Praxis: A Writing Center Journal • Vol. 22, No. 3 (2025)

Evolving Perceptions of GenAI Writing Tools: Why Writing Centers Should be GenAI Pioneers

Nathan Lindberg

Cornell University

nathanlindberg@cornell.edu

Abstract

Generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) writing tools (e.g., ChatGPT, Claude, Perplexity) have emerged so quickly that their impact on writing centers is not well understood. This article presents data from two studies that were conducted in 2023 and 2024. One consisted of surveys of writing center administrators and related parties. The other was surveys and interviews of students. In 2023, administrators and related parties saw the new technology with suspicion and concern, while students embraced it. However, after a year, the narrative tended to merge. Administrators’ and related parties’ concerns diminished while students became less enamored. Both groups viewed GenAI writing tools as powerful but limited, requiring skill to use. Already some writing center directors are incorporating GenAI writing tools into their programs. This article argues writing centers can even go further, pioneering the use of the new technology.

In Graham Stowe’s September 2023 blog post, he grappled with the impact of generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) writing tools (e.g., ChatGPT, Claude, Copilot) on the writing center. He assumed students would want help using the new tools and reviewing texts written with them. But Stowe noted that at the time there had not been enough IRB-approved studies that could guide how to approach the tools. He concluded, “The best course of action is to wait and see.”

A lot has changed since then, including that research has been conducted. This paper presents data from two studies conducted in 2023 and again in 2024. The first is a survey that gives evidence that writing center administrators and interested parties (e.g., faculty, staff) were initially wary of GenAI writing tools but felt less negative or even positive about them after a year. The second study consists of surveys and interviews of international graduate and professional students, who were quick to embrace the new technology, sometimes using it as a proxy for tutoring. However, after the initial luster wore off, some became disenchanted and even came back to the writing center, seeking human help.

The two perspectives can be seen as merging, finding the technology neither an existential threat to the writing center nor a replacement for it, but instead a powerful but limited tool that requires skill to use effectively. As Stowe predicted, clients are bringing in GenAI-created text, and some directors have accepted the technology and are already incorporating the tools into their programs, making them part of tutor training and sessions.

The acceptance of the tools is not surprising. At writing centers, we have always worked with new technologies (Bryan). Today, we are in an advantageous position to work with GenAI in multiple ways. We have the knowledge and experience to ensure students don’t lose their voice to machines. We can raise awareness that GenAI can produce biased text. We can work to protect privacy. Additionally, positioned between faculty and students, we can advise on policy, striving to ensure the tools are used ethically and do not impede learning.

In this paper, I argue a further opportunity exists. Writing centers are not just in a position to accept GenAI writing tools, but they can and should lead the way in using them. These are the most powerful writing tools ever created, with many intriguing uses. We have the experience and ability to pioneer approaches that enhance existing writing strategies or even create new ones never before possible.

My Context with EAL Graduate Students

The premises in this article are an inherent part of my positionality. I teach for Cornell’s English Language Support Office (ELSO), and direct ELSO’s Writing & Presenting Tutoring Service, which works almost exclusively with international graduate and professional students, whom I surveyed and interviewed for this article. My students often write high-stakes, public-facing documents (e.g., dissertations, research articles) that form part of their reputations. Consequently, they are motivated to retain agency and to be wary of giving too much influence to GenAI writing tools. Working with these students, I do not have many ethical concerns about them cheating, i.e., having GenAI tools write their papers. However, many of these students were early adopters of GenAI tools.

Most of my students use English as an additional language (EAL), and often write with what has been called written accents; just as we speak with an accent, we write with one (Cox; Zawacki, et al.). Written accents entail more than mistakes: they contain problems that stem from the relationship between English and a writer’s first language. For example, Chinese does not have the equivalent of articles (i.e., a, an, the), so Chinese writers might fail to include articles or use them inappropriately. Other common issues include unconventional phrasing, vocabulary, and syntax, all of which are not necessarily erroneous, but make accented writing seem odd. If EAL students want to publish, they are usually required to adjust their accents to conform to North American academic standards (For more on the subject, see Lindberg, 2025).

To adjust written accents, our clients often used to make appointments with our writing service. In fact, pre-GenAI, on post-session evaluations, they consistently ranked “looking for mistakes” as their top goal. When ChatGPT 3.5 was introduced, my students quickly realized how effectively it adjusts accented writing. By spring 2024, their goal of “looking for mistakes” had dropped to a distant third, behind getting the tutor’s overall opinion and working on structure. Consequently, our writing center suffered a 31% drop in occupancy in spring 2023 and eventually declined by 60% in spring 2024.

Readers who work primarily with domestic undergrads might feel that input from international students does not apply to their situations. For example, undergrads are more likely to be developing their writing skills. If they rely on GenAI writing tools too much, they will miss learning opportunities. Thus, there is an incentive to ask these students to pause or abate their GenAI writing tool usage. However, such a request is most likely fruitless. It is more likely that future generations will grow up using these tools as an integral part of their writing process. Looking to early adopters, such as my students, can help us see how the tools are being used for authentic, public-facing writing in upper-level classes and, eventually, by faculty and in the workplace.

Review of the Literature

GenAI writing tools have become so popular so quickly that writing center scholars are still debating their impact. Some have advocated that they are just the newest technology among a long list of those that writing centers have adapted (Bryan). However, these tools are much more powerful than previous technologies. Available 24/7, with access to knowledge in all fields, and actually able to construct coherent papers, they have been touted as replacements for tutoring (Mollick; Rahman and Watanobe). Though there were early attempts to ban GenAI tools (Yadava), as of yet, teachers have no reliable way of detecting GenAI-generated text (Heaven; Terry), so such bans are difficult to enforce. Trends indicate that GenAI writing tools are only going to become more effective and ubiquitous (Graham).

In such a short amount of time, there has been a lack of IRB-approved research. There were, however, blogs on the subject (e.g. Hotson, Part 1; Hotson Part 2; Stowe; Lindberg) and a plethora of GenAI themed presentations at conferences. At the 2023 International Writing Center Association’s (IWAC’s) conference in Baltimore, a dozen events (i.e., panel discussions, roundtable discussions, individual presentations) were focused on AI—several mentioning ChatGPT by name. At the 2024 online IWAC conference, that number increased to 58, which was 38% of all events.

With this quick growth spurt, many problems have arisen. The texts that GenAI writing tools generate can look like academic writing but contain mistakes or even fabricated information (Ali and Singh). Beyond inaccuracies, teachers and students have expressed concerns that GenAI tools are negatively impacting education—even replacing humans (Shoufan). Furthermore, these tools could create a division between those who can afford the technology and those who cannot (Yan) and they may further solidify the use of colonial languages (e.g., Standard English) and the concentration of power (Madianou; Byrd).

Despite all the problems, scholars are also finding opportunities. For example, while Meyer points out that students’ voices can be lost in GenAI-writing, Wang sees this problem as an opportunity to discuss what voice entails and how it might be reinserted, raising awareness of the issues and, ultimately, leading to more controlled writing. In another example, Werse feels that relying on GenAI writing tools could negatively impact developing critical thinking, but Matas suggests that students can increase such skills by scrutinizing GenAI-written text. And though Lester argues that GenAI text carries many biases, such as gender, she also admits it can be used to make such biases salient.

Meanwhile, students are developing their own approaches to GenAI tools (Terry), and teachers are creating lesson plans around these tools (e.g., Exploring AI pedagogy; Gardner). The WAC Clearinghouse published Teaching with Text Generation Technology, which contains chapters on using GenAI to identify bias and raise ethical concerns, as well as using the technology as an integral part of the writing process.

Still, there is much we don’t know. We need to understand what others are doing and how they are working with GenAI. We need to know more about students’ experiences and perspectives. We could also use this information not just to adjust, but to take the lead in using GenAI writing tools. Who better to navigate the problems and promote the benefits than writing centers?

Methodology

This study consists of three major components: (1) a survey of clients, (2) a survey of writing center administrators, and (3) interviews with clients.

For the first component, in May 2023 an IRB-approved survey (see Appendix A) was sent to everyone (e.g., students, alumni, faculty) on ELSO’s listserv and to the clients of ELSO’s Writing & Presenting Tutoring Service, and 51 responded. The survey was updated and sent out again in 2024 (see Appendix B) and 42 responded.

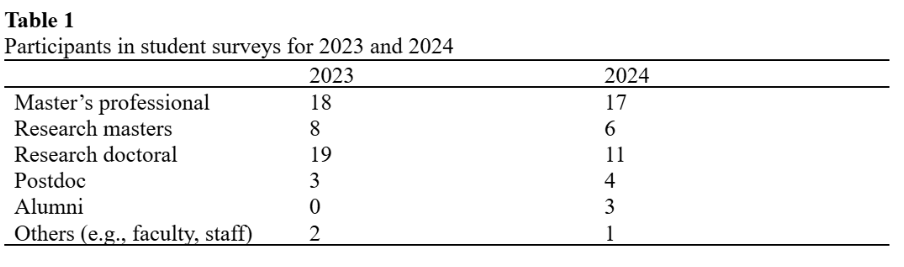

For the second component, in August 2023, an IRB-approved survey of about 25 questions (see Appendix C) was shared with writing center administrators and interested parties (e.g., faculty, tutors) via listservs and the Writing Center Administrator’s Facebook page. The same survey was updated (see Appendix D) and sent out again in August 2024. Preliminary results were released in two reports (Lindberg et al.; Lindberg and Domingues). In 2023, there were 66 participants, and in 2024 there were 81. Most participants were affiliated with writing centers that worked primarily with undergraduate students. Participants primarily identified as writing center administrators, but there were also tutors, faculty, and staff. A breakdown of participants is shown in Table 1.

