Praxis: A Writing Center Journal • Vol. 22, No. 3 (2025)

Reexamining “Attitudes of Resistance”: A Survey-based Investigation of Mandatory Writing Center Appointments

Chris Borntrager

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

clborntr@uark.edu

Taylor Weeks

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

tlw006@uark.edu

Abstract

This article arose out of a need to better understand what happens in university writing center (WC) appointments that are incentivized or mandated by instructors. While the topic has received attention in WC literature, previous research focuses largely on student attitudes toward mandated WC appointments and only rarely addresses the interpersonal dynamics of these sessions. To address this gap, we conducted an IRB-approved, survey-based study investigating the impact of WC tutorial incentivization on writing tutors’ assessments of sessions’ effectiveness, comparing tutors’ scoring of different session types and conducting statistical queries on some of the larger categories. Our results challenge the widespread assumption that mandatory or incentivized writing center sessions are always an obvious tradeoff of “quality vs. quantity.” Specifically, we found that differences in tutor scores between voluntary and mandatory WC sessions were statistically insignificant and did not present a clear tutor preference for voluntary sessions over mandatory sessions; however, when types of incentivization were compared, tutors showed a subtle preference for sessions that were incentivized through a class-wide mandate over those that offered extra credit or involved individual referrals. In this study, we also discuss common metrics for gauging writing tutorials’ success, suggesting that WC practitioners may be placing an undue weight on “engagement.” We hope, most of all, to encourage further research that examines (and expands) institutional approaches to mandatory sessions and encourages a more welcoming stance toward the writers who visit WCs at the behest of their instructors.

Introduction

Writing center (WC) practitioners have been discussing the merits, risks, and drawbacks of “mandatory” writing tutorials (i.e., visits to the WC that have been prompted, mandated, or incentivized by faculty) for decades. Even though peer review is an established and effective tool for teaching writing (Nielson), mandatory WC sessions have also garnered a reputation as a “necessary evil” because of the logistical problems they often present: they can fill up tutoring schedules suddenly and often entirely, which presents problems for administrative bandwidth and student relations; they may bring WC staff into contact with other university stakeholders who may not acknowledge them as curriculum-independent writing experts; and they may, because of an assumed lack of student engagement, deplete the emotional and intellectual resources of tutors more quickly than other session types. Even though they are heavily reliant on context, such obstacles as these have become associated over time with mandatory sessions even in the professional literature, often to the degree that practitioners approach them fatalistically and seem to expect less from them than from voluntary visits. As with any issue related to human beings and their literacy practices, however, those things which seem self-evident in professional circles are almost always more complicated than they seem—and often arise out of ideology. In presenting an empirical study of tutor assessments of mandatory sessions, we, along with such scholars as Jaclyn Wells, encourage WC professionals and those engaged in college teaching to interrogate their individual and collective beliefs about mandatory WC sessions, especially as these beliefs may affect practice. In this article, we argue that practitioners need to 1) question the tacit assumption that mandatory sessions are inevitably of poorer quality and 2) embrace a more open stance to writers who come at the behest of their instructors. For our (Chris’ and Taylor’s) part, our results remind us of something we often forget during an average day in the WC or writing classroom: far from being pre-determined, the writer-tutor dialogue—the core of the WC’s method—is dynamic, emergent, and full of possibility.

In this study, when we refer to WC sessions that are somehow incentivized by instructors, we use the phrase “faculty-incentivized writing center appointments” (FIWCAs). Hereafter, we use the acronym “FIWCA” to refer to WC appointments that meet any (or multiple) of the following criteria: 1) students are offered extra course credit for visiting the WC; 2) students are required to come to the WC as part of a class-wide general mandate; or 3) students are given an individual or specified referral to the WC. Gary Olsen notes that teachers often refer students to the WC in unique ways and with unique motivations, and we have tried to address this contextual complexity in our research design. These criteria, admittedly, do not cover the entire range of possibilities for incentivization of WC sessions, but they are, we think, useful for delineating some of the common referral practices that act as “bridges” between the classroom and the WC. The results of our study confirmed that, while some session types were indeed ranked lower or higher by tutors, the immediate context of a WC tutorial did not entirely determine its success rates or interpersonal dynamics; on the contrary, the instructional contexts that we measured seemed to have only limited impact on the scores tutors assigned to sessions. Based on our results, practitioners have ample reason to assume a multiplicity of possible outcomes for FIWCAs rather than approaching them fatalistically.

Previous Research on FIWCAs: Attitude and Engagement

Despite their ongoing image problem, FIWCAs are an accepted part of life for many writing centers. As such, most studies published on the subject address practical problems that these sessions present, focusing on such issues as faculty relations, student outreach, and administrative decisions. The practice has not been without its critics, however. Stephen M. North, in his well-known article “Idea of a Writing Center,” discourages teachers from referring students to the writing center no matter their intentions. He writes:

Even those of you who, out of genuine concern, bring students to the writing center, almost by the hand, to make sure we won’t hurt them—even you are essentially out of line. Occasionally we manage to convert such writers from people who have to see us to people who want to, but most often they either come as if for a kind of detention, or they drift away. (72)

