student’s needs in that moment, their understanding of the necessity and influence of SAE on the work at hand, and their own approach to navigating the parameters of justice-informed work. The reflections provided by these tutors display a kind balancing act, one that is informed by complex identities and nuanced relationships to language.

Discussion

The excerpts we chose to highlight were a result of in vivo coding and, in turn, the co-creation of meaning throughout the coding process. It was in this process that we began to make meaning and interpretations of our tutor’s shared stories. Overall, we found that these tutors’ self-perception of their whole and linguistic identity played a major role in how they perceived and enacted linguistic justice. What we especially wish to note in the following section is how the complex multiplicity of tutors’ identities, shaped by relationships with various communities, is necessary to consider when trying to enact linguistic justice work in our centers. Conversations with our tutors have shown us that linguistic justice work is deeply personal and contextual.

Identification and Belonging: The Influence of Primary and Secondary Discourse Communities

Self-identification seems to be more than simply being, but rather belonging. This sense of belonging to a community seemed to influence the tutor’s perceptions of language. The tutor’s relationship to the language of their communities, including secondary discourse communities– those that are typically entered as opposed to born into (primary)–played a significant role in how the tutors understood and practiced linguistic justice.

Redwood’s approach to tutoring comes, at least in part, from understanding language as a means of access. Redwood, who is a STEM major and at one point in the interview described how “STEM hates all things justice,” spoke of wanting to help students find a balance between what the student wants to say and the expectations of the professor. Coming from a field that, as we understood Redwood to perceive it at least, has little room for pushing against those expectations, Redwood doesn’t necessarily encourage students to push against expectations of SAE; rather, they look for a middle ground or, in their words, “compromise.” Redwood explained that speaking the language of one of their primary discourse communities, Spanish, allowed them to connect with members of this community. We suspect that language ability was something valued by this community which in turn may have led to a positive sense of belonging. Alternatively, to enter into the desired academic space, Redwood described a need to disguise themselves in order to “make it past those, like, gates” of graduate school. It appeared to us that Redwood understood language as an important factor for accessing and being accepted in certain communities, thus influencing how they enacted linguistic justice. Redwood’s strategy of “compromise” in their tutoring sessions, and personal writing endeavors, seems to have been influenced in part by a value of the academic discourse community: the necessity to “compromise” oneself in order to enter that space.

Vanessa’s approach to tutoring is also shaped by layers of experiences with language, including her experience with writing poetry. She talks about poetry helping her understand the power of language; she said it is “powerful” to have “a way to get, like, people to understand your inner world and what you're thinking…and that is something that is found a lot in poetry.” She described applying this concept in other writing as well, and we can see it reflected in how she talks about working with students in the writing center. She explained, “If you can understand why you wrote that sentence, you have power in your words, because there's a significance to each and every sentence in your writing. And that can contribute to a strong overall paper.” The message of empowerment that she shares with students in sessions and her goal of “help[ing] students embrace their level of understanding and writing without the fear of being judged or persecuted” is heavily informed by an understanding of the power of language that she attributes to her experiences with poetry. It appeared to us that the way Vanessa perceived her role as a tutor was influenced, in part, by her relationship with language as a poet, which in turn translates into how she talks about language with her students (“power in your words”).

What we’ve observed is that our tutors’ conceptualization and approach to tutoring has been influenced by their conception and relationship to language, which in turn was shaped by the many discourse spaces they move through. Unsurprisingly, they reflected “hybridity, intersectionality, and multiplicity” (Klotz and Whithaus 73) in both the conception of their personal identity as well as their discourse. In other words, their lived experiences have predisposed, and thus taught, them what it means to recognize, navigate, and perhaps feign acceptance into various discourse communities, both academic and of the home. As practitioners seeking to implement and encourage linguistic justice work in our writing centers, we need to be careful not to generalize our student’s identities, both with language and in regard to their perception of self. Otherwise, we risk potentially applying stereotypes or expectations that may have detrimental effects. We have to remember that our undergraduate tutors are often still in the midst of critical self-discovery and identity development.

