Praxis: A Writing Center Journal • Vol. 22, No. 3 (2025)

Review of Critical Thinking in Academic Writing: A Cultural Perspective

Jonathan Faerber

Royal Roads University

jonathan.faerber@tuj.temple.edu

Pu, Shi. Critical Thinking in Academic Writing: A Cultural Approach. Routledge, 2023. 184 pages.

Western academics frequently define successful student writing in part by the author’s mastery and demonstration of critical thinking in their texts (Greasley and Cassidy 182). Therefore, in order to support international students coming to English-speaking institutions in the West, post-secondary writing instructors and tutors must understand these students’ diverse contexts and create an environment where these students are able to communicate their critical thinking effectively (Egege and Kutieleh 81). But what does this environment look like, and what are the relevant differences between the cultures of Western academic institutions and other cultures? Are these apparent differences meaningful, and do they influence how students conceptualize critical thinking? If so, how do these students understand or communicate their critical thinking within their own cultures to begin with?

In Critical Thinking in Academic Writing: A Cultural Perspective, Shi Pu thinks critically about these questions and masterfully combines empirical and theoretical research on the topic of cultural differences in learning and writing between China and Western societies, particularly the UK. However, instead of making inferences about students’ critical thinking ability from their cultural identity or their texts, as is sometimes typical in earlier research (Tian and Low 65), Pu develops a more compelling and long overdue account in which these students’ texts reflect the individual goals and environmental factors that influence their attitudes and perspectives on critical thinking.

The argument in this book starts from the premise that critical thinking is a cultural practice—it is “built upon certain views of authorial voice and author-reader relationship” and is “related to views regarding ‘how knowledge is constructed, how knowledge is evaluated, where knowledge resides’ (Hofer, 2002, p. 4), and how knowledge is conceived in relation to learning and personal development” (27). With this assumption in mind, Pu articulates the ways in which the concept and application of critical thinking in student writing depend on individual factors such as institutional requirements and support, cultural expectations, and each student’s motivation to align their own goals with such requirements and expectations.

In order to examine these factors, Pu takes three groups of Chinese students from contrasting cultural or linguistic settings as her primary subject matter (see fig. 1). All students worked towards similar academic credentials (a graduate degree in second language education) and submitted a literature review as a partial requirement for these credentials (Pu 45). However, while two groups wrote their literature reviews in English in two different cultural environments (United Kingdom and China), the third group completed an analogous assignment in Mandarin.

Fig. 1. Comparison of subjects in Shi Pu’s study

Throughout her book, Pu finds that there are indeed apparent differences in how each group understands and demonstrates their critical thinking, both in their literature reviews as well as in the academic and professional decisions they make in order to complete their program (77). The students based in the UK and writing in English generally structured their literature review as an argument in several respects: they argued that their research topic was worthwhile (80), they provided reasons for choosing specific theoretical perspectives over competing alternatives (91), and they frequently articulated salient links between new data and their own perspective (90). This contrasts with the two groups of students in a Chinese institution, who each placed far more emphasis on the choices they were making at the early stages of a literature review (70) and spent more time detailing the historical development of their chosen topic in the literature and explaining the perspectives of the most authoritative sources on the topic (96).

At first glance, these findings appear consistent with previous research on the topic involving similar groups of students (Tian and Low 66). But unlike previous studies, Pu does not conclude from the superficial areas of contrast that these groups of students differ in their capacity to think critically. Instead, Pu suggests that these differences are explained in part by contrasting goals and the students’ perception of themselves: while the UK-based group saw themselves as researchers tasked with producing academic knowledge, the Chinese-based students valued having a comprehensive understanding of the literature and sought to make the best possible choices in selecting the “correct” literature to review (119). In this way, Pu realizes that these disparities result from and reflect the external factors each student was faced with as well as the way they perceive themselves in relation to their writing (139).

