Praxis: A Writing Center Journal • Vol. 22, No. 3 (2025)

Untapped Potentials: Leveraging Disciplinary Expertise for Graduate Writing Consultant Education

Vicki R. Kennell, PhD

Purdue University

vkennell@purdue.edu

Ashley Garla, MA

Purdue University

ashley.garla1@gmail.com

Genevieve Gray, MS

Purdue University

genevieve.gray505@gmail.com

Abstract

Reflecting on the experiences of two graduate students from speech-language pathology (SLP) who became generalist writing consultants, this article examines the intersections between the academic homes of generalist graduate consultants and their writing center education and work and analyzes what these intersections tell us about consultant education. We briefly introduce SLP and identify the specific ways that both fields address writing. We then explore how the disciplinary intersections enhance or hinder the work that graduate students do in either field. Based on this foundation, we propose a four-step process for educating graduate consultants that promotes an awareness of how similarities enhance work in either field, how differences can hinder the work, and how bidirectional transference between fields can benefit graduate students as both consultants and as academics in their home discipline. Ultimately, this paper highlights the untapped potential of the theory and pedagogy of consultants’ home disciplines for effective generalist consultant education.

Introduction

A common topic that arises in conversations among graduate communications scholars is the importance of specialist feedback for graduate writers (e.g., some writers prefer content-knowledgeable consultants; Phillips 163). From a writing center perspective, such conversations presuppose a certain context—having the resources for a graduate-only writing center—a situation in which many writing centers do not find themselves. For most writing centers, graduate writers, if allowed at all, must be folded into the customary peer-tutoring model, where consultants work with writers from all disciplines, but the consulting staff may not possess that disciplinary variety. The need to work with writers across disciplines has led to writing center discussions similar to graduate communications scholars’ conversations about specialist feedback, but with a tendency to favor generalist options. In 1998, Kristin Walker proposed genre theory as a way to fashion a middle ground between generalist and specialist consulting. Layne Gordon revived this theme in 2014, the same year that Sue Dinitz and Susanmarie Harrington’s research clarified the role (and value) of disciplinary expertise in consultations. In 2017, Tomoyo Okuda explored the varying usefulness of generalist strategies, noting a need for improved training of generalist consultants. More recently, in 2021, several chapters of Megan Swihart Jewell and Joseph Cheatle’s book Redefining Roles explored issues related to hiring graduate consultants from across campus, including discussions of how to train them, but also raising once again the generalist versus specialist dichotomy.

Centering the generalist-specialist conversation around what is best for writers excludes issues that affect writing centers generally or consultants specifically. Scholars have noted that the logistics of hiring enough consultants for precise disciplinary matches are problematic for writing centers (Dinitz and Harrington 95). Even where specialist matches are possible, assuming that consultants arrive at the writing center with existing expertise in disciplinary expectations around writing is problematic; even graduate consultants (GTAs) may still be in the process of becoming enculturated into their field of study and may not possess a fully formed or confident expertise. Focusing on content specialization also does not take into account graduate students’ wide-ranging concerns around writing. Graduate writers tend to be savvy about developing feedback networks to address that range. For instance, they may reserve their advisor’s time for dissertations and seek consultant help with more general concerns such as funding applications or sentence-level issues (Mannon). Generalist consultants can also offer value as fellow graduate students; they are familiar with academic research and project management and able to commiserate over the more emotional aspects of writing such as lack of confidence and a tendency to procrastinate. The shared experiences of graduate school contribute to generalist graduate consultants being well positioned to offer valuable writing support regardless of disciplinary match.

Focusing the generalist-specialist conversation on what each type of consultant offers also leaves open the question of what each might need from their writing center education and professional development experiences and, in particular, what graduate consultants might need. In 2019, Katrina Bell noted that very little advice about preparing students to work as consultants specifically addresses the preparation of graduate consultants. Consultant education often focuses on types of writers (e.g., anxious writers, multilingual writers), types of documents (e.g., literature analyses, lab reports), and types of situations (e.g., unresponsive or antagonistic writers) in addition to covering session protocols and the writing process (as an example, see Ryan and Zimmerelli). Such a broad range of material related to consulting with writers can be useful, regardless of whether a consultant is an undergraduate or graduate or is hired as a specialist or generalist. However, just as the generalist-specialist discussion tends to ignore consultants’ needs, so material on educating consultants tends to ignore graduate consultants’ need to successfully integrate work in their home disciplines with work in the writing center. Discussions of home disciplines often focus on the outcomes for writers when consultants share their disciplinary background (e.g., benefits of shared background versus too-directive tutoring; Dinitz and Harrington 89-90). In this article, we focus on what has often been left out of the generalist-specialist and consultant education conversations as it relates to graduate consultants themselves: the specific intersections between the academic homes of generalist graduate consultants and their writing center training and work, and, in particular, what these intersections might tell us about consultant education.1

In recent years, the Purdue OWL has experimented with hiring and educating graduate students from outside English to work as generalist writing consultants. During the 2023-24 academic year, we hired four graduate consultants from outside of English: a doctoral student from math education, a doctoral student from counseling psychology, and two master’s students from speech-language pathology (SLP). Two factors contributed to the specific formation of this first cohort. At Purdue, master’s students tend to be less well funded than doctoral students, making them a common source of applicants. Also, while departments may allow doctoral students to work outside the department when departmental funding has contracted, they generally prefer to have students take assistantships in the department when possible. In fact, we lost one of our doctoral consultants during the fall semester when funding tied to her field of study became available. Our experiment filled the consultants’ need for funding and the OWL’s need to expand the potential pool of GTA applicants due to institutional shifts that particularly affected the humanities. For this first cohort from outside English, new GTA education was only slightly changed from previous years.

As the cohort discussed their experiences of being trained as generalist writing consultants, it became obvious that their home disciplines allowed them to bring expertise to their role that had not been considered when planning the training curriculum and, as a result, was not leveraged to develop them as confident, skilled consultants. In order to illustrate the effects of the intersections between the two forms of expertise, we will focus our discussion on SLP, the home discipline of co-authors Ashley and Genevieve, two of the graduate hires at that time.2 Their training as writing consultants, and hence much of our discussion about disciplinary intersections, was overseen by Vicki, an associate director in the writing center and the other author of this article.