For the third component, the survey of clients included an interview request. Twelve clients accepted, and 11 were interviewed in May and June of 2023 (see Appendix E). In December 2023, seven participated in follow-up interviews (see Appendix F). In total, nine of those interviewed were international graduate and professional students, one was a postdoc, and one was a visiting scholar. All interviewees came from abroad and use English as an additional language. Interviews were conducted over Zoom and lasted from about 30 minutes to just over an hour. According to the IRB protocol, all participants’ identities are protected, thus pseudonyms are used in this article.

To create themes from interview data, I followed Charmaz’s advice on memo writing. Before and after interviews, I kept notes, listing possible themes. Later, in a reiterative process, I transcribed interviews, revisited themes, and made adjustments, until I came up with the themes presented below.

I should note the limits of the study. Survey takers were anonymous and it is impossible to tell how many took the survey both years. Thus comparison can only be made generally. Quantitative data are drawn from small sample sizes, which did not warrant statistical analyses, thus, again, only general conclusions can be drawn. However, both the qualitative and quantitative data tell a consistent story, one that is reasonable and, arguably, expected, so I believe comparisons are valid.

A note on the figures given below: percentages are provided so tables will accurately portray comparisons between the two years, but the total number of those who answered questions is given in parentheses. In some cases, percentages may not add up to 100 because they were rounded to the nearest tenth.

Finally, in this article, the term GenAI writing tool is used. The actual wording on the survey in 2023 was AI chatbot and in 2024 GenAI tool. In each case, ChatGPT was consulted and asked which term it advised using. Each year it had a different suggestion. GenAI is used in this paper based on a recommendation of a human (and a friend), Jane Freeman, Director of the Graduate Centre for Academic Communication, University of Toronto.

Results

In this section, the results from the 2023 and 2024 studies are presented. The data from both years support a common narrative: The initial impact of GenAI writing tools waned, and now all parties are becoming more focused on what to do with these tools.

Results from Surveys of Writing Center Administrators and Interested Parties

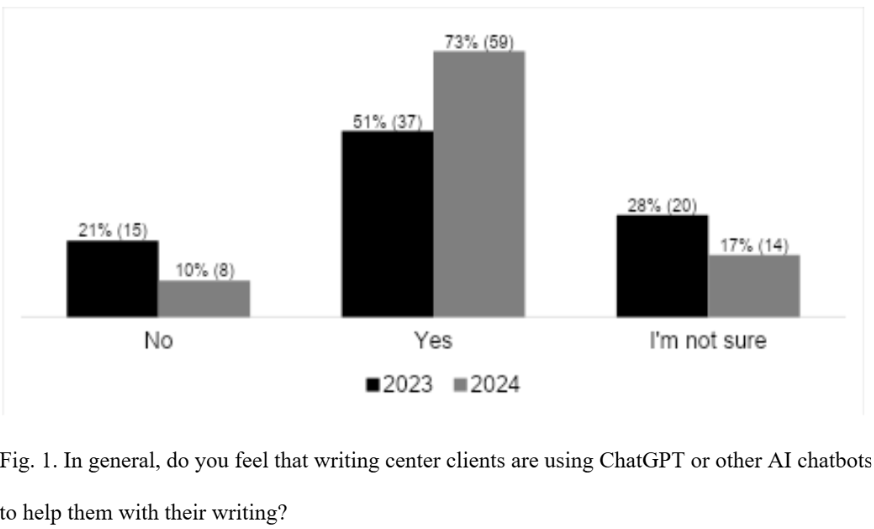

In 2023 and 2024, writing center administrators and interested parties were asked if they felt students were using GenAI writing tools. Fig. 1 illustrates a shift from no to yes.

Participants were asked how they felt about the impact of GenAI writing tools on their centers. As seen in Fig. 2, attitudes were skewed negatively, but from the first survey to the second, there was a substantial drop in “a little negative” and an increase in “neutral” and positive feelings, indicating that attitudes were becoming at least not as negative.

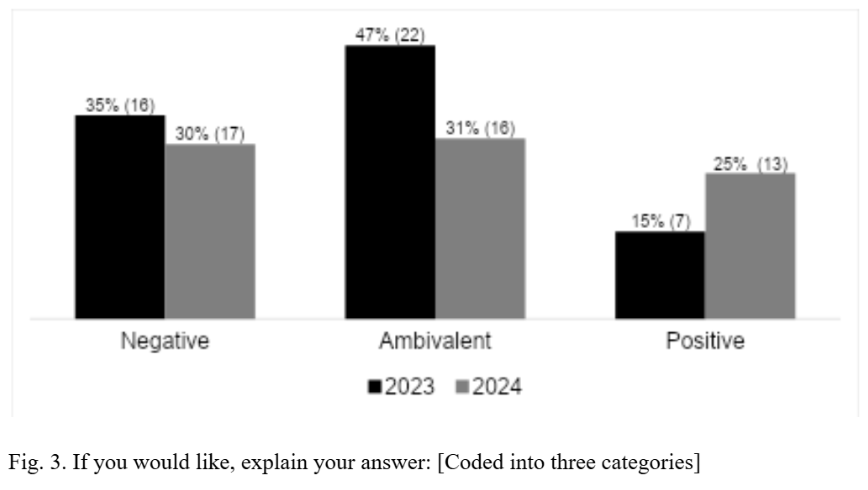

Participants were given the opportunity to explain their feelings about the impact of GenAI writing tools. With only a few exceptions, responses can generally be divided into three main categories: (a) negative, (b) positive, and (c) ambivalent. From 2023 to 2024, there was a shift from negative and ambivalent to positive, as Fig. 3 shows.

The most notable difference is 16% more ambivalence in 2023. One 2023 participant stated, “I think AI tools have tremendous potential to positively influence the quality of client writing, which is excellent. I believe this positive influence will result in significantly fewer clients needing assistance in the writing center, thus having a negative impact on the writing center itself.” This weighing of both sides decreased in 2024, implying that more administrators and interested parties had made up their minds about GenAI writing tools. In fact, some participants were embracing the new technology, with one stating, “I think AI is a very powerful tool and could prove extremely useful. We just have to figure out how to implement it correctly.”

Another notable difference between the two years is that in 2023, three participants complained that the technology had been thrust upon them without their consent. One participant noted, “It makes me angry that tech corporations in general have so much influence over our lives.” This sentiment was absent in 2024, implying that participants had become more resigned to the technology.

There was also a shift away from the negative impacts on writing center usage. In 2023, six participants expressed concern that the writing center’s occupancy would decline because students would turn to GenAI writing tools. One participant claimed, “I don’t think that there will be much work for writing center tutors or writing centers in general in the next 10 to 20 years.” In 2024, this concern was only given by four participants, while two others explicitly stated GenAI writing tolls had not impacted their occupancy levels, and another two were not sure.

Not surprisingly, in 2023 when GenAI tools were still new, participants did not report students bringing in GenAI-generated text. In fact, one participant stated bluntly, “I haven’t seen any student papers that are GenAI-generated come into the WC.” However, in 2024, GenAI tools had become more widespread, and six participants directly referred to GenAI-generated texts showing up in sessions, with one stating,

I personally have had many appointments where the writer was using ChatGPT (and either admitted it, or it was obvious through language use/professor feedback). I usually end up working with these students to rewrite AI sentences so that it’s instead in their own words and try to emphasize the importance of their voice in their writing.

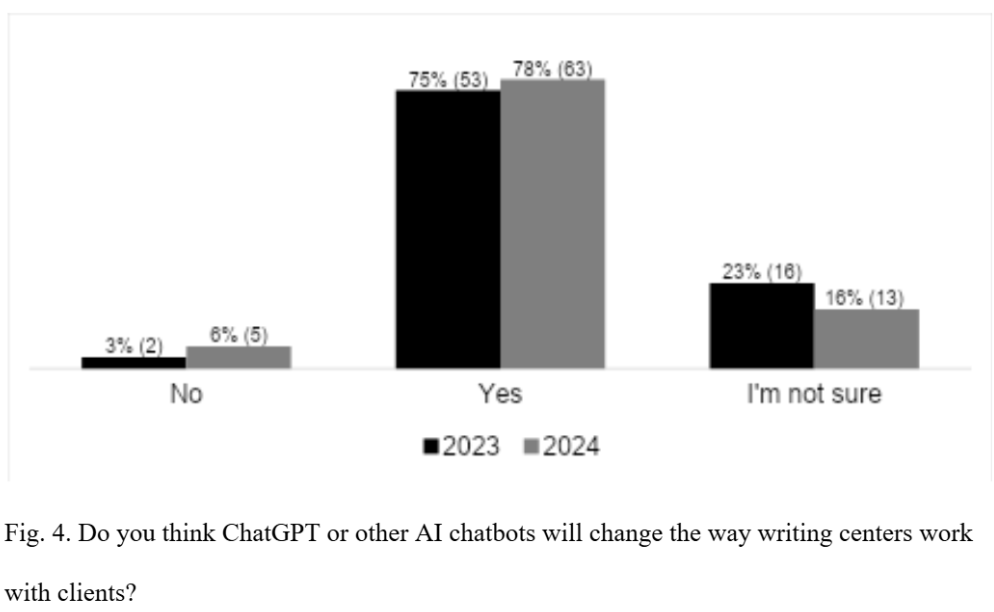

Participants were asked if they thought GenAI writing tools would change the way writing centers work with clients. In both years, the vast majority felt they would (Fig. 4).

Sixty participants elaborated their answer. Twenty-eight felt that writing centers will need to work with AI writing tools, ten mentioning that tutors will need to be able to use them with clients. One stated, “Writing center consultants will need to become conversant in generative AI usage strategies and how they affect clients' research and composition processes.”