BIPOC and, doubly so, multiracial individuals like Redwood and Serenity, often struggle with identity development. The multiplicity of our tutors’ identities reflect a sense of self that is more prone to being in flux. Kerry Ann Rockquemore et al. explain, “Identity development for mixed-race people is neither in a predictable linear fashion, nor does it have a single endpoint” (3). Meaning, mixed-race individuals often change how they identify themselves throughout different stages of their life. Identity and belonging are also called into question when one’s parent and/or ethnic group is invalidated due to not looking or sounding a certain way (Harris). Our tutors shared this reality. Vanessa was chastised by her home communities because she “talked white” and not in AAVE. She poignantly reflects on the difficulty of being accepted by the black community at UC Merced, despite being black, because she didn’t correctly perform what it meant to be black. Similarly, Serenity struggled with the negative stigma of looking like she could speak Spanish fluently while not being able to. As remarked earlier, Redwood noted that, although they are someone who “doesn’t look biracial,” they have been able to connect with Spanish-speaking communities due to their multilingualism.

Considering students' identity development and nuanced experiences navigating academic, social, and familial discourse communities, the predominantly white field of writing center studies needs to be cautious not to overgeneralize the identities and experiences of BIPOC students. In “Unmaking Gringo Centers,” Romeo Garcia talks about the need to expand beyond the black-white paradigm, explaining that writing center scholarship typically only discusses race in reference to blackness and with a lack of nuanced identity. He argues that “blackness in this paradigm is meant to stand for all struggles, as well as of the failure of this paradigm to account for the particularities of the experience of people of color who are not black” (39). In a similar vein, Carlos Poston, speaking from the discipline of psychology, discusses the importance of racial identity development as it opposes the “cultural conformity myth,” which presumes those of a certain race are all perceived to have had similar experiences or share common ideologies (1). This may seem like an outdated notion, but as Garcia touches on with the black-white paradigm in our scholarship, there is often a tendency to apply a monoracial, or over-simplistic, lens to the experiences of BIPOC students. For example, not all students of color are multilingual or multidialectal. There are many students of color whose primary discourse, learned from their home space, is rooted in white linguistic codes. The paradigm that Garcia mentions is one that disregards these particularities, and thus adheres to the cultural conformity myth.

Our point here isn’t necessarily to suggest that our scholarship should try to account for all identities, in all their countless, myriad complexities. Even Multiracial Critical Race Theory acknowledges the sheer impossibility of trying to account for the innumerable narratives and experiences our tutors and students bring with them when they enter academia and the writing center space (see Johnston-Guerrero et al.). Rather, the foregrounding of our tutors’ narratives is to emphasize to writing center practitioners how essential the specific context of tutors’ identities and writing center demographics are to the teaching, talking, and enactment of linguistic justice.

Multilingualism and Code-Meshing/Switching: The Impossible Divide between Language and Relations

It became apparent within the interviews that each tutor’s discussion of their linguistic identity coincided with, unprompted, a discussion of relations, in turn highlighting that multilingualism does not exist in isolation of one’s identity. Similar to racial and ethnic identification, one’s perception of their linguistic abilities goes beyond mere mastery. The idea that the tutor’s understanding of language as relational influenced the way they chose to, or not to, utilize a strategy like code-meshing/switching. This is why we encourage writing center practitioners to more deeply recognize the reality of language as something deeply relational.

Although our tutors understood the technique and rhetorical motivation of a strategy like code-meshing, it was not something that was embraced by any of the tutors. Vershawn Ashanti Young’s "Should Students Use They Own English” is often cited to exemplify and teach code-meshing as both a rhetorical and linguistic justice strategy that aims to combine oral and written discourses. Some contexts, like that of Karen Keaton Jackson and Amara Hand’s writing center, are “pro-code-meshing” (52) because they’re at an HBCU where students are more “likely to have student populations who are naturally fluent speakers of African American Language” (49). Alternatively, consider what we may be asking Serenity, who isn’t comfortable using Spanish; Redwood, who likes to stick to disciplinary expectations; or Vanessa, who is black but doesn’t use AAVE, when we encourage them to teach their students to code-mesh or write against academic expectations during their sessions. Young’s piece on code-meshing may be difficult for our tutors to fully relate to and/or enact. Once again, we are not suggesting that practitioners must decode all the nuances of their tutor’s identities. Rather, we hope that the sharing of these tutors' narratives sheds light onto the possibility of why linguistic justice, or other anti-racist pedagogies, may feel hard to enact within sessions, as was the case with the tutors observed in Thompon’s study.

