Praxis: A Writing Center Journal • Vol. 22, No. 2 (2025)

Accidental Power: A Critical Discourse Analysis of Writing Center Interactions Between Tutors and Multilingual Tutees

Lisa DiMaio

Drexel University

dimaiola@drexel.edu

Abstract

My intent in this qualitative study was to illustrate if and how inequalities in power and authority exist in interactions between tutors and multilingual (ML) tutees set in a university writing center in a predominantly White institution (PWI). Using Fairclough’s model of critical discourse analysis (CDA) as a guide, I analyzed selected transcripts to uncover how “language shapes and positions” tutors and tutees (Fernsten 45). I propose that using CDA to examine writing center transcripts can be an effective training tool for tutors working with multilingual writers. By analyzing how their discourse choices may unintentionally bolster linguistic dominance and diminish ML students’ voices, tutors can adapt their approaches while also identifying discourse choices that lead to constructive, collaborative interactions.

Writing centers are often seen as safe spaces where tutors and tutees collaborate and cooperate. However, a hierarchical relationship, exemplified by dominance, power, and control, often exists between tutors and multilingual tutees, whether inadvertently or not (Akhmad; Chang; Thonus; Williams). Controlling a tutorial deprives ML writers of using their unique voices and inhibits language development (Williams). In this study, I illustrate how inequalities in power and authority exist in interactions between native-speaking (NS) tutors and ML tutees set in a predominantly White university writing center. Using Fairclough’s model of critical discourse analysis as a methodology, I analyzed selected transcripts to uncover how “language shapes and positions” (Fernsten 45) tutors and tutees. My analysis revealed the power dynamics between NS tutors and ML tutees and illustrated how tutors inadvertently bolster social dominance around proper language. I argue that applying CDA to writing center transcriptions as a method of training can assist tutors when working with ML tutees: by learning from the transcriptions and analysis that their discourse choices might reinforce language hegemony, stripping their ML students of their voice and identity, tutors can improve and modify their strategies. Conversely, tutors can identify discourse choices that lead to constructive, collaborative interactions. In the next sections, I review research on ML writers in the writing center, explain this study’s methods, and present the results of the CDA, concluding with recommendations for tutor training. The study was IRB-approved.

A New Path Forward for Tutors and ML Tutees

When ML writers, with their varied cultures and languages, go to the writing center, tutors might regard their linguistic differences as weaknesses; the diversity these writers bring might not be positive, especially in a predominantly white institution. Dees, Godbee, and Izias advocate caution regarding diversity in the writing center: “Differences are more than just differences; they become unfair organizers of our lives, providing some of us with fewer opportunities, less insider knowledge, and limited access” (1). When tutors allow differences to define students and their interactions with them, then they are essentially allowing differences to divide them.

In their article, “Building a House for Linguistic Diversity,” Condon and Olson addressed how tutors focus on difference. They questioned what the relationship is “among language, intellectual ability, individual value, and national belonging” (37). They said that tutors must be cognizant of the perceptions “regarding language and difference” (41). While tutors need to acknowledge that differences do exist in their ML students’ writing, they need to create equitable conditions to promote learning.

To negotiate difference effectively, Canagarajah, in “Multilingual Writers,” suggests that “in place of this ‘limiting’ stance, we move toward a ‘difference-as-resource’ stance, in which we respect and value the linguistic and cultural peculiarities our students may display, rather than suppressing them” (Canagarajah 210). This approach reframes ML students’ writing as a strength rather than a deficiency. Canagarajah further argues that exclusive focus on “standard” English inhibits the “linguistic acquisition, creativity, and production among students” (“World Englishes” 592), recognizing differences as deficiencies. On the contrary, accepting differences is valuing the student’s identity and voice.

Asao Inoue, in “Afterword: Narratives That Determine Writers and Social Justice in Writing Center Work,” highlights how institutions create and uphold “singular linguistic standards that writing centers are expected to promote” (96). Committed to equity and social justice, Inoue argues that writing center work must focus on challenging racism and white privilege, which marginalizes students from diverse backgrounds. Inoue encourages moving beyond linguistic hierarchies that privilege certain ways of speaking and writing; embracing linguistic diversity, he asserts, creates a foundation of equity.

Matsuda and Cox warn that a potential goal of tutors to make ML writing identical to native English writing — an assimilationist goal (Leki) — leads to the “imposition of the norms of the dominant U.S. academic discourse as well as the cultural values that come with it” (9). Matsuda asserts that multilingual writers bring distinctive issues to writing centers; consequently, he recommends that we “reexamine some of the fundamental assumptions of the writing center, which were developed with monolingual English users in mind” (“Teaching Composition” 47). Rather than expecting ML writers to achieve native-like proficiency, tutors must recognize that ML writers will often possess traces of their own linguistic backgrounds (Bruce and Rafoth; Leki; Matsuda and Cox; Severino and Deifell). Collier and Mitchell, Destino and Karam claimed that it could take ten years for ML students to become proficient in academic English, and in 2001, the Conference on College Composition and Communication [CCCC] Statement on Second-Language Writing and Writers asserted the same. Achieving native-like proficiency for ML students is quite rare; they are likely to reach a certain level and not acquire language past that point (Ritter). Writing centers need to recognize this reality and support ML writers in developing their own voices—ones that do not need to conform to dominant language ideologies.