When we first began this project, Ashley and Genevieve were graduate students in the Department of Speech, Language, and Hearing Sciences who were training to be SLPs. They sought employment at the writing center during their first year in their program because of interest in and experience with writing. The vast majority of the writers and documents they worked with fell outside their academic field, so they operated as generalist consultants. However, they also found that their specialist SLP training provided a unique perspective that supported their work with writers. In this paper, we outline the ways in which writing center work and SLP work intersect, beginning with the specific way that both fields address writing and progressing to broader interactions between the fields. In particular, we explore how disciplinary intersections can enhance or hinder the work that graduate students do in either field. We will end by presenting recommendations for writing center administrators seeking to train graduate consultants from academic fields outside of English.

First, a note about terminology. Looking at the intersections of two fields means that we must introduce multiple characters who occupy sometimes-similar roles. For clarity, we will use the following terms to describe our identities as well as those of the people with whom we work: consultant for our role in the writing center; clinician for our role in providing speech therapy services; writers for those we work with in the writing center; and patients for those we work with in the SLP clinic. In discussions pertaining to both consultants and clinicians, we will refer to this collective group as practitioners; and in discussions pertaining to both writers and patients, we will refer to this collective group as clients.

SLP and Written Language

To those outside the field, SLPs are commonly known as the people who help children with their /r/ and /s/ sounds; however, speech is only one aspect of what SLPs are trained to treat. More broadly, SLPs treat language disorders, which range from children struggling to learn and implement the rules of grammar (e.g., omitting -ed for past-tense verbs) to adults with acquired brain injuries relearning sentence structure and parts of speech. Especially pertinent to our discussion, SLPs also address patients’ writing. The reciprocal relationship between oral and written language has been well-documented, building the basis for the SLP’s scope of practice to include both modes of communication (Summy and Farquharson). Children with developmental communication disorders and adults with acquired language disorders often demonstrate difficulty in some aspects of written language as well as spoken language. SLPs therefore diagnose disorders of reading and writing, including dyslexia; establish collaborative relationships with educators to foster students’ written language; and work to prevent academic difficulties that result from difficulties with written language (“Written Language Disorders”). For both written and spoken language, SLPs aim to empower patients to effectively communicate their needs and wants regardless of modality.

Intersections between SLP and Writing Centers

While the overlap between the SLP and writing center fields is most salient in the way that both disciplines deal with written language, intersections extend beyond this explicitly common ground. For any given consultant—in our case those from SLP—three potential intersections may occur between their home discipline and the writing center:

both fields may approach an aspect of working with writers in a similar manner,

both fields may differ (and likely conflict), or

the work in one of the fields may unexpectedly transfer to and enhance the other.

When both fields have a similar approach, the new consultant may experience increased confidence in consulting with writers, comfort with writing center work, and an easy transition from clinician (in the case of SLP) to consultant. When fields conflict, it can create unease and decrease confidence in working with writers. Differences do not necessarily have to mean conflict, however. When consultants either bring something from their home discipline to their writing center work or carry something from the writing center to their home discipline, the field on the receiving end benefits from an infusion of new ideas, methods, or potential areas for research. Exploring and leveraging these similarities and opportunities for transfer between fields during training and beyond can help facilitate a more effective and time-efficient transition from clinician to consultant.

Similarities

Several similarities between SLP work and writing center work allowed us to transition fairly seamlessly from one to the other. Both fields value professional development of their staff, offering training that combines theories and pedagogies of the field with supervised client interaction. For instance, SLP students gain hands-on practice in education and healthcare settings where they assess and treat patients and apply evidence-based strategies to real-world scenarios, while new writing consultants observe and co-tutor live sessions. In both fields, training requires openness to feedback and emphasizes personal reflection. Our training also involved being observed during a session by a more senior practitioner (writing center administrator or clinical supervisor) and receiving feedback on strengths and areas for improvement. Additionally, reflecting on sessions to process them and think through next steps was an essential element of developing our ability to self-assess our effectiveness as we continued to engage with clients in both fields.

The fields also share similar approaches to writing and to supporting writers. Both understand writing as a process from pre-writing through revising, although the terminology varies. For instance, while SLP distinguishes between “process” (e.g., developing ideas, planning, organizing) and “product” (e.g., written form, syntax, effectiveness of intended communication) (“Written Language Disorders”), the writing center views addressing grammar as part of the writing process. In addition, both fields share methods of supporting writers, such as scaffolding to help clients learn to recognize their own errors (patients) or areas for revision (writers) without our input. Clinicians might help a patient with difficulty swallowing to better understand the link between their actions and their body’s response through biofeedback methods such as visualizations of muscle activation (Archer et al. 282). Consultants might move a writer from depending on consultant input for correctly formatting citations to referencing style guides independently. As with approaches to writing, although the strategy may be similar across fields, the terminology varies. While writing centers commonly talk about scaffolding (e.g., I do, we do, you do), SLP divides that into specific strategies like modeling (e.g., demonstrating the correct production of a speech sound) and cueing (e.g., reminding the patient to pay attention to their tongue when attempting the sound). In both cases, however, the strategies are geared toward helping clients acquire, practice, and gain independence with their ability to communicate.

These similarities in both professional development and approaches to writing arise naturally because the underlying focus of both fields centers the client while working toward the overall goal of skill and knowledge transference (writing centers; e.g., see Devet’s transference primer) or generalization (SLP). For instance, writing center consultations help writers think about their own writing and also about disciplinary writing, topics that Elizabeth Wardle suggests are necessary for transfer to occur (82). In both fields, clients ideally receive writing instruction from other sources, and our role is to provide scaffolding to what happens outside our space. SLP pull-out programs allow for individualization and focus on specific skills in ways that still coordinate with classroom instruction (“School-Based Service Delivery”). Consultants collaborate with instructors implicitly, by encouraging writers to share materials such as instructor feedback and assignment sheets. Despite the implicit presence of other educators, the aim of sessions in either field is not to tailor strategies to specific features of an assignment or educator expectations but rather to provide input that aligns with the current assignment while also encouraging writers to develop meta-awareness about writing. In our case, the presence of similarities around approaches to working with clients—and around writing more generally—allowed a relatively smooth transition from clinician to consultant; however, the positive result was serendipitous rather than planned. Overtly focusing on the similarities during early training might have allowed us to gloss over the basics more quickly, leaving time to explore other aspects of writing center theory and pedagogy more deeply.