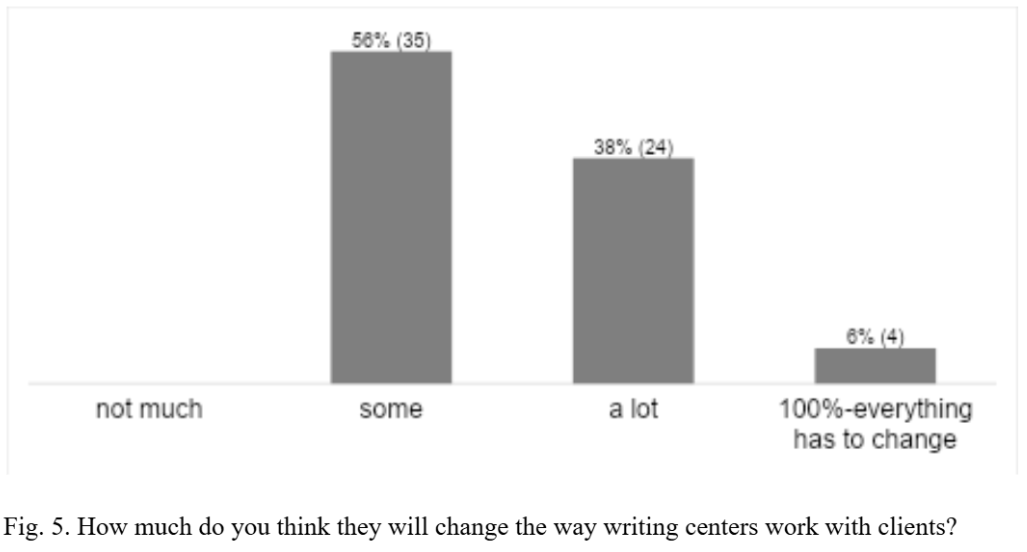

In only the 2024 survey were participants asked how much they thought this change would be. The majority felt it would only be “some” (Fig. 5).

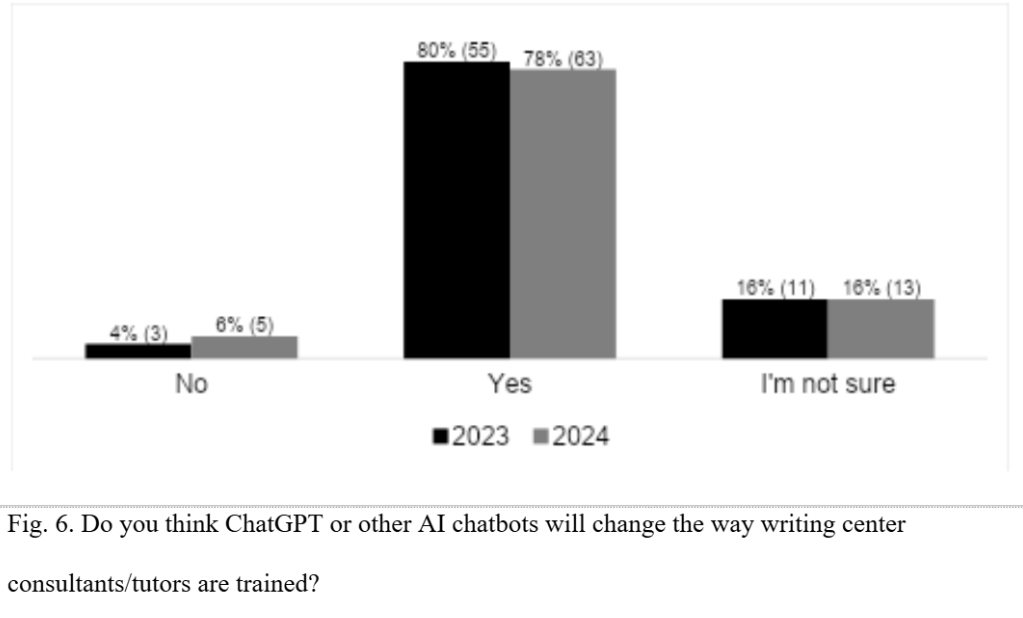

Participants were asked if they thought GenAI writing tools will change the way tutors are trained. The results are very similar in both years, with the vast majority feeling they would (Fig. 6).

When asked how substantial this change would be, there is a shift from “some” to “a lot” (Fig. 7).

Participants were asked how tutor training would change. In 2023, 54% of the 46 participants who answered the question felt that tutors would need to become familiar with GenAI writing tools, so they could incorporate them into sessions. This was roughly the same in 2024 for the 66 respondents, 58% of whom felt they would.

Participants also felt tutors would need to be able to recognize GenAI-produced texts and discuss possible problems, such as plagiarism, but there was a significant drop from 50% in 2023 to 27% in 2024. The decrease may be an indication that there was less concern that students were going to have GenAI write their papers and more concern that writing centers would need to learn how to work with these tools.

Finally, participants were asked if they personally used GenAI writing tools. Most did but not substantially. However, from 2023 to 2024, Fig. 8 indicates a shift toward more usage.

There was also a shift in what participants were using the tools for. In 2023, 40% (n=15) respondents reported experimenting with them, sometimes to see what students were doing. However, in 2024, only 18% (n=11) mentioned experimenting with them. Perhaps experimenting was winding down. In addition, the percentage of participants using the tools for writing, including brainstorming and writing low-stakes texts (e.g., emails) was slightly more in 2023 (60%, n=23) than in 2024 (51%, n=31).

Conclusions of Surveys of Writing Center Administrators and Interested Parties

Based on the two surveys, evidence indicates that writing center administrators’ and interested parties’ attitudes and usages of GenAI writing tools shifted from 2023 to 2024. Participants were becoming accustomed to GenAI writing tools, showing less ambivalence toward them, accepting them in general, and feeling less trepidation that they would decrease enrollment. More writing center administrators and interested parties felt the new technology would impact the way writing centers work with clients and train tutors, and in 2024, GenAI-written papers were showing up in sessions. However, the majority of study participants were not using GenAI writing tools substantially, though a minority had fully embraced them.

A general pattern can be drawn: The shock of GenAI tools is wearing off and administrators and interested parties are seeing them as another tool that is useful and is becoming part of the writing center’s repertoire.

Survey of Students

In this section and the next, evidence indicates students appeared to have embraced GenAI writing tools quickly, but then their excitement waned, and students began to realize these tools are not a panacea for all writing issues but instead a powerful technology that has a lot of potential, but is only as good as the skills of those who wield it.

In the spring of 2023 and 2024, surveys were sent out to clients of the ELSO Writing & Presenting Tutoring Service. Like writing center administrators and interested parties, from 2023 to 2024, generally more students were using GenAI writing tools. In 2023, 75% (n=33) of students who took the survey had used one to help with their writing, whereas in 2024 this rate increased to 84% (n=21).

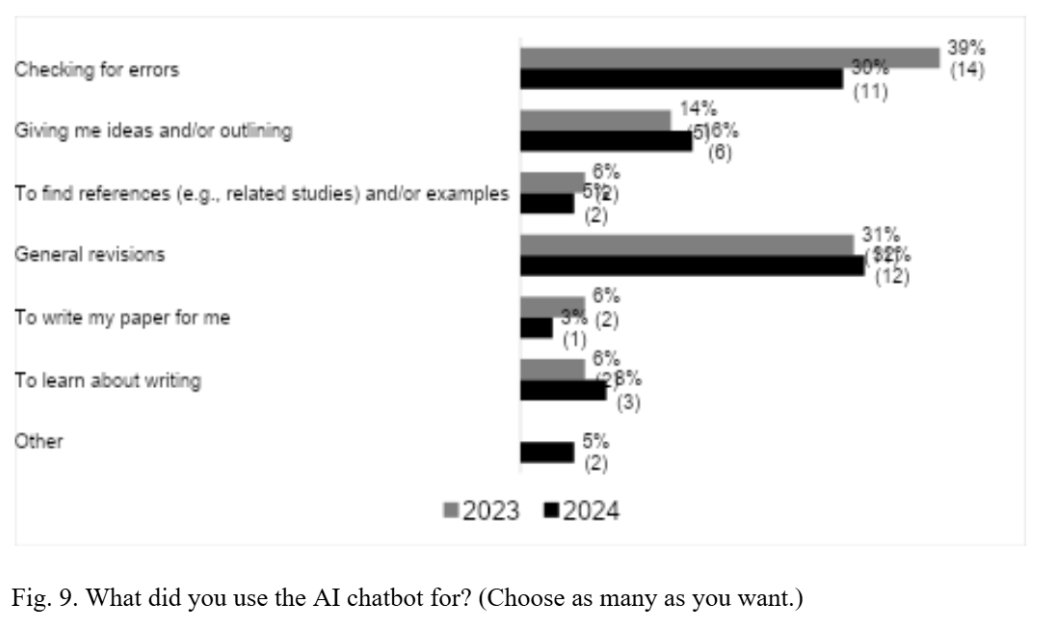

Students reported using them for a variety of purposes, most commonly checking for errors (Fig. 9), which could be an indication that EAL students were using GenAI writing tools to adjust their written accents. (See section My Context with EAL Students above.)

Participants were asked what types of projects they were using GenAI writing tools for. In both 2023 (n=10) and 2024 (n=7) the most common answer was research papers, followed by class assignments (n=3 in 2023; n=7 in 2024). Other uses included writing cover letters and resumes, rephrasing, and, as one student wrote, “anything, but not to generate writing.” In fact, having a GenAI writing tool write a paper for students was one of the least popular tasks selected.

Some scholars have touted GenAI tools as a substitute for tutoring (Mollick; Rahman and Watanobe). Survey results indicated that this was true. When asked if students had used a GenAI writing tool instead of seeing a tutor, about half had in 2023 and seven percent more had in 2024 (Fig. 10).