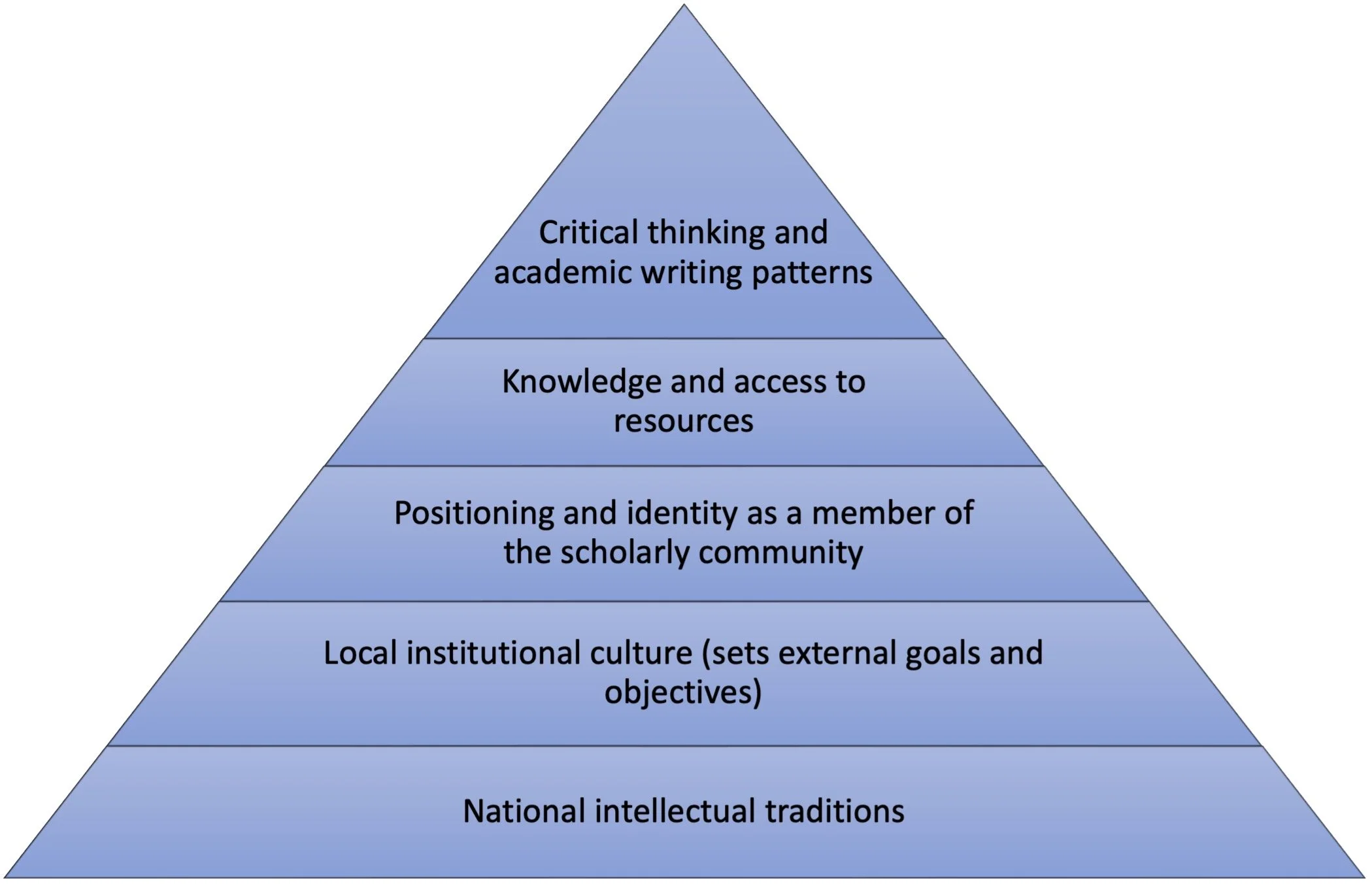

Therefore, in the model below (see fig. 2), differences in writing patterns are not a straightforward consequence of students’ capacity to think critically, but instead rooted in factors that are somewhat independent of students’ intellectual capabilities and outside of their control.

Figure 2. Hierarchy of Influences on Student Writing

For instance, while the UK-based students had direct access to literature in the English language and detailed resources and requirements, they also had significant autonomy to determine their own topic and to set their own research objectives (126-127). As a result, these students were more likely to see themselves as part of the English-speaking academic community (130). By comparison, the China-based students had limited institutional resources and requirements related to writing a literature review in the style of a so-called critical thinker (which is to say, a critical thinker as defined by Western academics). In addition, they were often unable to access, read, or understand the Western literature in their field and often worked on topics proposed by their supervisors (120). Therefore, from their perspective, they understood themselves to be positioned as academic novices at the very periphery of a Western-dominated scholarly community of critical thinkers, and they therefore were more likely to take on the role of a learner or practitioner rather than a researcher (136).