Differences

While similarities between the fields helped us effectively engage with clients at the writing center and in the clinic, unexplored differences created moments of difficulty. One of the most immediate differences was the expected amount of preparation prior to a session. When we were told not to extensively prepare for a writing center session, we felt uneasy. As health professionals, we are expected to thoroughly prepare beforehand in order to achieve the best results. The clinician is held accountable for the patient’s progress by schools, healthcare facilities, and other oversight bodies. Failure to prepare could lead to reprimands from supervisors and conflict with clients. As new consultants, we did not yet understand or have the opportunity to discuss how this little-to-no-prep policy can actually help facilitate a more collaborative and writer-led session. Discussing this difference during training would have reduced our early discomfort while simultaneously enhancing our ability to create highly collaborative sessions with writers.

Most of the differences that interfered with our work resulted from different understandings of the practitioner’s role. In SLP, we were expected to act as an expert, giving feedback that is fundamentally assertive (e.g., “Round your lips more while saying the sh sound”) and evaluative (e.g., “When you said red your r sounded more like a w”). In the writing center, we were encouraged to serve as peers and, in particular, as generalist peers. This contrast in how the practitioner is positioned with respect to the client resulted in an unexpected lack of confidence when relating to writers in a one-on-one setting. Because we were accustomed to a similar one-on-one context in SLP, we found the differences in power dynamics between the two fields disconcerting. In our expert SLP role, we determine the trajectory of a patient’s treatment, including the number of sessions, while both measuring and assuming responsibility for the outcomes. In contrast, in our peer consultant role, our work is much more dictated by the writer’s goals and how they feel about the session, regardless of how incremental their progress might seem to us.

Due to the shared people-facing and one-on-one interaction contexts of the two settings, we did not discuss the differences in style of interaction in our training. As we became increasingly aware of similarities between the fields and leaned into those, it was easy to make assumptions about what else may carry over. This lack of focus on differences between fields resulted in missteps in both settings. As consultants, we periodically found ourselves second-guessing how much expertise we should claim. For example, Genevieve felt afraid to be too direct with writers, which led to long moments of silence while she pondered how to provide feedback without taking away writer agency. Similar problems occurred with our SLP work. During the first semester of Ashley’s graduate program, a clinical supervisor told her that she needed to be more assertive in therapy sessions, leading her to realize she was approaching therapy like a writing consultation. While discomfort is often unavoidable when learning something new, discussing differences during training would have helped identify the why behind our unease, leading to quicker resolution. In addition, explicit focus on differences would have allowed us to move between the different roles consciously, taking up or leaving behind particular styles or methods in context-appropriate ways.

Bidirectional Transference

When we think about intersections between fields of study, it is worth considering both what the consultant brings to their writing center work from their home discipline and also how the writing center work can affect the home discipline in return. Writing centers staffed primarily by English graduate students often consider themselves an integral part of those students’ professional development, as GTAs may first work in the writing center before teaching composition. This career trajectory will not be the same for GTAs from outside English, but the principle still holds: The work the consultants do in the writing center should benefit their future careers. In turn, the knowledge and experience that GTAs bring from their home discipline can enhance writing center theory and pedagogy.

From SLP. As SLPs, Ashley and Genevieve brought to the writing center more than just the similar experiences with one-on-one sessions or methods like scaffolding. Even though generalist tutoring encourages moving away from a focus on the individual consultant’s academic background, one of the specific contributions that a consultant from outside of composition brings to writing center work is a potential breadth of knowledge across multiple fields. For instance, SLPs must know not only about diagnosing and treating communication disorders but also have a foundation in areas like psychology and linguistics. Similarly, consultants from disciplines such as engineering might have a breadth of knowledge across fields like math and physics. The broad academic background of those outside the composition field leads to comfort and familiarity with content and writing conventions across multiple related but distinct fields, potentially lending a specialist quality to their generalist consultations with writers from a variety of backgrounds beyond their own.

In addition to content knowledge, SLPs have an awareness of individuals that can enhance writing center pedagogies. As SLPs, we are aware that an approach may be extremely effective for one client, but completely disruptive to another. SLPs are taught to pay attention to the patient’s needs as both a member of a specific population (e.g., patients with aphasia benefiting from shorter, less complex statements) and as an individual (e.g., a patient’s preference for a high-energy or low-energy environment). While the populations and individual needs of writing center clients do not align directly with those in the SLP setting, this awareness allowed us to embrace rather than fear the potentially inconsistent nature of consultations.

For writing centers, perhaps the most valuable aspect of the SLP’s awareness of individual needs is the way in which it positions them to challenge practices that allow consultants to remain in their own comfort zone at the expense of clients. For example, reading a writer’s document aloud is a common writing center practice because it can be extremely helpful for identifying places that need work. It can be disconcerting for consultants when a writer rejects the practice. Similarly, consultants might expect writers to behave and communicate in certain ways, to make eye contact or use nonverbals to show they understand what we are saying and to demonstrate engagement. When expectations are not met, consultants tend to feel uncomfortable, and the session can derail quickly. This is a circumstance which SLP training is perfectly situated to address.

SLP clinical training taught us that a session's goals can be achieved even if the methods look unconventional because communication comes in many forms and does not look the same for everyone. This perspective has informed our writing center work. Because we see communicative variety exhibited in real life through our work with patients, we are attuned specifically to the interpersonal communication needs of our clients in either field. We also understand that there can be many co-existing factors that influence a patient’s ability and willingness to express themselves, whether that be a diagnosed condition (e.g., ADHD, dyslexia, ASD) or patient preferences. Experience working with patients who have different ways of communicating and who often exhibit frustration with their ability to communicate has given us a perspective that not only benefits our own consultations with writers but can also be shared with other consultants. An SLP focus on meeting patients where they are in terms of oral communication combines with the writing center's concern for meeting writers where they are in terms of written expression, creating an enhanced experience for both client and consultant.