In this passage, North’s indicates his key objection to FIWCAs: he seeks to preserve the student’s buy-in and general attitude (which, he implies, are themselves fundamental to the WC’s method) by protecting their sense of agency. Indeed, North grounds his vision of WC method in the motivation of the student writer, as evidenced by his use of the phrase “willing collaborator” (70) to describe the student’s role in an idealized session. Based on subsequent literature, professional attitudes toward FIWCAs seem to have softened over time, but certain key assumptions about their impact remain largely intact, including the impact of teachers’ referral methods (and even mannerisms) on student attitudes toward the session. Gary Olson, for example, found that students who had been referred to the writing center often arrived lacking motivation or confidence, something he attributes to teachers’ insensitive referral methods. Other researchers have likewise also focused on the ways that teachers’ practices influence WC sessions, with some having gone so far as to say that the teacher is “present” in writing center tutorials as an absent player (Rodby; Roswell; Servino; Waring). There have also been several articles that discuss FIWCAs more generally, investigating their overall efficacy and the attitudes of participants. Irene Lurkis Clark, who argues directly against the “old wisdom” by encouraging faculty to refer students to the writing center, problematizes any dichotomous thinking around the issue by noting that arguments against FIWCAs assume a homogeneous body of students and frequently rely on anecdote rather than research. Clark concludes that, because the students in the sample were unlikely to visit the WC of their own accord, it is ultimately in WCs’ favor for teachers to refer students, since FIWCAs are “perhaps better than no visits at all” (33). Wendy Bishop, reflecting on the difficulties of WC marketing initiatives, comes to similar conclusions, finding that many students in the study would not have come to the WC at all unless they were prompted by instructors. Barbara Bell and Robert Stutts, writing in The Writing Lab Newsletter, investigate both student and tutor attitudes in response to class-wide mandated sessions. Arguing that the benefits of FIWCAs outweigh the costs, they provide some useful strategies for ameliorating various attitudinal and logistical hurdles; however, when they note that the lack of student engagement in FIWCAs led to “angry students and exhausted tutors” (7) in their WC, they rely on anecdotal evidence. Barbara Gordon, in an article surveying research on FIWCAs, notes that WCs remain largely defensive against the practice even though research has largely refuted the negative impacts of these sessions. Jaclyn Wells, focusing on student attitudes on required tutoring, found that the students in her sample had a mixed response to FIWCAs but a generally positive attitude toward the WC more generally. Wells also goes a step further by reflecting on the defensiveness that Gordon points out, noting that WC research into FIWCAs is often not enough to cause WC practitioners to revisit their beliefs on the practice. In rhetorical pieces on FIWCAs (like North’s, for example) and practitioner pieces, authors appear free to rely on their experiences, whereas, in research articles, there is an apparent tension between “lore-bound” approaches to FIWCAs and more moderate, empirical approaches. The applied nature of WC work (and the apparent pragmatism of much of its professional discourse) means that there is ample guidance for administrators in such articles, but there is little attention given to empirical descriptions of FIWCAs in situ, the emphasis being on student attitudes toward the WC or teachers’ referral practices. As such, the tutoring and training implications of much previous research on FIWCAs are mostly implied rather than investigated directly.

There are a number of questions we can ask about previous research on FIWCAs as we take the conversation further. What is the relationship between the immediate context of a FIWCA and its interpersonal dynamics? Which parts of the context have been addressed in research and which have been implied? How are we judging a session’s “success,” and whose version of “success” is being privileged? What do tutors think of individual FIWCAs compared to non-FIWCAs? The student’s relationship with the teacher and their overall opinion of the WC, as mentioned above, are frequently considered key contextual factors in research, but, crucially, these are not connected explicitly to specific session outcomes. The success of a WC session, in empirical research on FIWCAs, is mediated almost exclusively through student attitude toward the WC, whether positive or negative. It is largely assumed, then, that a contextual element of a tutorial is relevant only as it pertains to a student’s buy-in, attitude, or stance; however, there is little evidence verifying the role that attitude plays in the interpersonal dynamics of actual tutorials. There is, in other words, a considerable conceptual gap between “student attitude” and a tutorial’s “success,” even though these are tacitly equated in much of the research on FIWCAs. On the surface, it indeed seems reasonable to assume that a negative student attitude will lead to poor session outcomes, but this assumption also underestimates the emergent, performative nature of attitude and the fluidity of the dyad. As Potter and Wetherell remark, attitude itself is not a static feature but is highly context-bound (45). A person’s attitude, whatever it may be at one moment, does not remain static across time and situations, nor does it perfectly predict future behaviors. If the success of a tutorial is measured solely by the writer’s attitude at a particular moment, then researchers risk reducing the tutoring session to a mechanistic exchange that is at the mercy of the preconceived notions of either party, rather than viewing it as a dialogue that is context-bound and discursively negotiated. Pedagogically speaking, a student writer’s positive attitude should not be taken as a de facto success.

In addition to its exclusive emphasis on student attitude, previous research on FIWCAs also studies them in isolation from their communicative contexts and, crucially, without comparing them to non-FIWCAs—that is, they are studied apart from the time, place, and interpersonal dynamics of the tutoring session, and any difference between FIWCAs and non-FIWCAs is not empirically verified. It remains largely to be investigated which aspects of a tutorial’s context most readily impact its interpersonal dynamics. It has already been established that teachers exercise profound influence on the dynamics and outcomes of writing center sessions (Callaway; Jordan); our research, in its turn, compares tutor assessments of both FIWCAs and non-FIWCAs, thereby exploring the ways that teachers’ common referral methods affect the quality of writer-tutor dialogue across a larger sample. The overall conversation surrounding teacher referrals to the WC can benefit, we think, from 1) more empirical research, 2) clarification of FIWCAs’ impact on the dynamics of individual sessions, and especially 3) the inclusion of writing tutors’ perspectives on the issue.