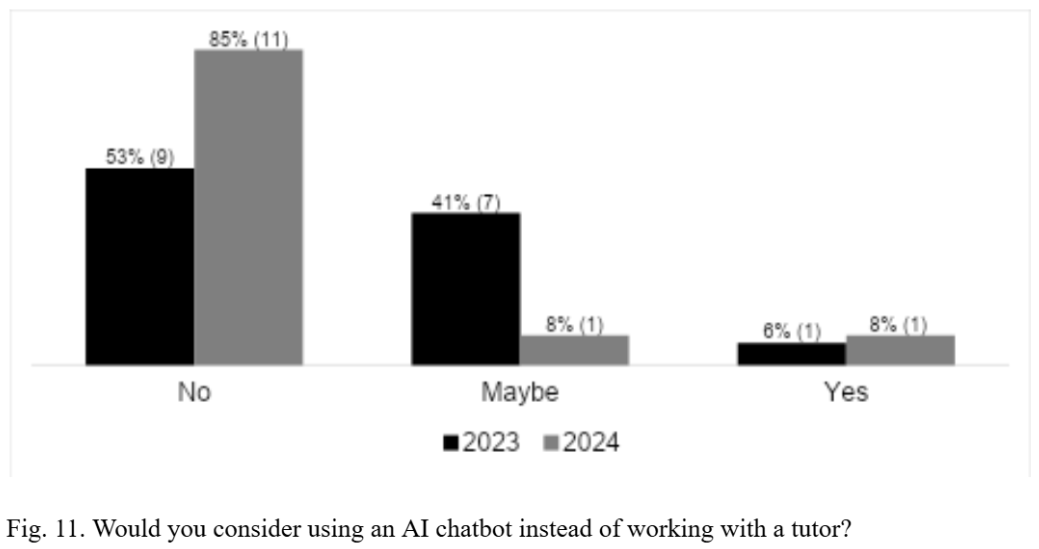

However, the results are complicated. When asked if they would consider using a GenAI writing tool instead of a tutor, from 2023 to 2024, there was a dramatic negative shift (Fig. 11).

When asked why students used GenAI writing tools instead of going to see a tutor, for both 2023 and 2024, the majority felt they are faster and more convenient than working with a tutor (Fig. 12). Interestingly, relatively few felt that GenAI writing tools are more effective than tutors.

One conclusion is that together, these two data sets indicate that the initial shine of GenAI dulled as students found the tools were not a substitute for human help.

Two survey questions concerned GenAI writing tools’ effectiveness. The first asked if students found GenAI writing tools’ assistance useful. In Fig. 13, the numbers are mostly the same for both years, except for a substantial decrease in the number who felt help was “extremely” useful.

This waning of enthusiasm also occurred when students were asked to evaluate GenAI writing tools’ results. From 2023 to 2024, a substantial number of students judged them more “so-so” and less “really great”. Together, these two data sets indicate that the luster of GenAI had dulled.

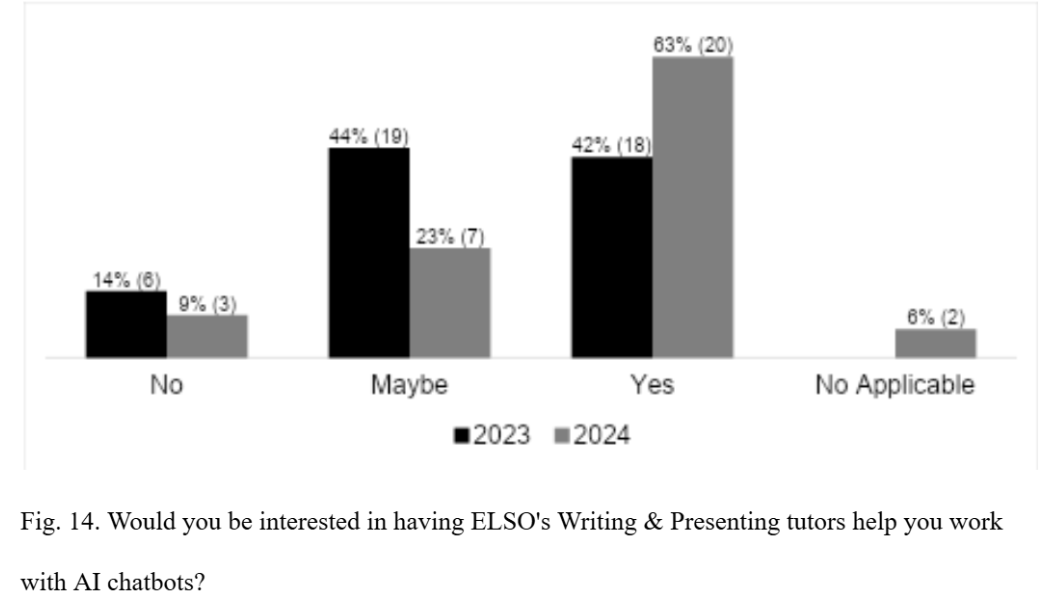

If students were becoming less smitten with GenAI writing tools, it stands to reason that they would seek help using them effectively. Indeed, from 2023 to 2024, a much higher percentage indicated that they would (Fig. 14).

Conclusion of Surveys of Students

Survey results indicate that more students are using GenAI writing tools for many purposes because these tools are so convenient. However, the initial excitement around GenAI seems to have faded. After a year, they found the tools less effective than human help and were less inclined to think of them as a substitute for a tutoring session.

Results from Interviews with Students

The 2023 survey of students included an invitation to be interviewed. Eleven students agreed and I spoke to them in May and June of the same year. Interviews were transcribed and analyzed to come up with the themes below. In general, the interview data support the narrative from the student surveys: The luster of GenAI writing tools faded, and some students had begun to return to tutoring.

Using ChatGPT as a Proxy for Tutoring

ChatGPT was the first GenAI chatbot to gain widespread usage, and the only chatbot used by students who were interviewed. Before ChatGPT, Jasper, an architecture master’s student, had been a regular tutoring client, attending 79 sessions from fall 2021 to fall 2022, often to adjust his written accent. However, in spring 2023—the semester after ChatGPT was introduced—he only attended three sessions. During our first interview, he was convinced that ChatGPT could take the place of tutoring. He claimed, “I think I use it every day and a lot every day for everything, for writing and for getting some brainstorm or some inspirations and to ask it to edit my writing and even use it to check words.” Jasper also used ChatGPT to write content. One strategy he used was to upload a page of his writing and ask ChatGPT to “remember” it. Then he would ask it to write a paragraph using his style. Jasper had become so reliant on ChatGPT that when asked if he could write without it, he replied, “To be honest, I think now I cannot.” Then he added, “I am already addicted to it.”

Something Jasper used ChatGPT specifically for was “cleaning up a draft,” which he described as choosing more appropriate vocabulary and phrasing, both of which are considered part of adjusting accented writing. This was true for other interviewees, all who use English as an additional language. Yasmine, a humanities doctoral student, noted that ChatGPT could “polish” her expressions, making her language more “professional” and “academic.” Trinity, a business master’s student, asked ChatGPT to “fix the wrong expressions,” changing them into “natural language expressions.” Tru, a social science doctoral student, asked ChatGPT to give alternative expressions to her words that seemed “weird.” Then she looked over the synonyms ChatGPT provided to find the appropriate ones. Elisa, a PhD student in information science, made this adjustment with the terse prompt “check grammar.” Then ChatGPT would rewrite her text. Afterwards, she would read through the text and determine if the revisions were acceptable.

While ELSO tutors could help adjust written accents, ChatGPT was more convenient. Jasper said making an appointment with a tutor took time and effort. However, using ChatGPT required very little investment. Kai, a postdoctoral researcher in agricultural and life sciences, voiced a similar sentiment, stating, “[ChatGPT] improved my productivity a lot now by reducing the time that I have to spend on editing some language issues.” He added, “[Addressing language issues] has become just a five-minute job.” Elisa admitted she often waited until the last minute to write her papers. At that point, it might be too late to make a tutoring appointment, and ChatGPT was a convenient alternative. Reese, a doctoral student in information science, said she didn’t have time to go to multiple tutoring sessions. Using ChatGPT was much more efficient.

Using GenAI writing tools gave Jasper confidence to progress further than he would have previously considered. Before ChatGPT, he had wanted to apply for a grant but did not feel his writing ability was good enough. However, with ChatGPT’s help, he applied and was awarded the grant. His success gave him confidence to pursue a PhD, and with ChatGPT’s help, he felt that he would be able to meet the writing requirements to earn a doctoral degree.

Problems with Gen AI Writing Tools

Despite the benefits of GenAI writing tools, there were certain needs that they could not fulfill, and there were new needs that they created. One problem with GenAI writing tools is the companies that host them lack clear privacy policies. Consequently, no participant felt confident that the text they uploaded would be kept private. Tru was concerned that when she submitted text, it would go into a database, and later she might be flagged for plagiarizing her own words. Conversely, Elisa was concerned that the text that ChatGPT generated might be plagiarized, and if she used it, her writing would be flagged. Ariana, an engineering doctoral student, had just been hired as an intern in a large tech company and was assigned to work on a patent. She was given specific instructions not to upload any part of the patent to a GenAI chatbot because the information would not be secure.

Some students took measures to ensure privacy. Ariana did not include names when she asked ChatGPT to write her an email. Tru never uploaded more than a paragraph at a time, reasoning that ChatGPT would not have her full paper. Elisa used ChatGPT to proofread her papers, but she would not use it if she was co-authoring because she felt it would violate her co-writers’ privacy.

However, some students admitted that trying to retain privacy was a losing battle. Reese said, “Everything I write online has been recorded by some software I use, and I don't trust their private policies, so everything I write has already been stolen by some evil big companies, so there's no difference if I put it in ChatGPT or not.” Yanis, an engineering master’s student, had similar feelings, stating, “I should be concerned. But I know right now since our information is already exposed to everything, I feel like there's nothing I can do.”

Along with privacy issues, there are ethical concerns (Yadava 218). Some students stated they had seen course syllabi, journal guidelines, and application stipulations that limited or banned the use of GenAI tools. However, none of the students were aware of any rules on the university or program level. The rules only seemed to come from individual professors, and even then they were not always followed. During my interview with Trinity, she initially thought that one course she was currently enrolled in allowed students to use GenAI writing tools to write papers. However, as we spoke, she became doubtful. She then shared screens and opened up her syllabus, so we could look it over. She was correct. However, there was a stipulation that if they did so, they were to include a description of how they used them. Trinity had not noticed the paragraph before, nor had she written such a description despite using ChatGPT to proofread her papers. She rationalized that she was just using it to check for mistakes—not generate ideas—so she did not feel she had violated the rule. Similarly, Elisa and Ariana felt that if they used ChatGPT to proofread, they were not doing anything unethical nor did they need to disclose the usage.