A final potential area of transference from SLP to writing center work can be found in relationships with faculty as well as students. For writing centers which offer faculty-requested workshops or who administer (or aspire to administer) a writing fellows program, consultants from SLP bring a unique perspective on interprofessional collaboration. SLPs are increasingly expected to work closely with teachers and classroom staff within the general education classroom or to provide coaching to relevant educators on how to promote specific skills (Archibald). This background of collaborating closely with other educators might transfer nicely to a writing fellows situation where the consultant needs to work collaboratively with a faculty member to meet course writing goals while occasionally redirecting an instructor’s misplaced enthusiasm for how such a program best operates.

From Writing Centers. While leveraging existing strengths affects how we might educate new consultants, an equally important issue to consider is what they learn from us that might benefit their alternate academic life. One direct benefit that we derived from the writing center was experience talking and thinking about writing strategies. Genevieve found her SLP literacy class less intimidating because working in the writing center had introduced her to writing best practices and provided experience talking with a wide range of writers. As we worked with writers, we also gained practice with concepts that helped our own writing as students and future professionals. Working as consultants gave us a better understanding of the importance of considering the intended audience, which helped greatly as we wrote final research papers for our program. We were better able to adjust discipline-specific information to be more accessible for colleagues.

In addition to technical ability, we further developed our interpersonal skills. Our experience making writers feel comfortable has translated into being better equipped to support patients during times of vulnerability or doubt. In learning to provide feedback to writers in a supportive yet helpful manner, we have further refined our ability to offer compassionate and clinically effective feedback to the patients we serve. For example, two semesters after Ashley was instructed to be more assertive in a clinical setting, a different supervisor encouraged her to be less assertive and to use more “I wonder” phrases. Due to her familiarity with this exact phrasing while consulting with writers, she was able to easily adapt to this change in feedback style while in the clinic.

One of the differences we talked about earlier as causing unease led to eventual gain. While going into writing center sessions without a designated plan was daunting at first, practice doing so fostered an ability to improvise that has increased our flexibility during SLP sessions. Our clinical training conditions us to view a successful session as one that begins with a perfectly crafted lesson plan and follows that through, which does not always reflect reality. Our time at the writing center showed us that even when things do not go as planned, we have experience and techniques we can rely on to help us recalibrate and problem-solve. Experience responding to writer needs as they emerge and making effective decisions in the moment have helped us realize that some of the best sessions arise from changing course. In clinical sessions, this translated to remaining calm and adjusting rather than freezing during unexpected bumps. Being able to change course effectively and intentionally has not only served us as clinicians but also highlights the larger point that transference between fields, while it may contribute initially to practitioner unease, has the capacity to enhance the work of both fields.

Implications for Graduate Consultant Education

The intersections we have identified between SLP and writing center work will not map precisely across all fields; however, they do point to important considerations when educating graduate students in the role of generalist consultant. Students like Ashley and Genevieve do not enter the writing center space as blank slates when it comes to writing or talking about writing, but neither do they automatically possess confidence in their own experiences and abilities. In addition, we are essentially asking them to regularly switch between the theories and pedagogies of two very different fields, to, as Christopher LeCluyse and Sue Mendelsohn point out, “take on the persona and responsibilities of a confident professional” in each role (103). As we consider how best to develop them as confident, successful consultants in the writing center, it is important to see the process as a two-way mentorship. The experiences and education that graduate consultants bring from their home discipline have ramifications for the work they do in the writing center, but the reverse is also true. What they learn during their time in the writing center has potential ramifications for the work they do in their home discipline as well. The professional development we offer in the writing center should follow Bell’s definition: “not only to meet current institutional and individual needs, but also to move participants toward their professional goals.” As such, writing center professional development should consist of acknowledging the tools already at graduate students’ disposal from their home disciplines while simultaneously adding to rather than replacing them. What and how we teach should leverage similarities for increased confidence in both fields, identify differences in order to circumvent potential conflicts between fields, and enable graduate consultants to shift between roles smoothly and appropriately. We propose a four-step process for educating consultants from outside the writing center field: awareness, discussion, reflection, and dissemination. Although pedagogies such as discussion and reflection are common within writing center education (e.g., Julia Bleakney notes that “reflection is a touchstone of ongoing tutor education”), each step here involves a closer look at the three potential intersections between fields we identified earlier.