Methodology

In this section, we describe the research site, the instruments we used, the process of data gathering, and some of the limitations of our study. Over the course of the project, we gathered data on 88 WC tutorials, using a total of 176 data points to investigate connections between external contexts and the interpersonal dynamics of the session. Using paired surveys to collect data from both student writers and tutor, we were able to form “snapshots” of tutors’ ratings of specific referral types and compare FIWCAs to non-FIWCAs statistically; however, our sample size—taken as it was from a single university in the heartland of the United States on the cusp of COVID lockdowns—is too small to reliably generalize our findings and apply them to other settings and times. As such, we understand our findings to be exploratory descriptions of the WC tutoring sessions as they appeared in a specific time and place. Furthermore, questions related to literacy, which Brian Street defines as “social practices of reading and writing” (111), are inextricably bound up in complex social processes and situated meanings; as such, literacy practices are most productively explored through a variety of approaches, especially through qualitative means that account for cultural and social influences. One more empirical study on FIWCAs will not settle the issue, but it may yet add weight to ongoing critiques and reexaminations of WC practice.

During the time that we gathered data for this project, we (Chris and Taylor) worked, consecutively, as graduate assistants in a writing center which served a student body of about 26,000 and maintained a staff of 11 writing tutors (four graduate and seven undergraduate). In our roles as graduate assistants, we oversaw tutor training, scheduling, professional development, and outreach. After gaining IRB approval (approval # 1810153663) in the fall of 2019, we began administering in-person, written surveys to student writers and their tutors, continuing until the middle of the spring term of 2020, when the COVID pandemic effectually ended face-to-face instruction at our university, whereupon we decided to move ahead with a smaller sample size. Neither tutors nor students were incentivized to complete their surveys, though we suspect that our positions of authority in the WC may have pressured tutors to contribute to the project. During the data gathering phase, each tutoring station was supplied with pens, written surveys, and detailed scripts that familiarized tutors with the project and provided disclaimers about voluntary involvement in the project. If the student agreed to participate, they completed the entrance survey before the tutorial began; then, after the tutorial had concluded, the tutor would complete the corresponding exit survey for that specific tutorial. If the student declined to participate, then the tutor was instructed not to fill out an exit survey. Once a student and tutor had both completed their surveys, the tutors were instructed to staple the two surveys together and place them in a large manila envelope that we had provided for that purpose. At the end of each tutor’s shift, one of the researchers collected the envelopes, placed a new manila envelope at the tutoring station, and deposited the completed surveys in a secure lockbox. Both the entrance and exit surveys asked respondents to enter the date and time of the tutorial, and we used these dates and times to match any surveys that tutors had neglected to staple together. If we could not find a match for either an entrance or exit survey, we omitted them from our data set. Once data gathering was completed, we entered our results into Microsoft Excel and destroyed the paper copies afterward.

The entrance surveys, intended for student writers, asked respondents to rate their understanding of the assignment and their self-confidence as they entered the session. We also asked students to circle either “Yes” or “No” in response to the following questions:

Were you required by your instructor to visit the writing center?

Were you offered extra credit for visiting the writing center?

Did you receive any special instructions from your instructor regarding your visit to the writing center? (i.e., were you asked to focus on a specific area of the paper or specific skill?)

If “yes” to above question, please list the area(s) you were asked to work on. (A space was provided on the survey to allow for short answer comments.)

In this survey, we sought to distinguish between these different contextual aspects of the sessions. The third question, for example, indicates an individual referral, which Olson suggests can have a deleterious effect on student motivation. The contextual data gathered in the entrance survey was then paired with their corresponding tutor scores, such that the sessions could be grouped and rated according to their provenance. The exit survey, designed for tutors, used a 1-5 scale (1 = “not at all,” 5 = “very”) to answer the following 5 questions:

Overall, how well do you think the session went?

How easy was it to establish rapport with the writer?

How engaged did you sense the student was in the session?

How committed did the writer seem to making further changes?

How impactful were the changes that the writer made to the paper?

Since we were interested in the tutors’ perspectives on the interactional dynamics of the sessions, we did not elaborate on the meaning of the different questions, preferring to trust the tutors’ notional understandings of the terms. For example, we did not provide any coaching in the various ways that a person may express engagement in a dyad (i.e., turn length, eye-contact, body language, prosody, or positing new topics), but instead allowed the tutor to answer according to their felt sense of a writer’s engagement or commitment without having to defend or quantify their assessment. We were more interested in tutors’ impressions of the session than in the sessions’ minutia or in any specific discursive move, as we did not account for social or cultural factors in communication in our surveys.

We conducted our analysis in two phases: we compared mean tutor scores across different session types (which makes up the bulk of the discussion below) and performed a statistical analysis comparing tutors’ scores of FIWCAs to those of non-FIWCAs. For the comparison of mean scores, we grouped our data to create cursory “snapshots” of tutor assessments for different types of sessions, including those sessions that were incentivized through extra credit or which involved a class-wide mandate. For the statistical test, we used RStudio to conduct a Mann-Whitney test to determine any statistical significance between the tutors’ scores of FIWCAs and those of non-FIWCAs.