Lack of policy clarity left Jasper confused. In our follow-up interview, he was applying for a PhD program that stipulated GenAI writing tools should not be used when writing application material. He confessed, “I don’t know what does it mean by don’t use it—don’t use it to write your paper, but may I use it to adjust it?” Jasper rationalized that if other people can afford to hire an editor, he should be able to use ChatGPT similarly.

Ultimately, the ethics of using GenAI tools for writing are difficult, something students who were also teachers had to face. Both Reese and Tru were teaching assistants for undergraduate classes, and both courses forbade the use of GenAI writing tools to generate texts. Despite the rule, both Reese and Tru said that they had seen students’ papers that they thought were GenAI written. However, since there was no reliable way to test for GenAI-generated text, neither took action. Reese explained, “There was no way to verify, so we just dropped it.”

The lack of clear policies on GenAI writing tools can cause students to feel that any use may be deemed unethical, and, consequently, they may be reluctant to discuss the matter. None of the interviewees had openly discussed the ethical use of GenAI tools with their colleagues or professors. As a TA, Reese didn’t expect her students to admit they were using GenAI tools because doing so would be “taking a big risk” that the teacher might grade them negatively. However, none of the participants were overly concerned. Elisa admitted she felt a little guilty when she started to use ChatGPT but not as much anymore. “Like, yeah, it doesn’t matter,” she said. “We already know, like, everyone is using ChatGPT.”

Of the problems noted so far, all can be addressed through technological adjustments that could ensure privacy and also explicit policies that could clarify GenAI usage. However, Declan, a visiting scholar, brought up a more complicated problem. He was reluctant to use ChatGPT because he thought it would impede his learning process, and he really wanted to improve his English language abilities. At the end of our interview, though, he had become more curious and said he might try it.

Another more complicated problem emerged when students used ChatGPT to adjust their written accents. Its voice was not what they wanted. In our first interview, Reese described how she would give ChatGPT a bullet list of notes and have it write a paragraph for her. However, in our second interview, she said that she didn’t like the chatbot’s style, which she described as condescending, like an authority speaking to subordinates. When asked what made the chatbot’s voice patronizing, she said it used long sentences and words that are too formal. Consequently, she had to go through ChatGPT-generated text to change words, phrasing, and syntax in order to reinsert her voice. At the time of our follow-up interview, she had quit asking ChatGPT to write for her. She found it easier to compose without it.

In a follow-up interview, Jasper also said his opinion of ChatGPT had evolved. He still praised it and relied on it to adjust his written accent but questioned if it represented his voice. While applying for PhD programs, he had ChatGPT write up some of his application statements. “When I read it, I thought, it’s totally not me. It’s not acceptable.” This was a similar sentiment to those held by Tru, Trinity, and Elisa. Perhaps the strongest reaction against ChatGPT’s voice came from Yasmine, who felt it repeated things too often and speaks “like a robot.”

Problems with voice, privacy, and ethics are issues of concern, but for some participants, the biggest problem with ChatGPT was that the allure had worn off and they had become disappointed with the results. During our follow-up interview, Reese said she rarely used ChatGPT anymore. She felt her language and writing abilities had improved enough that cutting and pasting into ChatGPT had become too slow and cumbersome. Ariana was also disappointed with ChatGPT. She had tried to use it to change her tone (e.g., from informal to formal) but found the results lacking, so she started using it less. Yanis asked ChatGPT to help him with structure and transitions but found it unhelpful. Yasmine said that when she tried to delve deeper into a subject (e.g., “What is formal language?”), ChatGPT would inevitably end up giving her repetitive answers and circular logic (e.g., “Formal language is not slang”—“Slang is not formal language”).

For some students, after the luster wore off, they found only limited usage for ChatGPT. The first time I interviewed Tru, she said, “When you first use [ChatGPT] you feel very fascinated about it, like how powerful and how convenient the tool is.” However, after five months of usage, she saw it as just another tool. In fact, in our follow-up interview, she preferred an app called QuillBot for paraphrasing and another called Grammarly for proofreading because both could be used in-text and did not require the cutting and pasting that was needed for ChatGPT. She used Google Translate because she felt it was more accurate. Occasionally, she still used ChatGPT for written accent adjustment, but it had become just another tool among many.

Returning to Humans

Some participants had actually started returning to human tutoring. As noted, Jasper had been a regular tutoring client, but when he discovered ChatGPT, he almost stopped attending sessions. However, in the fall of 2023, he attended 30 sessions, including nine that were face-to-face. It should be noted that during that semester, only one tutor offered face-to-face sessions, so attending nine sessions took a concerted effort. Though Jasper still valued ChatGPT, he felt that tutors provided better feedback—even on surface-level matters and particularly with structure. He felt ChatGPT would never be good at giving feedback on structure because such analysis requires creativity, which the chatbot does not have. Ultimately, he felt that “If I want to make my writing even better, then I have to work with tutors.”

In our second interview, Tru also wanted human feedback, stating, “At the end of the day, I’m still writing for a human rather than an AI reader.” She added, “I still need my paper to be read by a human rather than a robot.” In our follow-up interview, Trinity expressed similar sentiments, stating that she might use ChatGPT to help her write papers, but she wanted her final version to be checked by a human.

Interestingly, at the beginning of this section, it was noted that students appreciated the convenience of ChatGPT, but conversely, some valued the investment it took to see a tutor. Jasper noted that if he made a tutoring appointment, knowing a human would be reviewing his writing motivated him to write better. Ariana felt similarly.

The students’ attitudes towards ChatGPT from our first interview to our second shifted, none more so than Jasper, who had once claimed to be addicted to the chatbot. He went from using ChatGPT for everything to becoming disenchanted with its voice and general feedback. He had returned to tutoring, but he still used ChatGPT to check his language. For Jasper and others, ChatGPT had become a tool that had its uses, such as adjusting accented language.

Discussion and Conclusions

This article starts with Graham Stowe’s 2023 blog post, in which he argued that we needed more research to know how to respond to GenAI writing tools. This article presents such research and constructs a narrative based on it.

The narrative has two sides. For writing center administrators and interested parties, the shock of GenAI had waned. They became less negative about its impacts and accepted it in a variety of ways. For students, nearly the opposite was true. Some were early adopters, seeing it as a panacea for addressing writing problems and a proxy for tutoring sessions. But they learned that GenAI writing tools also come with problems and ultimately are just limited tools. Some were looking back to tutoring for assistance to work these tools effectively and also to receive human help. The two sides can be seen as meeting, realizing GenAI writing tools are neither the inevitable demise of writing centers nor a cure-all, but instruments that can be useful.

For valid reasons, some administrators are still primarily suspicious and resistant to the new technology, but students appear to be using it more, even knowing its limitations. Now, writing centers are seeing GenAI-created texts, and there appears to be no way to stop or pause the technology. Consequently, some administrators have already started incorporating GenAI writing tools into their training.

There are many reasons that writing centers are well suited to work with GenAI writing tools and even to benefit from them. These tools can relieve writing centers from being proofreading services. Even EAL students seeking written accent adjustment are no longer as prevalent. Instead, we can focus on higher-level concerns, such as working with broad structures.

In addition, we have features that computers can never match. We provide human help. Only we can give human reaction, while we continue to offer safe spaces, building community and making students feel like they are part of the institutions we work for.

We can also address problems that have emerged. We are in a unique position between faculty and students. We can assist students to navigate policies, and we can provide input to create new policies that are fair to both sides. We could take the time to investigate privacy issues to help students safeguard their work. With writing studies knowledge, we can ensure students avoid pitfalls, such as losing their agency and voice. We have the time and expertise to develop strategies for using GenAI writing tools to work effectively and ethically while still learning.

However, as GenAI writing tools become mainstream, we should not just accept and work with them. We have the opportunity to take the lead and pioneer them. With our knowledge and experience, we can develop strategies and prompts that are difficult or even impossible to create without the technology.

The potential is intriguing. These tools can quickly show the boundaries of a genre (e.g., structure, style, tone), giving students an indication of what is accepted and what is not. In seconds, they can find the central point of a paper and show how that point is (or is not) developed and supported. They can map how a writer guides or does not guide readers and assess the effectiveness of the guidance. GenAI has the potential to change the way we write, and writing centers have the experience and position to pioneer these techniques. (For specific strategies, see Lindberg.)

However, there are several problems (aren’t there always?). The first is that many of us in administration are experienced scholars and writers and we don’t need GenAI writing tools. Thus, we don’t use them. This study shows that this isn’t always the case—in fact, some of us are already legitimate GenAI pioneers. But for others (initially including myself), it just seems like another annoying technology, and we search for reasons not to engage with it. I’ve been in multiple conversations that turn into gripe sessions about how bad GenAI writing tools are, such as that they support the dominant language and cause more class division. These are real problems and need to be addressed, but they don’t distract from the fact that these writing tools are the most powerful ones ever created. Ultimately, we need to engage with them. Not doing so would be woefully neglectful.

Unfortunately, there is another larger problem: writing with GenAI is difficult (Lindberg, “Writing with GenAI Is Difficult”). Though these tools have been touted as quick, easy ways to write papers, this only applies to very low-stakes writing. If writing is high-stakes, public facing, and part of a repertoire that creates that author’s reputation, using GenAI writing tools is complicated. Chatbots such as ChatGPT and Copilot need to be trained—they might not even know what a paragraph or sentence is. A user may need to go back and forth with them to get the results they want, creating prompts that require an advanced level of metacognitive thinking. After all, a tool is only as good as the skills of the user.