Authentic Voices: Considering the Reality that All Our Languages Are Our Own

Not just how we use language, but how others perceive us based on our language use, often plays an integral role in the development of our identity and perception of self. Vanessa describes an important, and not uncommon, experience for many BIPOC individuals; her discourse, her voice, has become one that has been deeply influenced or enmeshed with the white linguistic codes that make up SAE. A primary discussion within linguistic justice is the need to ensure a student's authentic voice and identity has a place within academic spaces and scholarship. Considering this, what, then, is Vanessa’s authentic voice?

Jacqueline Jones Royster’s piece, “When the First Voice You Hear is Not Your Own,” makes an important comment about the authenticity of the voice of BIPOC persons:

What I didn't feel like saying in a more direct way, a response that my friend surely would have perceived as angry, was that all my voices are authentic, and like bell hooks, I find it "a necessary aspect of self-affirmation not to feel compelled to choose one voice over another, not to claim one as more authentic, but rather to construct social realities that celebrate, acknowledge, and affirm differences, variety" (12). Like hooks, I claim all my voices as my own very much authentic voices, even when it's difficult for others to imagine a person like me having the capacity to do that…In both instances, genius emerges from hybridity, from Africans who, over the course of time and circumstance, have come to dream in English, and I venture to say that all of their voices are authentic. (37)

SAE can be considered a dialect in and of itself that is then imposed upon students in academic settings. What is not often discussed, however, is the reality that one can own this dialect imposed upon them. SAE is as relational as other dialects and languages and similarly affects our sense of belonging to certain communities. For Vanessa, SAE has become a part of her dialect, in which her voice is still authentically her own: “I would say I own it.”

Standard American English, like other dialects and languages, was depicted by Vanessa and Royster as an integral part of oneself, influencing both identity and belonging. When we teach tutors—students—that SAE simply equates to something negative, we disregard the reality that SAE, while it has “taken away” and disrupted our tutors’ voices, is also something that has become deeply intertwined into their expression of self, their discourse. The enculturation of SAE in academic settings “is an act of violence” (Lockett), and so a goal of linguistic justice is to change this, and to put a stop to experiences like Vanessa’s or Royster’s where SAE deeply imbued itself into their discourse. Yet the reality for many students, white and BIPOC, monolingual and multilingual alike, is that our discourse is, inherently and simultaneously, varied and authentic. This is not to say that SAE isn’t harmful and that we shouldn’t try to dismantle the hold it has over academic and professional spaces. Rather, we must be more cognizant of how we discuss SAE in our writing centers and in the field more broadly. Thus, in these discussions of SAE, writing center administrators attempting to discuss linguistic justice in their centers and with their tutors need to be aware of the reality that our discourse may be made up of dialects with opposing histories or ideologies. Yet, Vanessa, like Royster, claims all the varieties, influences, and experiences of her voice when she says, “I still have in the content of what I speak, my identity.”

Implications

Considerations of Labor

Research on identity development presents how one’s self-identification influences their comfort and participation within certain movements; Victoria Malaney-Brown argues that “society’s monoracial perceptions or labels that [multiracial students] are ‘not enough’ [make] them self-conscious, and at times doubtful, of how they could contribute to racial justice movements” (154). Both Serenity (multiracial) and Vanessa (monoracial) expressed these sentiments of being “not enough.” Despite that, we see that they have chosen to engage in the labor of linguistic justice in their tutoring practice. As a field, however, it is important to note that when we encourage linguistic justice work in our programs, we also recognize it as emotional and deeply personal labor, because it asks our tutors to engage in potentially taxing or traumatic work.

For example, when faced with the predicament of how to teach grammar while adhering to linguistic justice within the context of tutorial sessions, Esterly et al. say to “introduce the writer to the concept of Standard English and dialectical differences, and to remind the writer that they have choices” (49). This ask may not be as easy as it seems, however. Consider how a tutor is to discuss “dialectical differences” when they may be in the midst of navigating the “disconnect” between their own identity and home communities, as Serenity was. When we ask our tutors to take up the labor of linguistic justice, work deeply entrenched in the self, our traditionally-aged undergraduate students may still be in the midst of discovering and defining themselves. Certainly, not every student may suffer from identity or community disconnects rooted in linguistic differences. Regardless, if we aim to encourage our tutors to engage in acts that are deeply connected to race and identity, we need to do the labor of acknowledging these intricacies. And to do that, we need to extend our conversations beyond theory and explore more practice-based research that represents a variety of contexts and that centers the voices and experiences of the tutors engaged in this work.