This study has two main limitations that we have identified: relatively small sample sizes and a lack of demographic data. The first of these means that our findings would need additional verification in various times, places, and cultural contexts to gain anything more than a highly situated validity. The second means that our choice of instrument, a paired survey, does not gather much information on contexts outside of the classroom or the WC, so the meanings we can make of our results are necessarily limited. We did not account, for example, for such factors as race, language backgrounds, gender identities, or socioeconomic backgrounds, all of which exercise profound effects on access to educational opportunities and other social goods. We acknowledge that this quantitative study can give only a limited picture of irreducibly complex realities. As such, we view our findings as a single part of a much larger picture—we take them to be merely exploratory, a prompt to reexamine aspects of WC practice and professional discourse. Indeed, Carino and Enders remark that, while quantitative studies may not be the best choice of research methodology for “mapping complex realities,” they are especially useful for challenging and elaborating the lore—the “dark knowledge”—that exists tacitly in communities of practice (84). This latter point is chief among our aims in this article.

Results

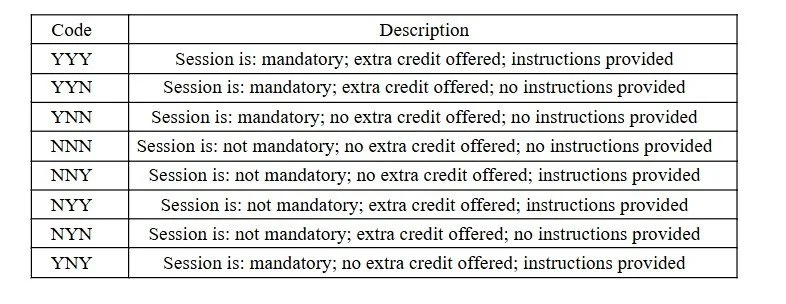

First, to differentiate the different contexts of the sessions, we created a series of codes indicating what type of incentivization, if any, was attached to each WC appointment in our data. These codes are described in the table below.

Table 1. Explanation of session codes. Every profile except for “NNN” qualifies for the category of FIWCA, which means that “NNN” is synonymous with “non-FIWCA” in that students in this category came to the WC of their own choice and were not incentivized to visit.

When creating these codes, we isolated the three variables in the students’ entrance surveys that established some of the context surrounding the students’ visits, including: whether the session was mandatory (in that it was a class-wide mandate built into the structure of the class); whether extra credit was offered to incentivize the visit; and whether the teacher had provided specific instructions that the student was to follow, this being taken as an indication of an individual referral. We used these codes to correlate the students’ entrance surveys with the tutors’ exit surveys and establish the mean scores of each code for purposes of comparison. Tutors’ scores, when we provide them, are rounded to the nearest hundredth.

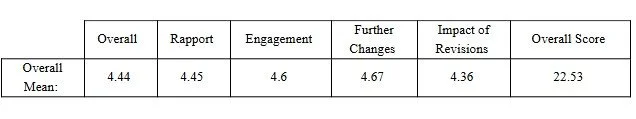

Overall average scores were as follows:

Table 2. Overall averages for the entire data set, which includes both FIWCAs and non-FIWCAs.

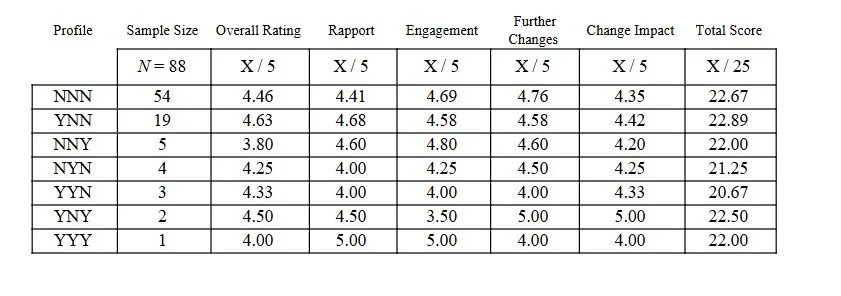

In the table below, we include the totals of each session type along with their mean scores.

Table 3. Mean scores of each session profile, arranged in order of most responses (top) to least (bottom), including mean total scores. From left to right, we provide: a list of session profiles in descending order of size; the total number of each session type present in our data; the mean scores of tutors’ overall assessment of the session; the mean scores of tutors’ assessment of student rapport; the mean scores of student engagement in the session; mean scores of students’ apparent commitment to making further changes in the draft; mean scores of the impact and effectiveness of changes made in the student’s draft; and the mean total score of each session type. There were 5 points possible in the first 5 categories; 25 points were possible in “mean total score.”

Out of 88 sessions (and 176 different data points), only 34 sessions qualified as FIWCAs; the remaining 54 sessions were all student-initiated. This meant that, since we were applying the same metrics to both FIWCAs and non-FIWCAs, we could compare their overall scores and see if various kinds of incentivization had any apparent impact on the tutors’ scores (this we do in a later query).