If we want to pioneer GenAI writing tools, we are going to have to work for it. We will need to publish more articles on strategies and approaches to working with GenAI writing tools. At conferences, we need workshops where strategies are taught and round tables where they are debated. Something that is becoming evident is that the technology is not going to go away or even pause. Future generations are going to use them as an integral part of their writing process. We will need to convince them that writing centers are still relevant and worth using.

Together, we have a much better chance of guiding the use of this new technology in a way that is ethical, effective, and ensures students continue to learn, and we can continue not just to exist but to thrive.

Works Cited

Ali, Mohammad Javed and Swati Singh. “ChatGPT and Scientific Abstract Writing: Pitfalls and Caution.” Graefe’s Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology, 25, May 2023, pp. 3205-3206, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00417-023-06123-z.

Bryan, Mathew D. “Bringing AI to the Center: What Historical Writing Center Software Discourse Can Teach Us About Responses to Artificial Intelligence-Based Writing Tools.” The Proceedings of the Annual Computers and Writing Conference, 2023, edited by Christopher D. M. Andrews, Chen Chen, and Brandy Dieterle, The WAC Clearinghouse, 2024, pp. 15-26, https://doi.org/10.37514/PCW-B.2024.2296.

Byrd, Antonio. “Truth-Telling: Critical Inquiries on LLMs and the Corpus Texts That Train Them.” Composition Studies, vol. 51, no. 1, 2023, pp. 135-142.

Cox, Michelle. “In Response to Today’s ‘Felt ‘Need’: WAC, Faculty Development, and Second Language Writers.” WAC and Second Language Writers: Research Towards Linguistically and Culturally Inclusive Programs and Practices, edited by Terry M. Zawacki and Michelle Cox, The WAC Clearinghouse, 2014, pp. 299-326.

Charmaz, Kathy. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide Through Qualitative Analysis. Sage Publications, 2006.

Graham, Scott. “Post-Process but Not Post-Writing: Large Language Models and a Future for Composition Pedagogy.” Composition Studies, vol. 51, no. 1, 2023, pp. 162-168.

Heaven, Will Douglas. “The Education of ChatGPT.” MIT Technology Review, vol. 126, no. 3, 2023, pp. 42-47.

Hotson, Brian. “GenAI and the Writing Process: Guiding Student Writers in a GenAI World (Part 1 of 2).” CWCR/RCCR Blog, 30 Aug. 2023, https://cwcaaccr.com/2023/08/30/productive-and-ethical-guiding-student-writers-in-a-genai-world-part-1-of-2/. Accessed 20 May, 2024.

Hotson, Brian. “GenAI and the Writing Process: Guiding Student Writers in a GenAI World (Part 2 of 2).” CWCR/RCCR Blog, Oct. 2023, https://cwcaaccr.com/2023/10/05/genai-and-the-writing-process-guiding-student-writers-in-a-genai-world-part-2-of-2/. Accessed 20 May, 2024.

Lindberg, Nathan. "We Should Promote GenAI Writing Tools for Linguistic Equity," Writing Center Journal: Vol. 43, no. 1, 2025 article 7, https://doi.org/10.7771/2832-9414.2078

Lindberg, Nathan. “Writing with GenAI Is Difficult” 16 December 2024. Strategies for Writing with AI. Substack, n.d. Accessed 11 Nov. 2024. https://substack.com/home/post/p-153231662

Lindberg, Nathan. Strategies for Writing with AI. Substack, n.d. Accessed 11 Nov. 2024. https://substack.com/@natelindberg?utm_source=user-menu.

Lindberg, Nathan and Domingues, Amanda. 2024 Report on Chatbots’ Impact on Writing Centers. ResearchGate, 2024. Accessed 11 Nov. 2024. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/383365521_2024_Report_on_AI_Writing_Tools'_Impacts_on_Writing_Centers.

Lindberg, Nathan; Domingues, Amanada, Zweers, Thari, and Goktas, Selin. Report on Chatbots’ Impact on Writing Centers. ResearchGate, 2023. Accessed 23 Aug. 2024. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/380264917_Report_on_AI_Chatbots'_Impact_on_Writing_Centers.

Madianou, Mirca. “Nonhuman Humanitarianism: When ‘AI for Good’ Can Be Harmful.” Information Communication and Society, vol. 24, no. 6, 2021, pp. 850–868, https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2021.1909100.

Mollick, Ethan. “Assigning AI: Seven Ways of Using AI in Class.” One Useful Thing, 12 June 2022, https://www.oneusefulthing.org/p/assigning-ai-seven-ways-of-using. Accessed 20 May, 2024.

Rahman, Mostafizer and Yutaka Watanobe. “ChatGPT for Education and Research: Opportunities, Threats, and Strategies.” Applied Sciences, vol. 13, no. 9, 2023, https://doi.org/10.3390/app13095783.

Shoufan, Abdulhadi. “Exploring Students' Perceptions of ChatGPT: Thematic Analysis and Follow-Up Survey.” IEEE Access, vol. 11, 2023, pp. 38805-38818.

Terry, Owens Kichizo. “I'm a Student. You Have No Idea How Much We're Using ChatGPT: No Professor or Software Could Ever Pick Up on It.” The Chronicle of Higher Education, 12 May, 2023.

Yadava, Om Prakash. “ChatGPT—A Foe or an Ally?” Indian Journal Thoracic Cardiovascular Surgery, vol. 39, 2023, pp. 217–221, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12055-023-01507-6.

Yan, Da. “Impact of ChatGPT on Learners in a L2 Writing Practicum: An Exploratory Investigation.” Education and Information Technologies, vol. 4, no. 1, 2023, pp. 13943-13967, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-023-11742-4.

Zawacki, Terry, et al. Valuing Written Accents: Non-Native Students Talk About Identity, Academic Writing, and Meeting Teachers’ Expectations. George Mason University Publication, 2007.

Appendices

Appendix A

ELSO spring 2023 Writing & Presenting Tutoring Survey

1. What college are you in or are/were affiliated with?

College of Agriculture and Life Sciences

College of Architecture, Art, and Planning

College of Arts and Sciences

Cornell SC Johnson College of Business

Cornell Ann S. Bowers College of Computing and Information Science

College of Engineering

College of Human Ecology )

School of Industrial and Labor Relations (ILR)

Cornell Jeb. E. Brooks School of Public Policy

Cornell Tech (New York City)

Cornell Law School

College of Veterinary Medicine

Weill Cornell Medicine (New York City)

School of Continuing Education

2. What graduate program are you in, or are/were affiliated with?

3. What is your position?

Professional student (master's or doctoral)

Research master’s research student

Research doctoral student

Postdoc

Alumni

Faculty, staff, or other

4. To help you with writing, have you used an AI chatbot (e.g., ChatGPT, Bard, YouChat)?

No

Yes

(If Yes, skip to 7. If No, go to 5 and 6. Then skip to 21.)

5. Why have you NOT used an AI chatbot?

I do not think they are useful.

No particular reason

I haven't yet, but I plan on using them at some point.

I don't know what an AI chatbot is.

Other __________________________________________________

6. Do you think you'll use an AI chatbot to help you with future writing?

No

I'm not sure, maybe.

Probably

Yes

Other __________________________________________________

7. Do you think you'll use an AI chatbot to help you with future writing?

No

I'm not sure, maybe.

Probably

Yes

Other __________________________________________________

8. To help you with writing, which AI Chatbot have you used (e.g., ChatGPT, Bard, YouChat)?

9. Which kinds or projects did you use them for (e.g., research paper, class assignment, grant proposal, job/PhD/fellowship application)?

10. Did you find the AI chatbot's help useful?

No

A little

Yes

Yes, extremely useful

11. Why not?

12. What was it useful for?

13. Did you find AI chatbots have any particular limitations (e.g., they are inaccurate, they changed my meaning)?

14. What limitation did you find (e.g., they are inaccurate, they changed my meaning)?

15. Have you used an AI chatbot instead of going to a tutor?

No

Yes

16. Would you consider using an AI chatbot instead of working with a tutor?

No

Maybe, I'm not sure.

Yes, I will at some point.

17. Why did you use an AI chatbot instead of going to the tutoring service? (Choose as many as you want.)

I wanted to try it and see if it worked.

It's faster and more convenient than working with a tutor.

It can help me with more matters than a tutor.

It does my work for me.

It offers more effective help than tutors.

Other _________________________________________________

18. What did you use the AI chatbot for? (Choose as many as you want.)

Checking for errors

Giving me ideas and/or outlining

To find references (e.g., related studies) and/or examples

General revisions

To write my paper for me

To learn about writing

Other __________________________________________________

19. How would you evaluate the results that you received from AI chatbots?

Bad

So-so

Good

Really great

Other __________________________________________________

20. If you want, explain your answer:

21. Will you use ELSO's Writing & Presenting Tutoring Service in the future?

No

Maybe

Yes, but not much

Definitely

22. Would you be interested in having ELSO's Writing & Presenting tutors help you work with AI chatbots?

No

Maybe

Yes

23. Could we contact you and ask you more about ELSO's Writing & Presenting Tutoring Service? If yes, please write your name and email address below.

Appendix B

ELSO spring 2024 Writing & Presenting Tutoring Survey

1. What college are you in or are/were affiliated with?

College of Agriculture and Life Sciences

College of Architecture, Art, and Planning

College of Arts and Sciences

Cornell SC Johnson College of Business

Cornell Ann S. Bowers College of Computing and Information Science

College of Engineering

College of Human Ecology )

School of Industrial and Labor Relations (ILR)

Cornell Jeb. E. Brooks School of Public Policy

Cornell Tech (New York City)

Cornell Law School

College of Veterinary Medicine

Weill Cornell Medicine (New York City)

School of Continuing Education

2. What graduate program are you in, or are/were affiliated with?

3. What is your position?

Professional student (master's or doctoral)

Research master’s research student

Research doctoral student

Postdoc

Alumni

Faculty, staff, or other

4. To help you with writing, have you used a Generative Artificial Intelligence (GAI) tool (e.g., ChatGPT, Claude, Copilot, Gemini)?