That being said, we don’t need to know the depth of our tutors’ pasts in order to be respectful of this kind of labor. As Bethany Mannon notes, emotional labor is central to the work of writing center tutors but is often not addressed in our scholarship as a skill that can be learned and practiced. When we encourage tutors to engage in linguistic justice work, work that may be drawing on fraught emotions for both the writer and the tutor, we are adding to an already notable cognitive and emotional load. It seems crucial, then, to recognize this work as labor—and to name it as labor in explicit ways that may help tutors frame their own capacity for engaging in linguistic justice as well as help writing center practitioners frame their expectations for tutors engaging in that labor.

Considerations of Nuance

If emotional labor is a skill that can be learned, then we have to acknowledge, for ourselves and for our tutors, that it will have its own complex and messy learning process that will inevitably interact with all of the other developmental processes tutors are engaged in. Redwood and Serenity both shared examples of their efforts to “apply” linguistic justice in tutoring sessions where the students’ emotions were clearly at the forefront of the session.

In Redwood’s story, it was a student who was “upset with the professor,” and in Serenity’s story, it was a student who was worried about “sound[ing] like a first grader.” While neither identify the work they did in these sessions as “labor,” let alone emotional labor, both Redwood and Serenity described navigating those sessions in very different ways, with Redwood aiming for “compromise” and Serenity explaining to the student that sometimes simple language is better than a “fake” expectation of “professional” language.

Whether this difference in approach is related to different stages of their learning processes, different “levels” of practice like those Pawlowski outlines, or some other invisible difference in dispositions these two individual tutors may hold doesn’t matter. What does matter is how we support these tutors in engaging in that labor—and how we avoid judging either for being more “right” than the other in their approach. In other words, if we want to implement linguistic justice, we need to do the work of learning how best to support our specific tutors, in all their complexities, within our specific contexts. And to do that, we need more scholarship that is grounded in the messy, evolving realities of tutors’ everyday lived experience and practice.

Considerations for Implementation

Contextualization is essential for the actualization of linguistic justice work in our writing centers. That being said, we cannot offer universal strategies as, again, effective practice and learning require curating justice education to individual tutors and contexts. We also want to acknowledge that, due to conditions shaped by systemic inequities and political climates, some practitioners are positioned with more flexibility, sway, or autonomy than others. We believe that writing centers do have an important role to play in the pursuit of linguistic justice within their specific institution; however, that role fluctuates based on the writing center’s positionality. As we noted with how our tutors perceive and conduct linguistic justice, there is no correct way to engage in this work. A center has not failed in the implementation of linguistic justice if, for example, their tutors do not code-mesh in practice or the center lacks a public-facing linguistic justice statement. With this in mind, what we offer are starting points that practitioners can adapt based on the nuance of their centers. Though directed at administrators, we believe tutors can also initiate these practices and conversations.

Some practical considerations for implementation:

Start with the tutors. Introduce conversations about linguistic justice by inviting tutors to reflect on their own experiences with language and identity. Consider how you can create opportunities for them to share these reflections with one another, including options for sharing anonymously to encourage openness and vulnerability.

Listen with intention. Take a step back—both literally and metaphorically—whenever possible. Show tutors that their voices are not only being heard but genuinely valued. Consider how you can demonstrate your commitment to their lived experiences, thought processes, and evolving identities.

Keep the dialogue open. Acknowledge that this work is an ongoing process of learning and unlearning for tutors and administrators alike. Consider how you can build in multiple opportunities to revisit conversations about linguistic justice, allowing ideas and perspectives to deepen and evolve over time.

Create shared foundations. Collaborate with tutors to build a library of resources—readings, media, frameworks—about linguistic justice, language and power, and context-specific experiences with language. Consider how you can ensure a range of entry points, creating a living collection that reflects diverse voices, contexts, and experiences.

Name the labor. Be explicit about the expectations and emotional complexity this work may involve. Consider how you can recognize the different ways tutors may choose to engage or not engage and create space for those variations. Honor the time, energy, and emotional labor that come with this ongoing work.