After this first exploratory query, we were struck by the variability of contexts and lack of a clear “winner” in tutor scores, both of which suggest that the sessions’ contexts did not influence tutors’ assessments in any obvious or overwhelming way. If the widespread assumptions about FIWCAs were accurate (i.e., that FIWCAs tend to have lackluster interpersonal dynamics), we might have expected the category “NNN” to score higher in every area, but this is true only in the “commitment to further changes” category. For every other metric of success, one or another FIWCA takes the lead: “YNN,” the second-largest code overall and largest category of FIWCA, has the highest total score (22.89 out of 25) as well as the highest score in rapport; “NNY,” the third-largest category, has the highest mean rating in overall engagement (0.11 points above “NNN” and 0.22 points above “YNN”) but the lowest rating in “overall score.” This was our first indication that the commonsense understandings of FIWCAs might not hold up on closer inspection.

In addition to the relative uniformity of tutors’ scores across categories, we also found that measures of engagement and rapport were viewed separately from tutors’ overall views of a session’s success; in fact, tutors favored “YNN,” a FIWCA, in both “total score” and “overall score” despite "YNN” having an “engagement” rating that was lower than non-FIWCAs by 0.11 points. This was our first indication that our tutors were assessing “engagement” as an independent factor separate from their sense of the sessions’ overall success, since lower engagement did not seem to lead to lower tutor scores overall or a lower total score.

Once we had compiled our data according to session code, we conducted more targeted queries that investigated in finer detail the impact of referral methods on sessions’ interpersonal dynamics. We asked: “how do FIWCAs compare to non-FIWCAs in tutor assessments?” and “how were different types of FIWCAs rated by tutors?”

FIWCAs vs. Non-FIWCAs: How do they compare?

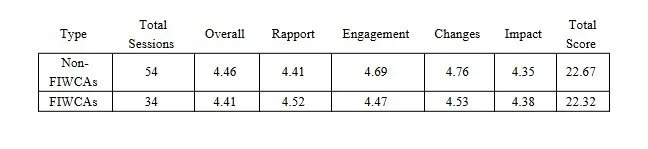

In addition to testing the usefulness of our session codes, we were especially interested to see how FIWCAs writ large compared to non-FIWCAs in our tutors’ assessments. Indeed, among our various questions related to WC practice, this seemed to be the most pressing, since the two categories had not been compared using the same metrics (that we were aware of). For this query, we aggregated the 34 FIWCAs (that is, we aggregated all codes except “NNN”) and compared them against the 54 non-FIWCAs, examining the mean scores of the accompanying exit surveys and conducting a statistical query on the two groups. When we looked at our “snapshot” of the mean tutor scores, the results seemed to support some of the previously discussed “commonsense” understandings of FIWCAs, but we suspected that aggregating FIWCAs elided differences between FIWCA categories that are apparent only when the session codes are separated. Combining the FIWCAs, in other words, brought their scores down across the various metrics, even though, as we had already established, not all FIWCAs were equally deleterious to tutors’ assessment of their success.

Table 4. Average scores of FIWCAs vs. Non-FIWCAs.

In the previous query, “YNN” (the largest category of FIWCA) had a sizeable lead over “NNN” (non-FIWCAS) both in total scores and in “overall” assessment, while “NNN” held a noticeable lead in “engagement.” When FIWCAs (aggregated) are compared with non-FIWCAs, however, the latter takes a substantial lead in total scores, “engagement,” and “willingness to make further changes,” while attaining only a modest lead in “overall rating.” FIWCAs held small leads in the categories of “rapport” and “impact of changes made.” This apparent reversal from the previous query is a reminder that many of the less common FIWCA profiles (especially those that involved extra credit or individual referrals) received lower scores from tutors. FIWCAs writ large, as a result, were not rated as well as non-FIWCAs in most areas.

In addition to forming a “snapshot” of the tutors’ assessments of FIWCAs vs non-FIWCAs, we also investigated whether there were any statistically significant differences in the scores between these two categories. To this end, we conducted a Mann-Whitney query on our survey data. We imported our cleaned data file into RStudio, grouping FIWCAs and non-FIWCAs so that the individual scores of each session in the dataset could be compared. Having used ggplot (a data visualization tool) to determine that our dataset was sufficiently “skewed’ (i.e., not a normal, bell-shaped distribution), we compared each set of session scores against that of the other group for a total of six separate queries. For example, the first query compared FIWCA’s “engagement” scores with the “engagement” scores of the non-FIWCAs and determined whether they were significantly higher or lower. When we gathered the results of our six different queries, the p-value of each comparison was well below the traditional threshold for statistical significance, 0.05. This meant that there was no statistically significant difference between the scores of FIWCAs and non-FIWCAs in any category. See the table below for a breakdown of each category.

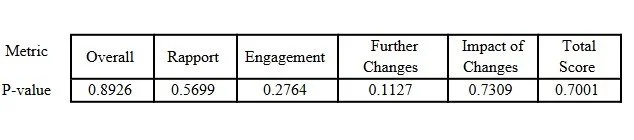

Table 5. Results of the Mann-Whitney query.

The first group, non-FIWCAs, was compared with the second group, FIWCAs, in each category, “Overall,” “Rapport,” etc., and the p-value was noted to determine whether or not one category was significantly higher or lower. The p-value of each category was notably higher than 0.05, signaling that no statistically significant difference exists between the FIWCAs and non-FIWCAs in our sampling.