Viewed from this perspective, the degree to which students adopt Western approaches to critical thinking in their texts is related to their identity and autonomy as a researcher and their attitude towards the academic community, as well as their access to relevant resources. When “critical thinking” is portrayed as a defining part of the Western academic tradition, as it is in Dam and Volman (360), students who feel excluded from Western cultures may conclude that they also do not belong to the academic community (Pu 132). It is therefore natural for them to resist or doubt their own ability to internalize what they see as a foreign practice, as noted above and illustrated below (see table 1).

Table 1

Impact of Community and Autonomy on Student Motivation and Confidence

Unfortunately, Pu does not comment on the applicability of these findings to other cultural contexts, but it may be possible to analyze similar outcomes in other groups of students analogously. For example, even within Western cultures, it may also be likely that the apparent quality of student writing is not simply determined by their ability to think critically but is more fundamentally tied to the students’ own sense of motivation and belonging within the community that assesses their competence, as illustrated above, and as also described by Clark and Gieve (65) and Morita (583). At the very least, in an environment where an academic community continues to privilege Western scholarship and its associated approaches to thinking and writing critically, students from other cultures will continue to find it difficult to participate in these conventions. In this way, it is entirely possible that perhaps Pu’s insight is somewhat less culturally specific than she intended it to be.

That said, one of the many virtues of this book is that it is more focused on explaining what a cultural approach to critical thinking looks like than on detailing the potential implications of adopting this approach more broadly. In fact, it is because Pu rejects a universal assessment of students’ critical thinking ability that she is required to employ alternative approaches to assessing students’ critical thinking in her own conversations and evaluation of each student (123). Presumably, since Pu intended to propose a culturally specific approach, applying her analysis elsewhere will require relevant modifications that account for each student’s, tutor’s, or instructor’s own background as well as their local institutional context in future studies. Nonetheless, until these comparable studies can be completed in diverse contexts, it remains an open question whether or not Pu’s thesis has potentially broad cultural relevance, and indeed whether such results indicate a weakness or an advantage of her approach.

Notwithstanding these qualifications, Pu’s argument might be used to draw at least three related conclusions. First, student writing on its own is an insufficient metric of critical thinking ability and performance. Second, changing the way students write is fraught with important questions about individual positioning and cultural belonging rather than the considerably less important yet endlessly discussed questions about how to further expose every student to the existing Western, neo-colonial approach to critical thinking and writing instruction. Finally, students are more likely to share their critical thinking in this Western written form when they can understand and internalize the practical benefits and relevance of writing in this way to themselves and their own cultural practices, as shown above.

This is not to say, of course, that it is appropriate or desirable for all students to adopt a Western cultural approach in their writing and thinking, or that the explicit goal of all academic writing should be to demonstrate critical thinking as Western institutions and academics define it. At any rate, academic writing should not be the exclusive method by which instructors evaluate critical thinking. Instead, to return to questions introduced at the beginning of this review regarding the relevance of cultural differences to critical thinking instruction , one of the key insights from Pu’s study is that changing students to resemble a specific cultural environment may be misguided. Ultimately, our efforts might be better focused on creating a more inclusive environment that resembles and rewards the many ways students think critically.

Works Cited

Clark, Rose and S.N. Gieve. “On the Discursive Construction of ‘The Chinese Learner.’” Language, Culture, and Curriculum. vol. 19, no. 1, 2006, pp. 54-73. Taylor & Francis. https://doi.org/10.1080/07908310608668754

Dam, Geert ten and Monique Volman. “Critical Thinking as Citizenship Competence: Teaching Strategies.” Learning and Instruction. Vol. 14, 2004, pp. 359-371. ScienceDirect. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2004.01.005

Egege, Sandra and Salah Kutieleh. “Critical Thinking: Teaching Foreign Notions to Foreign Students.” Educational Research Conference, special issue of International Education Journal. vol. 4, no. 4, 2004, pp. 75-85. ERIC, https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ903810.pdf

Greasley, Pete and Andrea Cassidy. “When it Comes Round to Marking Assignments: How to Impress and How to Distress Lecturers.” Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education. Vol. 35, no. 2, 2010, pp. 173-189. Taylor and Francis. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602930802691564

Morita, Naoko. “Negotiating Participation and Identity in Second Language Academic Communities.” TESOL Quarterly. Vo. 38, no. 4, 2004, pp. 573-603. JSTOR. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/3588281.pdf

Tian, Jing and Graham David Low. “Critical Thinking and Chinese University Students: A Review of the Evidence.” Language, Culture, and Curriculum, 24, 1, 2011, pp. 61-76. Taylor and Francis. https://doi.org/10.1080/07908318.2010.546400