Final Thoughts

While sharing the experiences—the voices—of BIPOC tutors to the field’s conversations about linguistic justice practices was a central motivation for our project, it was inevitable that our own perceptions of that work would be influenced by what we learned throughout the process of this project. We knew these tutors had stories to tell, and that these stories would be personal and powerful. We believe, even more now, that the nuances of our tutors’ identities and experiences, as well as that of our writing centers and institutions, must deeply inform the ways in which we engage in linguistic justice work. When we take up this work, both individually as practitioners and wholly as a field, we should seek to acknowledge the complex intersections of languages, identities, and communities as well as attend to the labor involved for those who are asked to “enact linguistic justice.”

We don’t need to know it all, but we must listen. And to do that, we must continue to engage in these conversations with our tutors and with each other. What we hope more than anything is that our small project encourages others to talk to their tutors—to listen rather than just theorize—to continue these conversations with the field, and in those conversations, create space for nuance and how they engage in that work. This work is complex, messy, and sometimes contradictory, but we know, from listening to our tutors, that it is vital. And we’re still learning how to do it better.

With that in mind, we’d like to close with the voices of our tutors:

“Because to some people, [linguistic justice is] the first thing that they need to fight for in the morning. And for other people, it's not, and it is a privilege to do that.” - Serenity

“But I think it's gonna take a lot of people and a lot of effort from within to really make any sort of progress.” - Redwood

“Honestly, at some point, I just kind of like, I realized how I speak doesn't really matter; what I speak about does.” -Vanessa

Works Cited

Baker-Bell, April. Linguistic Justice: Black Language, Literacy, Identity, and Pedagogy. 1st edition., Routledge, 2020.

Camarillo, Eric C. "Dismantling Neutrality: Cultivating Antiracist Writing Center Ecologies." Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, vol. 16, no. 2, 2019, https://www.praxisuwc.com/162-camarillo.

Center for Institutional Effectiveness. “Undergraduate Enrollments.” University of California Merced, cie.ucmerced.edu/undergraduate-enrollments. Accessed 19 July 2024.

Chiseri-Strater, Elizabeth. “Turning in upon Ourselves: Positionality, Subjectivity, and Reflexivity in Case Study and Ethnographic Research.” Ethics and Representation in Qualitative Studies of Literacy, edited by Peter Mortensen and Gesa E. Kirsch, National Council of Teachers of English, 1996, pp. 115-133.

Diab, Rasha, et al. "A Multi-dimensional Pedagogy for Racial Justice in Writing Centers." Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, vol. 10, no. 1, 2012. https://www.praxisuwc.com/diab-godbee-ferrell-simpkins-101

Esterly, Zoe, et al. “Linguistic Diversity from the K–12 Classroom to the Writing Center: Rethinking Expectations on Inclusive Grammar Instruction.” The Writing Center Journal, vol. 41, no. 2, 2023, pp. 42–55. https://doi.org/10.7771/2832-9414.1940

Garcia, Romeo. “Unmaking Gringo-Centers.” The Writing Center Journal, vol. 36, no. 1, 2017, pp. 29–60. https://doi.org/10.7771/2832-9414.1814

Greenfield, Laura, and Karen Rowan. Writing Centers and the New Racism: A Call for Sustainable Dialogue and Change. 1st ed., Utah State University Press, 2011.

Grimm, Nancy Maloney. Good Intentions: Writing Center Work for Postmodern Times. Boynton/Cook-Heinemann, 1999.

Harris, Jessica C. “Toward a Critical Multiracial Theory in Education.” International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, vol. 29, no. 6, 2016, pp. 795–813. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2016.1162870

Jackson, Karen Keaton, and Amara Hand. “Effectively Affective: Examining the Ethos of One HBCU Writing Center.” The Writing Center Journal, vol. 41, no. 3, 2023, pp. 38–54. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27275940

Johnson, Michelle T. "Racial Literacy and the Writing Center." Writing Centers and the New Racism: A Call for Sustainable Dialogue and Change, edited by Laura Greenfield and Karen Rowan, Utah State University Press, 2011, pp. 211-227.