Aggregated FIWCA Profiles: How do FIWCAs compare against each other?

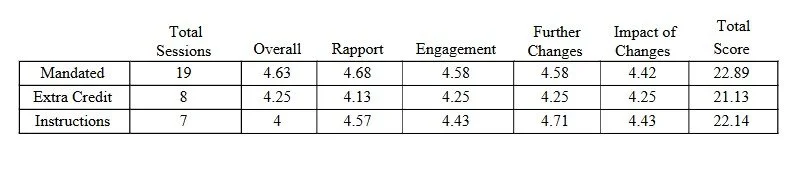

Finally, to get a clearer picture of the differences between the three referral methods (mandatory, extra credit, specific instructions), we aggregated the different variables so that we had only three profiles of FIWCAs overall, one to represent each of the incentivization types represented in our data; we then compared the mean tutor scores of each category (we deemed the resultant groups too small to conduct statistical queries). To create the category “mandated,” we used the code “YNN”; for “extra credit,” we aggregated “YYY,” “NYN,” and “YYN”; and for “instructions,” we aggregated the codes “NNY” and “YNY.”

Table 6. FIWCA profiles aggregated according to the three variables: extra credit offered, visit mandated, and specific instructions offered.

“Mandated” was the clear winner among the three aggregated FIWCA categories. It had a large lead, up to 0.75 points, in “total score” and had a sizeable lead in “engagement,” “rapport,” and “overall rating.” “Extra credit,” the second largest category, came last in every category except “overall rating,” a full 0.38 points behind “Mandated”; in fact, the spread between “extra credit” and the other FIWCA categories is so large that it merits special attention. Whereas the “instructions” category performed well in all categories when compared against the overall average, “extra credit” came in at an average of 0.30 points behind the overall mean scores. “Instructions,” shorthand for “individual referrals,” performed better, coming in second place in all categories except “overall rating,” which is full 0.44 points below the average.

Discussion

The sessions in our dataset are localized in a culture, a location, and a particular historical moment, which means their results cannot reasonably be applied to other university writing centers or student bodies without caveat. Based on the results of our study, however, we can safely say this: WC practitioners (and those who take an interest in WC work) would do well to challenge any deterministic views of FIWCAs that would automatically assume them to be of poorer quality than non-FIWCAs. While some types of FIWCAs in our data (especially those that indicated extra-credit incentivization) did indeed receive notably lower ratings than non-FIWCAs, one particular type of FIWCA, the “mandatory” session, outperformed non-FIWCAs in several areas. The results of the Mann-Whitney query, furthermore, confirmed what we had initially suspected: that there were also no statistically significant relationships between FIWCAs and non-FIWCAs.

We also found that not all FIWCAs were rated equally by tutors, nor were they equally detrimental to a session’s dynamic. Indeed, even though non-FIWCAs (“NNN”) are deemed “best-case-scenarios" by many WC practitioners, “mandatory” (“YNN”) outperformed them in most regards except for engagement, including in areas pertaining to tutors’ “overall” assessments of the session. “YNN” also scored notably higher than other types of FIWCAs in the first query, and “Mandatory Aggregated” (“YNN’s” counterpart in the comparison of FIWCA types) was the overall leader among FIWCA types when these were compared against each other. This is an indication that simply comparing FIWCAs to non-FIWCAs is not necessarily an effective comparison if we are interested in improving tutoring practice—they need to be differentiated with reference to the types of incentivization. In other words, since not all types of mandatory sessions had the same impact on engagement or tutor scores, it is worthwhile for practitioners and researchers to make distinctions between the types of sending and incentivization rather than to treat FIWCAs as a single category with a single supposed outcome. The sheer variability of referral methods in our data and the relative uniformity of tutor scores suggest that the current scholarly conceptualization of WC session contexts needs to allow for more complexity than simply “required vs not-required.” Having affirmed Irene Lurkis Clark’s remark that student bodies are not monolithic, we suggest that practitioners should assume a multiplicity of situations when considering the contexts that might affect the quality of the writer-tutor dyad.

We also discovered that “engagement” was not an effective predictor of a tutor’s rating of a session’s overall success. “YNN,” a type of FIWCA, received notably higher overall ratings than non-FIWCAs despite the former receiving lower scores in engagement and rapport. In other words, although it was correct that student engagement and rapport tended to be lower in FIWCAs, the other aspects of the session, including the tutors’ overall impressions of the session, did not suffer thereby, which suggests that tutors were not treating engagement as the only factor leading to a session’s success. When other metrics were applied to the session, including the writer’s commitment to making further changes and the effectiveness of the changes made, tutors indicated that meaningful work was still being done in their sessions despite their lower assessment of student engagement. This is indeed good news for writers and tutors, especially since shows of “engagement” in a dyad are culturally situated behaviors that have no “final form”; these results reaffirm the need to approach conceptions of engagement critically and with reference to power differentials between interactants. We do not mean to say that engagement is not important in a WC session—we only mean to say that engagement is only one of many considerations in a WC session and, perhaps, ought not be overemphasized at the expense of other goals, for reasons which we discuss in the next section.