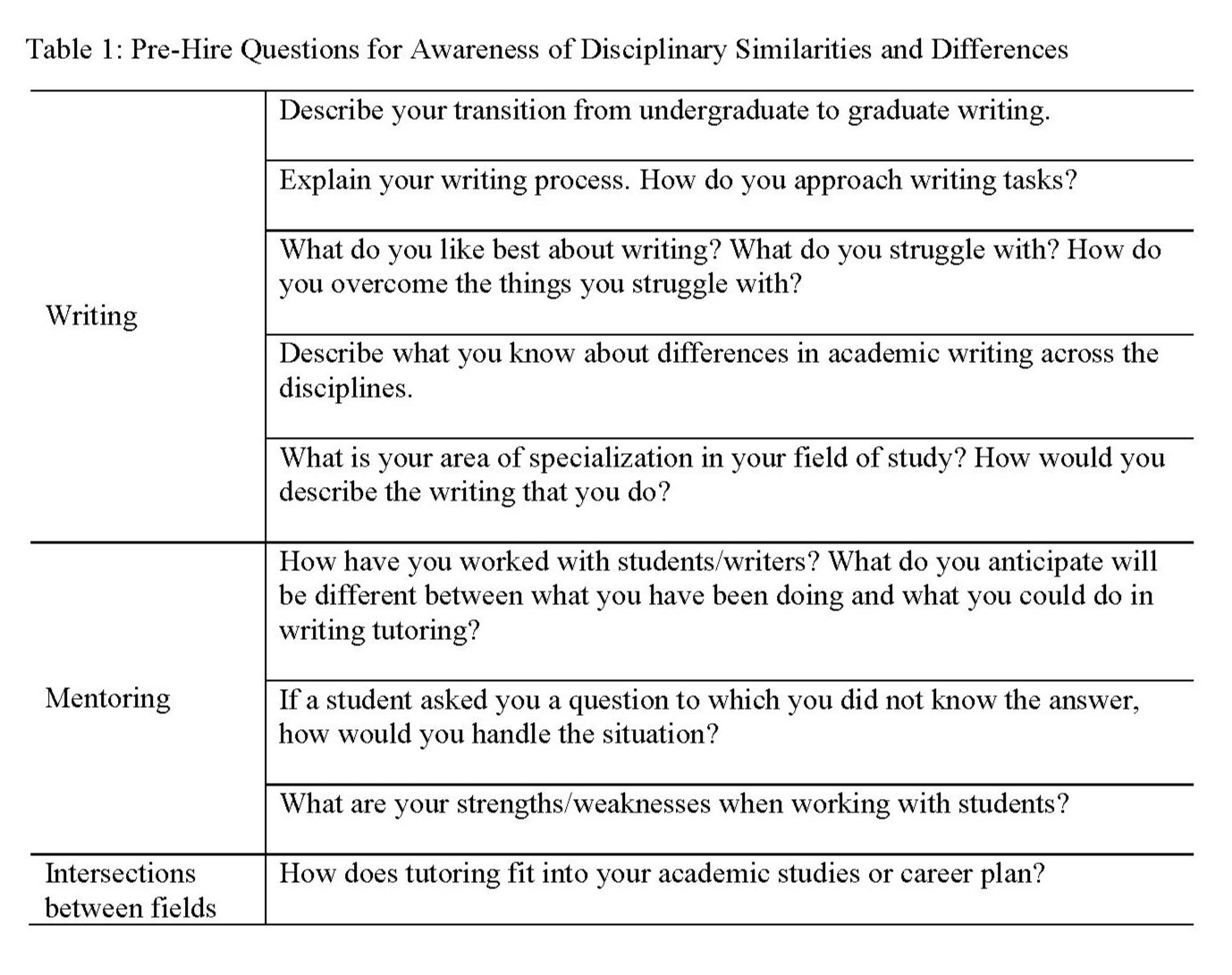

The first step, awareness, can occur even before the consultant is hired. In our writing center, GTAs must apply and be interviewed before being hired. Vicki commonly includes questions in that interview that ask applicants to think about their current position with respect to writing and mentoring students but also to explain how working for the writing center fits into their academic studies or career development. Potential questions focus on topics such as their own transition from undergraduate to graduate writing, what they like best about writing, and how they would support a writer who asked a question to which they did not know the answer. These topics can provide insight into how applicants think about writing, mentoring, and their own abilities. Table 1 provides a more detailed breakdown of the types of questions that might be asked. Answers to questions such as these offer valuable insight to the one doing the hiring, but they also nudge the applicant to consider potential intersections between their home field and the writing center. Talking about differences in academic writing across disciplines, for instance, opens the door to realizing that other forms of similarity and difference might exist. The awareness raised by these early questions is the first step toward paying explicit attention to how the two academic domains might interact.