Johnston-Guerrero, Marc P., et al. Preparing for Higher Education’s Mixed Race Future: Why Multiraciality Matters. 1st ed., Springer International Publishing AG, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-88821-3

Klotz, Sarah, and Carl Whithaus. “Gloria Anzaldúa’s Rhetoric of Ambiguity and Antiracist Teaching.” Composition Studies, vol. 43, no. 2, 2015, pp. 72–91. https://www.jstor.org/stable/45157100

Lockett, Alexandria. “Why I Call it the Academic Ghetto: A Critical Examination of Race, Place, and Writing Centers.” Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, vol. 16, no. 2, 2019. https://www.praxisuwc.com/162-locket

Malaney-Brown, Victoria K. “What Is Multiracial Consciousness? Developing Critically Conscious Multiracial Students in Higher Education.” Preparing for Higher Education’s Mixed Race Future, edited by Marc P. Johnston-Guerrero, et al., Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 125–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-88821-3_7

Mannon, Bethany. “Centering the Emotional Labor of Writing Tutors.” The Writing Center Journal, vol. 39, no. 1/2, 2021, pp. 143–68. https://doi.org/10.7771/2832-9414.1962

Morrison, Talisha Haltiwanger, and Deidre Anne Evans Garriott, editors. Writing Centers and Racial Justice: A Guidebook for Critical Praxis. Utah State University Press, 2023.

Pawlowski, Lucia. "Introducing Linguistic Antiracism to Skeptics: A Scaffolded Approach." The Peer Review, vol. 8, no. 1, 2024. https://thepeerreview-iwca.org/issues/issue-8-1-featured-issue-enacting-linguistic-justice-in-through-writing-centers/introducing-linguistic-antiracism-to-skeptics-a-scaffolded-approach/

Perryman-Clark, Staci M. "2022 Call for Proposals." Conference on College Composition and Communication, Conference on College Composition and Communication, 2021. cccc.ncte.org/cccc/call-2022

Poston, W. S. Carlos. “The Biracial Identity Development Model: A Needed Addition.” Journal of Counseling and Development, vol. 69, no. 2, 1990, pp. 152–55. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.1990.tb01477.x

Rockquemore, Kerry Ann, et al. “Racing to Theory or Retheorizing Race? Understanding the Struggle to Build a Multiracial Identity Theory.” Journal of Social Issues, vol. 65, no. 1, 2009, pp. 13–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.2008.01585.x

Royster, Jacqueline Jones. “When the First Voice You Hear Is Not Your Own.” College Composition and Communication, vol. 47, no. 1, 1996, pp. 29–40. https://doi.org/10.2307/358272

Saldaña, Johnny. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. 3E., SAGE, 2016.

Schreiber, Brooke R., et al. Linguistic Justice on Campus: Pedagogy and Advocacy for Multilingual Students. 1st ed., Channel View Publications, 2021.

Seidman, Irving. Interviewing As Qualitative Research: A Guide for Researchers in Education and the Social Sciences. 5th ed., Teachers College Press, 2019.

Shapiro, Rachael, and Missy Watson. “Translingual Praxis: From Theorizing Language to Antiracist and Decolonial Pedagogy.” College Composition and Communication, vol. 74, no. 2, 2022, pp. 292–321. https://doi.org/10.58680/ccc202232276

Students’ Right to Their Own Language, special issue of College Composition and Communication, vol. 25, 1974, pp. 1-32. https://www.jstor.org/stable/i215150

Thompson, Faith. “‘How to Play the Game’: Tutors’ Complicated Perspectives on Practicing Anti-Racism.” Praxis, 2023, www.praxisuwc.com/211-thompson.

Tucker, Keli, and Emily Bouza, editors. Issue 8.1: Special Issue – Enacting Linguistic Justice in/through Writing Centers, vol. 8, no. 1, The Peer Review, 2024. thepeerreview-iwca.org/issues/issue-8-1-featured-issue-enacting-linguistic-justice-in-through-writing-centers/

Villanueva, Victor. “Blind: Talking about the New Racism.” The Writing Center Journal, vol. 26, no. 1, 2006, pp. 3–19. https://doi.org/10.7771/2832-9414.1589

Young, Vershawn A. “Should Writers Use They Own English?” Writing Centers and the New Racism: A Call for Sustainable Dialogue and Change, edited by Laura Greenfield and Karen Rowan, Utah State University Press, 2011, pp. 61-72.