Conclusion: Examining WC Views of Writer Engagement

As Jaclyn Wells writes, it is easy to ignore uncomfortable research findings, but, all the same, WC practitioners need to discover “what ideals hold us back from implementing new findings and make us cling to old approaches to writing center work” (108). In keeping with this suggestion, we here address some possible ideological underpinnings of professional discourse on FIWCAs. We have come to suspect the reason FIWCAs rankle us has more to do with our aversion to student recalcitrance than it does to matters of faculty relations. Indeed, we wonder whether or not FIWCAs are really just a convenient scapegoat for a deep mistrust of student disengagement.

Like any other discipline, WC practitioners have their own ideologies arising out of their particular histories and contexts of practice. The field seems to have developed its own unique understanding of “dialogue” to such an extent that, rather than creating bridges for student writers, this conception can present interactional difficulties for those who do not share our conventions, expectations, or rules of engagement. If the WC’s method is based in dialoguing with writers, then a dialogue must—so goes the accepted logic—be a “two-way street,” with both parties contributing to a new and better state of knowledge. But the reality is more complex. The “rules” of dialogue are intersubjective, endlessly variable, and culturally-situated, which means that, if WC practitioners hold too strongly to a particular conception of participation or engagement, they also risk reifying an entire constellation of values, behaviors, words, and discourse practices which a good many—millions, in fact—of our students do not share. “Recalcitrance” does not take one form any more than “engagement” takes one form. If WC practitioners are really committed to an inclusive WC practice, we need to revisit our attachment not only to student agency (as evidenced by the ongoing conversation about FIWCAs) but also to student “engagement.” By continuing to idealize a narrow conception of dialogue, we can very easily assume that a recalcitrant writer is an obstacle to our method rather than the very object of our method.

In The Bedford Guide for Writing Tutors by Leigh Ryan and Lisa Zimmerelli, the authors include a “challenging situations” section, something that we have seen in multiple other tutoring guides. Here, they refer directly to FIWCAs when giving guidelines regarding recalcitrant writers, offering it as a possible reason why a session may seem to lack student buy-in. They write:

Teachers sometimes require students to visit the writing center, and occasionally, such writers come with an attitude of resistance. They may refuse to answer your questions, give halfhearted answers, or otherwise indicate that they do not want to be there. Often, their body language is telling. They may slump in their seats, avoid eye contact, or avoid facing you. How do you help these writers? (104)

The authors then provide a list of “dos” and “don’ts, including reminding the writer of their ability to accept or reject the tutor’s comments, cutting the session short, bringing the writer into the dialogue by giving them prompts or activities, or hoping that the writer may return another day when their attitude has improved. There is, notably, no mention of how to proceed with the session if the writer does not change their behavior—the emphasis remains on how to remove the obstacle so business can proceed as normal.

In this above excerpt, it is especially notable how the recalcitrant student is approached in relation to the authors’ conception of the WC’s method: the attempts to establish buy-in and offer both parties a means of dignified escape place the writer in a sort of “waiting area” outside of genuine dialogue, where the “real work” will get done. The problem the authors point out is not so much that the writer might have been commanded to come to the WC, but rather that they are not engaging with the tutor and are resisting the tutor’s objectives. A close look at this passage, we think, suggests that our issues with FIWCAs are really issues with perceived writer recalcitrance.

The above excerpt is, all in all, a good piece of advice for writing tutors, but it is also an example of the ways our ongoing attachment to writer engagement can limit our conceptions of possibilities in writing tutorials. As we have established in this study, not only did several types of FIWCAs perform similarly to non-FIWCAs, but tutor assessment of a session's success was largely independent of the students’ shows of engagement. The potential harm that we see in an overemphasis on engagement is not so much that our attitudes toward FIWCAs may be unduly sour but rather that it may lead us to sell short the possibilities of a session based solely on what we know about that session’s immediate context. As theorists in discourse studies (refer, especially, to John Gumperz) have established, context is a process more than a set of concrete circumstances, and as such is co-constructed and malleable. Gary Olsen confirms this by noting how negative student attitudes often seem to change during the course of the session, often in response to the tutor’s demeanor and professionalism. The tutor, in other words, has more chances to work with and through writer resistance than tutoring guides seem to suggest. If WC practitioners perceive “writer recalcitrance” merely as an obstacle to the learning process rather than a step in the learning process, there may be no one else who will see it as a learning opportunity for tutors and writers—without direct and meaningful intervention, recalcitrance may indeed alienate students from the WC and perhaps from writing (as a skill and a subject).

Ultimately, we do not need to address our discourse about FIWCAs and recalcitrant writers just because there is sufficient evidence to contradict them; we need to change our discourse about them because our ways of speaking and writing about them finds its way, like groundwater, into tutoring practice—through training sessions, instructional texts, and the formation of lore. We would do well to address our attachment to writer agency because our discursive practices affect the lived realities of those whose work and schooling we are responsible for. Since our tutors and writing fellows are the ones who enact any method WCs may be said to have, we ought to equip our tutors to welcome writer recalcitrance with poise, not to encourage them to enter “damage control” mode as soon as a writer slumps in a chair.

Call for Further Research

The results of our study do not represent a comprehensive investigation of FIWCAs writ large, but merely a small sample from a single university writing center in the continental United States. As such, we would hope that researchers, administrators, and practitioners across the world would make their own attempts to study the phenomenon in question. All we can safely say, based on our results, is that FIWCAs do not lead to poor session quality every time.