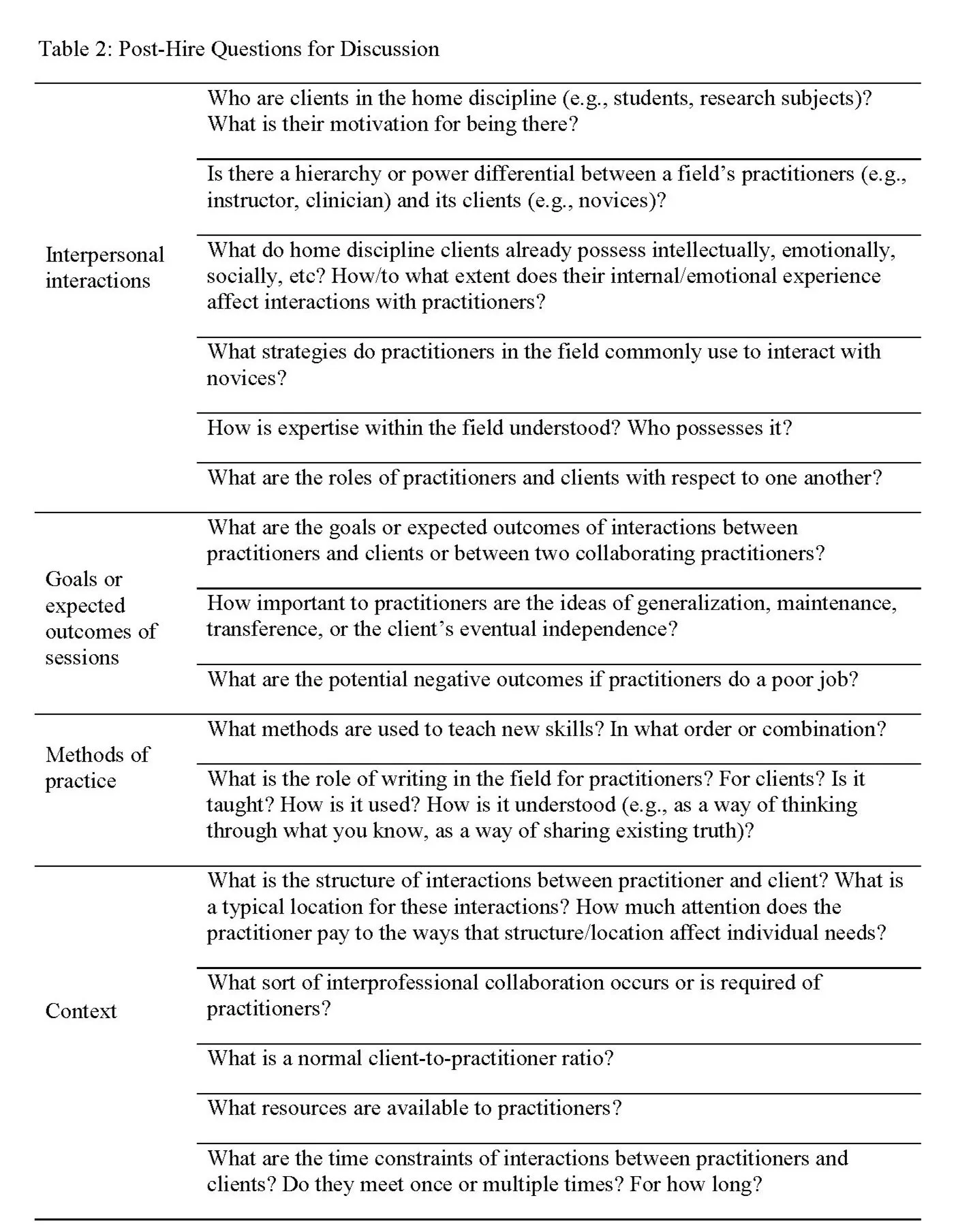

The second step, discussion, occurs during orientation and early training. In our case, initial professional development took place the week prior to and during the first five weeks of the semester. Explicitly exploring the similarities and differences between fields serves as a useful way to bolster consultants’ confidence in the abilities they already possess and in their ability to acquire new expertise while also helping them avoid assumptions that might hinder their success as consultants. For Ashley and Genevieve, openly exploring the similarities between SLP and writing centers, such as protocols for one-on-one sessions, helped them adjust their understanding of their starting point from “knows nothing about writing consultations,” a position that undermined confidence, to “has experience with one-on-one sessions with clients,” a position that restored confidence. Similarly, discussing differences such as power dynamics, time constraints, or the regularity of sessions would have made the differences less likely to create roadblocks to success in either setting. Discussion of topics related to interpersonal interactions, goals for sessions, methods of practice, and context allows for immediate application of home discipline experiences to the new setting, avoidance of potential hindrances, and the transference of useful material from one field to the other.

As an example, we might think about relational aspects such as power dynamics between practitioner and client as one area of overlap. In fields such as math education (teacher-student) or counseling psychology (therapist-patient), thinking of relational interactions as an area of overlap makes immediate and obvious sense. If the graduate consultant comes from a field without such obvious practitioner-client relationships, discussing relational aspects is still important; many fields will require researcher-subject interactions, and most will involve some amount of expert-novice interaction. Some will involve co-authoring interactions. Any of these relational aspects of a field may result in the sorts of similarities or differences explored by the questions we have listed in table 2. Without explicit discussion, the introduction to writing center theory and pedagogy may be subverted by unexplored aspects carried over from the home discipline or may itself compromise the consultants’ work in that other discipline.