No

Yes

(If Yes, skip to 7. If No, go to 5 and 6. Then skip to 21.)

5. Why have you NOT used a GAI tool (e.g., ChatGPT, Claude, Copilot, Gemini)?

I do not think they are useful.

No particular reason

I haven't yet, but I plan on using them at some point.

I don't know what an AI chatbot is.

Other __________________________________________________

6. Do you think you'll use a use a GAI tool (e.g., ChatGPT, Claude, Copilot, Gemini) to help you with writing in the future?

No

I'm not sure, maybe.

Probably

Yes

Other __________________________________________________

7. Do you think you'll use a GAI tool (e.g., ChatGPT, Claude, Copilot, Gemini) to help you with writing in the future?

No

I'm not sure, maybe.

Probably

Yes

Other ) __________________________________________________

8. To help you with writing, which GAI tool have you used (e.g., ChatGPT 3.5, ChatGPT 4.0, Copilot, Claude, Gemini)?

9.Which kinds or projects did you use them for (e.g., research paper, class assignment, grant proposal, job/PhD/fellowship application)?

10. Did you find the GAI tool's (e.g., ChatGPT's, Claude's, Copilot's, Gemini's) help useful?

No

A little

Yes

Yes, extremely useful

11. Why not?

12. What was it useful for?

13. Did you find GAI tools (e.g., ChatGPT, Claude, Copilot, Gemini) have any particular limitations (e.g., they are inaccurate, they changed my meaning, the style is odd)?

No

Yes

14. What limitation did you find (e.g., they are inaccurate, they changed my meaning, the style is odd)?

15. Have you used a GAI tool (e.g., ChatGPT, Claude, Copilot, Gemini) instead of going to a tutor?

No

Yes

16. Would you consider using a GAI tool (e.g., ChatGPT, Claude, Copilot, Gemini) instead of working with a tutor?

No

Maybe, I'm not sure.

Yes, I will at some point. )

Not applicable because I'm no longer at Cornell.

17. Why did you use a GAI tool (e.g., ChatGPT, Claude, Copilot, Gemini) instead of going to the tutoring service? (Choose as many as you want.)

AI chatbot instead of going to the tutoring service? (Choose as many as you want.)

I wanted to try it and see if it worked.

It's faster and more convenient than working with a tutor.

It can help me with more matters than a tutor.

It does my work for me.

It offers more effective help than tutors.

Other _________________________________________________

18. What did you use the GAI tool (e.g., ChatGPT, Claude, Copilot, Gemini) for? (Choose as many as you want.)

Checking for errors

Giving me ideas and/or outlining

To find references (e.g., related studies) and/or examples

General revisions

To write my paper for me

To learn about writing

Other __________________________________________________

19. How would you evaluate the results that you received from a GAI tool (e.g., ChatGPT, Claude, Copilot, Gemini)?

Bad

So-so

Good

Really great

Other __________________________________________________

20. If you want, explain your answer:

21. Will you use ELSO's Writing & Presenting Tutoring Service in the future?

No

Maybe

Yes, but not much

Definitely

No applicable because I'm not longer at Cornell.

22. Would you be interested in having ELSO's Writing & Presenting tutors help you work with AI chatbots?

No

Maybe

Yes

No applicable because I'm not longer at Cornell.

23. Could we contact you and ask you more about ELSO's Writing & Presenting Tutoring Service? If yes, please write your name and email address below.

Appendix C

Survey of Writing Center Administrators 2023

What is your role with the writing center(s) at your institution?

Administrator (e.g., director, assistant director)

Consultant/tutor

Staff (e.g., office administrator)

party (e.g., faculty, someone working in a related area)

No relationship, but I know about it

No relationship, and I don't know much about it

Skip To: End of Survey If What is your role with the writing center(s) at your institution? = No relationship, and I don't know much about it

2. What is the name of the institution (e.g., college, university) that you are affiliated with?

3. For the writing center(s) at your institution, who are the primary clients?

Undergraduate students

Graduate and professional students

Postdocs

Faculty

Other __________________________________________________

I'm not sure

4. Who are the other (non-primary) clients? (Choose as many as apply.)

Undergraduate students

Graduate and professional students

Postdocs

Faculty

There are none.

Other __________________________________________________

I'm not sure

5. Generally, in the 2022-23 academic year, did the writing center at your institution see a decrease or increase in appointments made?

There was a decrease in the number of appointments made.

There was an increase in the number of appointments made.

The number of appointments was about the same.

I'm not sure.

Skip To: Q11 If Generally, in the 2022-23 academic year, did the writing center at your institution see a decrease... = There was an increase in the number of appointments made.

Skip To Q14 If Generally, in the 2022-23 academic year, did the writing center at your institution see a decrease... = The number of appointments was about the same.

Skip To Q14 If Generally, in the 2022-23 academic year, did the writing center at your institution see a decrease... = I'm not sure.

6. About how much of a general decrease?

Estimate 1% to 100% decrease _________________________

I'm not sure.

7. Do you feel the decrease was caused or partially caused by clients using ChatGPT or other AI chatbots instead of making writing center appointments?

No

Yes

I'm not sure.

Skip To: Q10 If Do you feel the decrease was caused or partially caused by clients using ChatGPT or other AI chat... = No

Skip To: Q10 If Do you feel the decrease was caused or partially caused by clients using ChatGPT or other AI chat... = I'm not sure.

Display This Question:

If Do you feel the decrease was caused or partially caused by clients using ChatGPT or other AI chat... = Yes

8. About how much of the decrease was caused by clients using ChatGPT or other AI chatbots instead of making writing center appointments?

Estimate 1% to 100% of the decrease _______________________________

I'm not sure.

Skip To: Q10 If About how much of the decrease was caused by clients using ChatGPT or other AI chatbots instead of... = I'm not sure.

9. What do you base your estimation for the decrease on?

10. What other factors might have caused the decrease?

Skip To Q14 If What other factors might ha... Is Empty.

Skip To Q14 If What other factors might ha... Is Displayed. Skip To: End of Block.

11. About how much of a general increase?

Estimate 1% to 100%+ increase (1) ____________________________________

I'm not sure (2)

Display This Question:

If About how much of a general increase? = Estimate 1% to 100%+ increase

12. What do you base your estimation for the increase on?

13. What do you think caused the increase?

14. In general, do you feel that writing center clients are using ChatGPT or other AI chatbots to help them with their writing?

No

Yes

I'm not sure.

Skip To: Q18 If In general, do you feel that writing center clients are using ChatGPT or other AI chatbots to help... = No

Skip To: Q18 If In general, do you feel that writing center clients are using ChatGPT or other AI chatbots to help... = I'm not sure.

15. What do you think clients are using them for? (Choose as many as apply.)

Proofreading (e.g., checking for “mistakes")

Adjusting for second language issues (e.g., non-native phrasing/vocabulary, non-native syntax)

Adjusting “tone” or “style” (e.g., formal/informal, academic/general audience)

Ideas (e.g., brainstorming topics, outlining, draft text)

Writing content for low-stakes texts (e.g., emails, minor class assignments)

Writing content for high-stakes texts (e.g., major class assignments, job applications, research articles, grant proposals)

Reading (i.e., summarizing/explaining texts)

Other __________________________________________________

I'm not sure.

Skip To: Q18 If What do you think clients are using them for? (Choose as many as apply.) = I'm not sure.

16. What do you think clients are using them for? (Choose as many as apply.)

Proofreading (e.g., checking for “mistakes")

Adjusting for second language issues (e.g., non-native phrasing/vocabulary, non-native syntax)

Adjusting “tone” or “style” (e.g., formal/informal, academic/general audience)

Ideas (e.g., brainstorming topics, outlining, draft text)

Writing content for low-stakes texts (e.g., emails, minor class assignments)

Writing content for high-stakes texts (e.g., major class assignments, job applications, research articles, grant proposals)

Reading (i.e., summarizing/explaining texts)

Other __________________________________________________

I'm not sure.

17. What do you base your selection(s) on (e.g., anecdotal evidence, survey, individual student's input)?

18. Do you think ChatGPT or other AI chatbots will change the way writing centers work with clients?

No

Yes

I’m not sure

Skip To: Q20 If Do you think ChatGPT or other AI chatbots will change the way writing centers work with clients? = No

Skip To: Q20 If Do you think ChatGPT or other AI chatbots will change the way writing centers work with clients? = I'm not sure.

19. How will they change the way writing centers work with clients?

20. Do you think ChatGPT or other AI chatbots will change the way writing center consultants/tutors are trained?

No

Yes

I’m not sure.

Skip To: Q23 If Do you think ChatGPT or other AI chatbots will change the way writing center consultants/tutors a... = No

Skip To: Q23 If Do you think ChatGPT or other AI chatbots will change the way writing center consultants/tutors a... = I'm not sure.

21. How much do you think it will change the way consultants/tutors are trained?

Not much

Some

A lot

100%--everything has to change

22. What specific ways will it change how consultants/tutors are trained?

23. Generally, how do you feel about the impact of ChatGPT and other AI chatbots on writing centers?

Very negative

A little negative

Neutral

A little positive

Very positive

There is no impact

24. If you would like, explain your answer:

25. Does the institution you are affiliated with have any policy/policies about using AI chatbots?

No

No, but (a) university-wide policy is/policies are being developed.

Yes, but only for parts (e.g., programs, individual professors)-not university-wide

Yes, university-wide

I'm not sure

Other __________________________________________________

Skip To: Q26 If Does the institution you are affiliated with have any policy/policies about using AI chatbots? = No

Skip To: Q26 If Does the institution you are affiliated with have any policy/policies about using AI chatbots? = I'm not sure

25. Please, describe the policies and who developed/is developing them:

26. At the institution that you are affiliated with, is there support (e.g., workshops, handouts, lists of resources) for using ChatGPT or other AI chatbots?

No

No, but support is being developed.