Additionally, there is a need for new training material and research focusing on serving students who have difficulty, for any number of reasons, joining in a dialogue about their writing. On the one hand, exploring mindfulness techniques may allow tutors to find common ground with reticent or recalcitrant writers. Tutors may also benefit from more research that uses interactionally-based research methodologies to account for the ways that individuals negotiate their aims, contexts, and expectations in tutor-writer conversations (i.e., conversational analysis via Harvey Sacks, ethnography of communication via Dell Hymes, and frame analysis via Erving Goffman, to name a few). Mackiewicz and Thompson, for example, use discourse analysis to establish key discursive moves made by experienced writing tutors. Such methodologies may enable us to, for example, further critique dominant conceptions of “engagement” or “recalcitrance” and enact more insightful critiques of tutoring practice, especially of the ways that whiteness and unequal power relations are baked into common understandings of “rapport” and “engagement.”

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Henrietta Tettey-Tawiah at SMSS for their help with the Mann-Whitney query. The authors state that there was no conflict of interest. All research was carried out in compliance with our institution’s IRB board. The authors did not use generative AI for any writing or research aims associated with this project.

References

Bell, Barbara and Robert Stutts. “The Road to Hell is Paved with Good Intentions: The Effects of Mandatory Writing Center Visits on Student and Tutor Attitudes.” The Writing Lab Newsletter, vol. 22, no. 1, pp 5-8, https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/wln/v22/22.2.pdf

Bishop, Wendy. “Bringing Writers to the Center: Some Survey Results, Surmises, and Suggestions.” The Writing Center Journal, vol. 10, no. 2, 1990, pp. 31–44, https://doi.org/10.7771/2832-9414.1194.

Callaway, Susan J. Collaboration, Resistance, and the Authority of the Student Writer: A Case Study of Peer Tutoring. (Volumes I and II). 1993. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses.

Carino, Peter, and Doug Enders. “Does Frequency of Visits to the Writing Center Increase Student Satisfaction? A Statistical Correlation Study—or Story.” The Writing Center Journal, vol. 22, no. 1, 2001, pp. 83–103, https://doi.org/10.7771/2832-9414.1492.

Clark, Irene Lurkis. “Leading the Horse: The Writing Center and Required Visits.” The Writing Center Journal, vol. 5/6, no. 2/1, 1985, pp. 31–34, https://doi.org/10.7771/2832-9414.1912.

Gordon, Barbara Lynn. “Requiring First-Year Writing Classes to Visit the Writing Center: Bad Attitudes or Positive Results?” Teaching English in the Two-Year College, vol. 36, no. 2, 2008, pp. 154–63, https://doi.org/10.58680/tetyc20086887.

Gumperz, John J., et al. “Interactional Sociolinguistics: A Personal Perspective.” The Handbook of Discourse Analysis, Blackwell Publishers Ltd, 2005, pp. 215–28, https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470753460.ch12.

Jordan, Kerri Stanley. Power and Empowerment in Writing Center Conferences. 2003. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses.

Mackiewicz, Jo, and Isabelle Kramer Thompson. Talk about Writing : The Tutoring Strategies of Experienced Writing Center Tutors. Routledge, 2015.

Nielsen, Kristen. “Peer and Self-Assessment Practices for Writing across the Curriculum: Learner-Differentiated Effects on Writing Achievement.” Educational Review (Birmingham), vol. 73, no. 6, 2021, pp. 753–74, https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2019.1695104.

North, Stephen M. “The Idea of a Writing Center.” College English, vol. 46, no. 5, 1984, pp. 433–46, https://doi.org/10.2307/377047.

Olson, Gary. “The Problem of Attitudes in Writing Center Relationships.” Writing Centers: Theory and Administration, editied by Gary Olson. National Council of Teachers of English, 1984, pp. 155–169.

Potter, Jonathan, and Margaret Wetherell. Discourse and Social Psychology: Beyond Attitudes and Behaviour. Sage Publications, 1987.

Rodby, Judith, et al. “The Subject Is Literacy: General Education and the Dialectics of Power and Resistance in the Writing Center.” Writing Center Research, 1st ed., Routledge, 2002, pp. 221–34, https://doi.org/10.4324/9781410604026-16.

Roswell, Barbara Sherr. The Tutor’s Audience Is Always a Fiction: The Construction of Authority in Writing Center Conferences. 1992. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses.

Ryan, Leigh, and Lisa Zimmerelli. The Bedford Guide for Writing Tutors. Sixth edition, Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2016.

Street, Brian. Social Literacies: Critical Approaches to Literacy in Development, Ethnography and Education. Longman Group Limited, 1995,

Severino, Carol. “Rhetorically Analyzing Collaboration(s).” Writing Center Journal, vol. 13, no. 1, 1992, pp. 53–64, https://doi.org/10.7771/2832-9414.1288.

Waring, HM. “Peer Tutoring in a Graduate Writing Centre: Identity, Expertise, and Advice Resisting.” Applied Linguistics, vol. 26, no. 2, 2005, pp. 141–68, https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amh041.

Wells, Jaclyn. “Why We Resist ‘Leading the Horse’: Required Tutoring, RAD Research, and Our Writing Center Ideals.” Writing Center Journal, vol. 35, no. 2, 2016, pp. 87–114, https://doi.org/10.7771/2832-9414.1802.