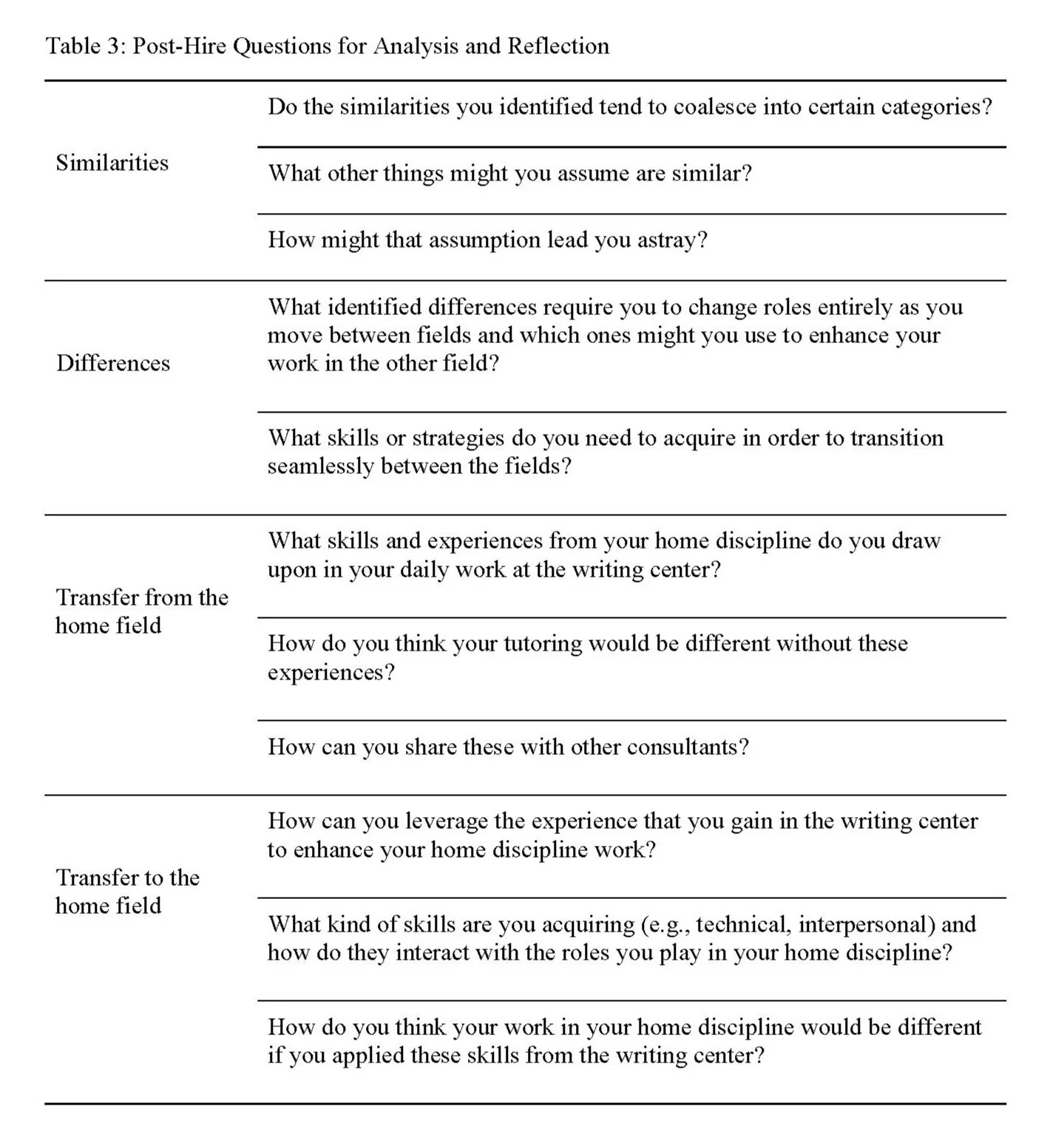

The third step, reflection, should be ongoing for the duration of a consultant’s employment with the writing center and should encourage them to analyze the significance of similarities and differences while considering whether material from one field might transfer to the other. Asking consultants to reflect regularly on disciplinary intersections allows a responsiveness to changes arising in the home discipline that may also affect their thinking about intersections between the fields. For instance, Genevieve would have found it difficult to consider the similarities in how writing was approached in both fields when she first started working in the writing center because she had not yet taken her department’s literacy class. Ongoing reflection should center around how and when to switch between writing center practitioner and, in our case, SLP practitioner. Much like writing center administrators ask consultants from composition fields to think through the similarities and differences between teaching or creative writing workshopping and consulting, consultants from non-English fields can be encouraged to think critically about their two roles and to consider what might be imported from their home discipline that furthers writing center goals and what might need to be left at the door each time they move between fields. Analysis might focus on similarities that can lead to assumptions, on differences highlighting strategies that still need to be acquired, or on aspects that might transfer from one field to the other, i.e., how work in the home discipline might be different if writing center principles were applied there. The discussion could cover a broad range of issues such as we have explored here and have itemized in table 3.

The final step, dissemination, asks consultants to deepen their participation in writing center culture beyond simply supporting writers. Megan Boeshart Burelle and Meagan Thompson’s heuristics for graduate consultant training suggest that encouraging GTAs to teach other consultants helps them understand their position as one of personal professional development (250). As we have discussed, the knowledge and experiences graduate consultants bring from their home discipline can be valuable to other writing center practitioners. In considering how to use consultant education to enable GTAs to share what they know with other consultants, we not only address Burelle and Thompson’s heuristic but also position GTAs in the role that Kristin Messuri invites them to occupy, that of “disciplinary ambassador” (217). While Messuri focuses primarily on sharing disciplinary aspects of writing, we suggest that ambassadorship might move beyond just writing knowledge. Encouraging graduate consultants to also share what they know about interpersonal interactions and methods of practice with fellow consultants or through conference presentations both consolidates their own understanding of what they possess and also passes it on to other writing center practitioners.

Here, too, consultants will be considering questions of transference, of what sort of cross-pollination between fields might benefit them both. For instance, consultants from SLP might lead a staff meeting to share strategies for approaching sessions with writers who do not display their engagement in expected ways. In addition, what consultants from outside the field bring to their consulting might stretch the boundaries of writing center scholarship. From SLP, for instance, we might be encouraged to take a closer look at consultants’ roles vis-à-vis their clients: For whom and under what circumstances might it be beneficial to act as an expert rather than a peer? How does each role benefit or hinder a writer? Writing center scholarship about disability might also benefit from an approach that borrows from the SLP lens. For instance, what techniques (e.g., using shorter, less complex sentences) might consultants borrow for any session where communication with a writer seems difficult? Disseminating what they have discovered about the similarities, differences, and transference between their two fields bolsters the GTAs’ development as consultants, as practitioners in their home field, and as academics more generally.

Conclusion

We began this article by labeling Ashley and Genevieve’s cohort an experiment in training graduate consultants from outside English. Such a label implies an element of evaluation: How well did the experiment work? From Vicki’s administrative standpoint, it worked extraordinarily well, despite the serendipity of cross-disciplinary connections occurring without advance planning. The consultants were there because they chose to be rather than because working at the writing center was the expected next step in their funding. Unlike English GTAs from previous years, consultants were thoroughly vetted through the application process rather than placed in the writing center because they needed to gain necessary skills or professionalism before entering the classroom. And, as we have explored here, the consultants brought additional, unanticipated value to their work, as well as doing an excellent job as consultants.

From the consultants’ standpoint, Ashley and Genevieve have no regret about having stepped outside their department for funding. They found working at the writing center to be creative, interpersonal work that complemented their graduate studies and allowed them to develop personal mentoring and teaching styles. Working with staff and with writers from across campus helped them expand their professional and personal connections beyond the immediate circle of their graduate program. They were exposed to new disciplines and writing conventions, and they were afforded professional opportunities (e.g., significant experience mentoring undergraduates with writing) and personal mentorship (e.g., presenting at conferences) that the introductory undergraduate course assistantships in their department would likely not have provided. In short, they found the experience of working at the writing center to be helpful with developing broad, non-disciplinary skills.

In the introduction to Re/Writing the Center, Susan Lawrence and Terry Myers Zawacki explain their purpose as helping writing center practitioners “rethink and revise the principles and practices that have been definitional to [their] theory and pedagogy” (9). Although the book focuses primarily on writers and writing, the idea of rethinking our professional practices resonated as we explored the intersections that may occur between fields. Ashley and Genevieve were forced to rethink their own SLP practices as they shifted between roles, but they were also able to challenge definitional writing center practices such as reading aloud.

If we see writing as not only words on the page but also process, thought, communication, collaboration, general yet discipline specific, and a host of other descriptors; if we see writing centers not only as places of teaching, learning, researching, and mentoring but also as places that operate “across the curriculum” and “in the disciplines,” then perhaps we should not be thinking of ourselves as belonging primarily to English nor limited by discipline when hiring GTAs. Perhaps how we hire and how we educate graduate consultants is yet another aspect of Jackie Grutsch McKinney’s call to question our orthodoxies. A wealth of possibility exists if we open our GTA hiring process beyond English, as we have discussed here, but with that wealth comes great responsibility. As we plan to educate GTAs from beyond English, we will want to consider what they need from that education in order to truly develop as cross-disciplinary professionals.