I'm not sure.

Skip To: Q28 If At the institution that you are affiliated with, is there support (e.g., workshops, handouts, lists... = No

Skip To: Q28 If At the institution that you are affiliated with, is there support (e.g., workshops, handouts, lists... = I'm not sure.

27. Please, describe the support and who developed/is developing it:

28. Do you personally use ChatGPT or other AI chatbots?

No

Yes, a little

Yes, sometimes

Yes, a lot

Skip To: Q30 If Do you personally use ChatGPT or other AI chatbots? = No

29. Which one(s) do you use, and what do you use it/them for?

Display This Question:

If Do you personally use ChatGPT or other AI chatbots? = No

30. Why not?

31. If there is anything else you would like to add, please, write it in the field below:

Appendix D

Survey of Writing Center Administrators 2024

What is your role with the writing center(s) at your institution?

Administrator (e.g., director, assistant director)

Consultant/tutor

Staff (e.g., office administrator)

party (e.g., faculty, someone working in a related area)

No relationship, but I know about it

No relationship, and I don't know much about it

Skip To: End of Survey If What is your role with the writing center(s) at your institution? = No relationship, and I don't know much about it

2. What is the name of the institution (e.g., college, university) that you are affiliated with?

3. For the writing center(s) at your institution, who are the primary clients?

Undergraduate students

Graduate and professional students

Postdocs

Faculty

Other __________________________________________________

I'm not sure

4. Who are the other (non-primary) clients? (Choose as many as apply.)

Undergraduate students

Graduate and professional students

Postdocs

Faculty

There are none.

Other __________________________________________________

I'm not sure

5. Is your service mandatory for clients?

Yes

No

Mandatory for some; optional for others

I don’t know

6. Generally, in the 2022-23 academic year, did the writing center at your institution see a decrease or increase in appointments made?

There was a decrease in the number of appointments made.

There was an increase in the number of appointments made.

The number of appointments was about the same.

I'm not sure.

Skip To: Q14 If Generally, in the 2022-23 academic year, did the writing center at your institution see a decrease... = There was an increase in the number of appointments made.

Skip To Q17 If Generally, in the 2022-23 academic year, did the writing center at your institution see a decrease... = The number of appointments was about the same.

Skip To Q17 If Generally, in the 2022-23 academic year, did the writing center at your institution see a decrease... = I'm not sure.

7. About how much of a general decrease?

A little (1-30)

Some 31-49%)

A lot (51-80%)

Severely (81-100%)

8. When did the decrease primarily occur? (Select as many as apply.)

Fall 2022

Spring 2023

Fall 2023

Spring 2024

I’m not sure

9. If you want, please comment on ChatGPT and/or other GAI tools (e.g., Copilot, Gemini, Claude) affecting your service.

10. Do you feel the decrease was caused or partially caused by clients using GAI tools (e.g., ChatGPT, Copilot, Gemini, Claude) instead of making writing center appointments?

No

Yes

I'm not sure.

Skip To: Q17 If Do you feel the decrease was caused or partially caused by clients using GAI tools (e.g., ChatGPT, Copilot, Gemini, Claude)... = No

Skip To: Q19 If Do you feel the decrease was caused or partially caused by clients using GAI tools (e.g., ChatGPT, Copilot, Gemini, Claude)... = I'm not sure.

Display This Question If Do you feel the decrease was caused or partially caused by clients using GAI tools (e.g., ChatGPT, Copilot, Gemini, Claude)... = Yes

11. About how much of the decrease was caused by clients using GAI tools (e.g., ChatGPT, Copilot, Gemini, Claude) instead of making writing center appointments?

Estimate 1% to 100% of the decrease _______________________________

I'm not sure.

Skip To: Q13 If About how much of the decrease was caused by clients using GAI tools (e.g., ChatGPT, Copilot, Gemini, Claude)s instead of... = I'm not sure.

12. What do you base your estimation for the decrease on?

13. What other factors might have caused the decrease?

Skip To Q17 If What other factors might have... Is Empty.

Skip To Q17 If What other factors might have... Is Displayed. Skip To: End of Block.

14. About how much of a general increase?

Estimate 1% to 100%+ increase (1) ____________________________________

I'm not sure (2)

Display This Question If About how much of a general increase? = Estimate 1% to 100%+ increase

15. What do you base your estimation for the increase on?

16. What do you think caused the increase?

17. In general, do you feel that writing center clients are using GAI tools (e.g., ChatGPT, Copilot, Gemini, Claude) to help them with their writing?

No

Yes

I'm not sure.

Skip To: Q20 If In general, do you feel that writing center clients are GAI tools (e.g., ChatGPT, Copilot, Gemini, Claude) to help... = No

Skip To: Q20 If In general, do you feel that writing center clients are GAI tools (e.g., ChatGPT, Copilot, Gemini, Claude)to help... = I'm not sure.

18. What do you think clients are using them for? (Choose as many as apply.)

Proofreading (e.g., checking for “mistakes")

Adjusting for second language issues (e.g., non-native phrasing/vocabulary, non-native syntax)

Adjusting “tone” or “style” (e.g., formal/informal, academic/general audience)

Ideas (e.g., brainstorming topics, outlining, draft text)

Writing content for low-stakes texts (e.g., emails, minor class assignments)

Writing content for high-stakes texts (e.g., major class assignments, job applications, research articles, grant proposals)

Reading (i.e., summarizing/explaining texts)

Other __________________________________________________

I'm not sure.

Skip To: Q21 If What do you think clients are using them for? (Choose as many as apply.) = I'm not sure.

19. What do you base your selection(s) on (e.g., anecdotal evidence, survey, individual student's input)?

20. Do you think GAI tools (e.g., ChatGPT, Copilot, Gemini, Claude) will change the way writing centers work with clients?

No

Yes

I’m not sure

Skip To: Q22 If Do you think GAI tools (e.g., ChatGPT, Copilot, Gemini, Claude) will change the way writing centers work with clients? = Yes

Skip To: Q23 If Do you think GAI tools (e.g., ChatGPT, Copilot, Gemini, Claude)ts will change the way writing centers work with clients? = I'm not sure.

21. Why not?

Skip to 23

22. How much do you think they will change the way writing centers work with clients?

Not much

Some

A lot

100%--everything has to change.

22. How will they change the way writing centers work with clients?

23. Do you think GAI tools (e.g., ChatGPT, Copilot, Gemini, Claude) will change the way writing center consultants/tutors are trained?

No

Yes

I’m not sure.

Skip To: Q25 If Do you think GAI tools (e.g., ChatGPT, Copilot, Gemini, Claude) will change the way writing center consultants/tutors a... = Yes

24. Why not?

Skip To Q29

25. How much do you think it will change the way consultants/tutors are trained?

Not much

Some

A lot

100%--everything has to change

26. How will they change the way consultants/tutors are trained?

27. Generally, how do you feel about the impact of GAI tools (e.g., ChatGPT, Copilot, Gemini, Claude) on writing centers?

Very negative

A little negative

Neutral

A little positive

Very positive

There is no impact

28. If you would like, explain your answer:

29. Does the institution you are affiliated with have any policy/policies about using GAI tools (e.g., ChatGPT, Copilot, Gemini, Claude)?

No

No, but (a) university-wide policy is/policies are being developed.

Yes, but only for parts (e.g., programs, individual professors)-not university-wide

Yes, university-wide

I'm not sure

Other __________________________________________________

Skip To: Q33 If Does the institution you are affiliated with have any policy/policies about using AI chatbots? = No

Skip To: Q33 If Does the institution you are affiliated with have any policy/policies about using AI chatbots? = I'm not sure

30. Please, describe the policies and who developed/is developing them:

31. At the institution that you are affiliated with, is there support (e.g., workshops, handouts, lists of resources) for using GAI tools (e.g., ChatGPT, Copilot, Gemini, Claude)?

No

No, but support is being developed.

I'm not sure.

Skip To: Q33 If At the institution that you are affiliated with, is there support (e.g., workshops, handouts, lists... = No

Skip To: Q33 If At the institution that you are affiliated with, is there support (e.g., workshops, handouts, lists... = I'm not sure.

32. Please, describe the support and who developed/is developing it:

33. Do you personally use GAI tools (e.g., ChatGPT, Copilot, Gemini, Claude)?

No

Yes, a little

Yes, sometimes

Yes, a lot

Skip To: Q36 If Do you personally use GAI tools (e.g., ChatGPT, Copilot, Gemini, Claude)? = No

34. Which one(s) do you use, and what do you use it/them for?

Display This Question:

If Do you personally use GAI tools (e.g., ChatGPT, Copilot, Gemini, Claude)? = No

35. Why not?

36. If there is anything else you would like to add, please, write it in the field below:

Appendix E

Interview Questions ELSO Tutoring 2023

You filled out a survey at the end of spring semester, do you want to explain or expand on any of your answers?

Please, tell us about your experiences with or opinions of using an AI chatbot to help you with writing.

Please, talk about the ELSO schedule. Was it easy to use? Did you find an open appointment when you want to make one?

If you’ve had ELSO tutoring sessions, please, tell us how they went:

Do you have any suggestions how we might improve our tutoring service?

Appendix F

Follow-Up Interview Questions for ELSO Writing & Presenting Tutoring Study 2023

How has your use of GAI chatbots changed since we talked in May?

Which GAI chatbots have you tried?

What have you found GAI chatbots most & least useful for? Has your opinion changed since we talked in May?

How does working with a GAI chatbot compare to working with a tutor?

Regarding GAI chatbots, has information, rules, guidelines and advice from your professors, program, department, & university changed since May?

Do you think a tutor could help you work with a GAI chatbot? If not, why not? If yes, what do you think a tutor could help you work with?

Do people you know use GAI chatbots for writing? If so, what for and did they say about them?

Do you have any ideas on how ELSO tutors might work more effectively in this new era of GAI chatbots?

How do you feel about using GAI chatbots in the future? At school? In the workforce?