Vicki tells our new GTAs that being a good consultant does not involve particular strategies applied in correct ways; instead, what defines a good consultant is doing something for a reason, paying attention to how well it works, and adjusting as necessary. In other words, consultants must learn to be self-aware and to modulate their interactions with writers appropriately, as Ashley did when navigating the conflicting advice of SLP and writing center supervisors. Hiring GTAs from beyond English brings this need for appropriate modulation to the foreground, and professional development for this group thus requires an attention to both disciplines—the new writing center world but also the familiar home discipline. The result for consultants and writing centers alike will be positive.

In discussing our experience navigating the conflicts and overlaps between Ashley and Genevieve’s academic training in SLP and their work in the writing center, our hope is that our reflections can offer insight to writing center administrators hiring graduate consultants from varied fields. Having an understanding of both the similarities and differences that exist between a consultant’s academic field and writing center theory and pedagogy can help to promote success while also avoiding interference with the best practices of either domain, while paying attention to the possibility of transference between disciplines ensures that potentials do not go untapped.

Notes

When we use the term "intersections,” we are not invoking the theory of intersectionality but rather applying a more conventional usage meaning simply where two things meet. We appreciate other theoretical usages of the term, but they did not guide our work here.

While we wrote this article collaboratively, we will name ourselves in the moments where we must refer to something individually experienced.

Works Cited

Archer, Sally K., et al. “Surface Electromyographic Biofeedback and the Effortful Swallow Exercise for Stroke-Related Dysphagia and in Healthy Ageing.” Dysphagia, vol. 36, 2021, pp. 281-292. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-020-10129-8.

Archibald, Lisa MD. "SLP-Educator Classroom Collaboration: A Review to Inform Reason-Based Practice." Autism & Developmental Language Impairments, vol. 2, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1177/2396941516680369.

Bell, Katrina. “Our Professional Descendants: Preparing Graduate Writing Consultants.” Johnson and Roggenbuck. https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/books/dec1/Bell.html.

Bleakney, Julia. “Ongoing Writing Tutor Education: Models and Practices.” Johnson and Roggenbuck. https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/books/dec1/Bleakney.html.

Burelle, Megan Boeshart, and Meagan Thompson. “An Inquiry-Based Approach for Customizing Training for Graduate Student Tutors.” Jewell and Cheatle, pp. 241-252.

Devet, Bonnie. “The Writing Center and Transfer of Learning: A Primer for Directors.” The Writing Center Journal, vol. 31, no. 1, 2015, pp. 119-151. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43673621.

Dinitz, Sue, and Susanmarie Harrington. “The Role of Disciplinary Expertise in Shaping Writing Tutorials.” The Writing Center Journal, vol. 33, no. 2, 2014, pp. 73-98. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43443372.

Gordon, Layne. “Beyond Generalist vs. Specialist: Making Connections between Genre Theory and Writing Center Pedagogy.” Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, vol. 11, no. 2, 2014. http://www.praxisuwc.com/gordon-112.

Jewell, Megan Swihart, and Joseph Cheatle, editors. Redefining Roles. Utah State UP, 2021. https://doi.org/10.7330/9781646420858.c018.

Johnson, Karen Gabrielle, and Ted Roggenbuck, editors. How We Teach Writing Tutors: A WLN Digital Edited Collection. WLN, 2009. https://wac.colostate.edu/books/wln/dec1/.

Lawrence, Susan, and Terry Myers Zawacki, editors. Re/Writing the Center: Approaches to Supporting Graduate Students in the Writing Center. Utah State UP, 2018. https://doi.org/10.7330/9781607327516.

LeCluyse, Christopher, and Sue Mendelsohn. “Training as Invention: Topoi for Graduate Writing Consultants.” (E)Merging Identities: Graduate Students in the Writing Center, edited by Melissa Nicolas. Fountainhead Press, 2008, pp. 103-18.

McKinney, Jackie Grutsch. Peripheral Visions for Writing Centers. UP of Colorado, 2013. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt4cgk97.

Mannon, Bethany Ober. “What Do Graduate Students Want from the Writing Center? Tutoring Practices to Support Dissertations and Thesis Writers.” Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, vol. 13, no. 2, 2016, pp. 59-64. http://www.praxisuwc.com/mannon-132.

Messuri, Kristin. “Disciplinary Ambassadors in the Graduate Writing Center: A Professional Development Framework for Graduate Consultants from Diverse Fields.” Jewell and Cheatle, pp. 216-28.

Okuda, Tomoyo. “What a Generalist Tutor Can Do: A Short Lesson from a Tutoring Session.” Canadian Journal for Studies in Discourse and Writing/Rédactologie, vol. 27, 2017, pp. 58-68. https://doi.org/10.31468/cjsdwr.580.

Phillips, Talinn. “Writing Center Support for Graduate Students: An Integrated Model.” Supporting Graduate Student Writers, edited by Steve Simpson, Nigel A. Caplan, Michelle Cox, and Talinn Phillips, University of Michigan Press, 2016, pp. 159-170. https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.8772400.

Ryan, Leigh, and Lisa Zimmerelli. The Bedford Guide for Writing Tutors. 6th ed. Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2016.

“School-Based Service Delivery in Speech-Language Pathology.” American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, www.asha.org/slp/schools/school-based-service-delivery-in-speech-language-pathology/. Accessed 17 Nov. 2024.

Summy, Rebecca, and Kelly Farquharson. "Examining Graduate Training in Written Language and the Impact on Speech-Language Pathologists' Practice: Perspectives from Faculty and Clinicians." American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, vol 33, no.1, 2024, pp. 189-202. https://doi.org/10.1044/2023_AJSLP-22-00327.

Walker, Kristin. “The Debate Over Generalist and Specialist Tutors: Genre Theory’s Contribution.” The Writing Center Journal, vol. 18, no. 2, 1998, pp. 27-46. https://doi.org/10.7771/2832-9414.1399.

Wardle, Elizabeth. “Understanding Transfer from FYC: Preliminary Results of a Longitudinal Study.” Writing Program Administration, vol. 31, no. 1-2, 2007, pp. 65-85. http://associationdatabase.co/archives/31n1-2/31n1-2wardle.pdf.

“Written Language Disorders.” American Speech-Language Hearing Association, www.asha.org/practice-portal/clinical-topics/written-language-disorders/. Accessed 17 Nov. 2024.