In my study, I investigated how tutors and tutees negotiate differences (i.e., treat errors) and how tutors might assert power and privilege. I used critical discourse analysis as a methodology in examining transcripts of tutoring sessions. Van Dijk mentions that CDA is a “type of discourse analysis research that primarily studies the way social power, abuse, dominance, and inequality are enacted, reproduced, and resisted by text and talk in social and political contexts” (352). In a previous study, Fernsten investigated issues related to multilingual students and talked about how CDA could be used in research with ML students. She claims CDA reveals how language situates individuals within society and how discourse choices are influenced by various norms. She mentions that CDA can be used to “raise awareness of language in its social context and can also help people understand and control their own roles in the use of discourse” (Fernsten 46). Applying CDA to transcriptions offers opportunities for professional development.

Based on the current research regarding language diversity and ML writers in the writing center and the results of my study, I suggest a new path forward as we reevaluate tutoring methodologies to create equitable sessions for ML writers whose voices are often corrected and replaced. Implementing CDA as a tutor training methodology will provide tutors invaluable opportunities to gain meaningful insights into discourse choices that shape equitable writing center interactions and those that stifle them.

Methodology

Setting

The setting for this study was the writing center within a predominantly White public research university in a suburb west of Philadelphia. The total student population at this university at the time of this study was 17,005 but had 118 international students on F-1/J-1 visas from more than 40 countries, according to the Office of the President. Seventy-six-point five percent of the undergraduates were White (College Factual); this fits the definition of a predominantly White institution. The international enrollment at this university was 0.7% (College Factual). The international student body consisted of the following countries and number of students from those countries:

20 from India

16 from China

10 from Nigeria, Saudi Arabia

7 from Norway

6 from South Korea

5 from Hong Kong

3 from Ireland, Venezuela, Vietnam

2 from Albania, Japan, Kenya, Sweden

1 from Antigua, Australia, Austria, Bahamas, Brazil, Burma, Cameroon, Canada, Czech Republic, Congo (Brazzaville), Ecuador, Egypt, Estonia, Gabon, Georgia, Ghana, Greece, Italy, Jamaica, Kazakhstan, Lithuania, Malaysia, Netherlands, Panama, Russia, Uganda, United Kingdom, Zimbabwe. (Office of the President)

Participants

Recruiting Volunteers

I planned to use two methods to recruit participants. I intended to use purposeful sampling since richer data can be gleaned from students from different backgrounds rather than from the same background. This kind of sample could provide a variety of attitudes, insights, and understanding the researcher is pursuing (Merriam). For purposeful sampling, I sought the assistance of the Assistant Director of International Programs, who interacted with students at a function for international students, discussed my research with the students, and invited them to participate in the study on my behalf. Those students who were interested told the Assistant Director, who then forwarded their names and email addresses to me. Then, I contacted the students via email. Three students responded and decided to participate based on our email conversations; I met with them in the writing center, where they signed the consent form. None of them, however, made consistent appointments in the writing center, so I was unable to use them in the study.

I also employed convenience sampling (Creswell) which was more successful. When students entered the writing center for their scheduled appointments, I spoke to them about my study. I asked them if they regularly used the writing center and, if so, if they would be willing to participate in my study. Four agreed. Refer to Table 1 for details regarding the ML tutees.

To recruit the tutors, I gathered a list of interested volunteers during a writing center staff meeting. All participants, 18 years of age and older, met with me in the writing center to sign the consent form. Refer to Table 2.

Data Collection

I audio-recorded all sessions, observed, and took notes, reflecting my interpretations, insights, and themes, which allowed me to examine the students’ non-verbal behaviors (Creswell). Additionally, I held separate focus group interviews with the ML students and the tutors.

Audio Recordings and Coding

Throughout the semester, the four ML participants made numerous appointments with various tutor participants. Appointments run for two standard amounts of time, 50 and 25 minutes. I recorded 23 sessions from week three to week fourteen 14 of the fall semester. Based on the quality of the audio recordings, I chose 20 interactions to transcribe. Out of 20, 10 appointments were scheduled for 50-minute slots, and coincidentally, 10 were scheduled for 25-minute slots. This totaled nearly 15 hours of interactions. I transcribed all the tutoring sessions, utilizing the computer software program Temi, and then manually edited all transcriptions verbatim to capture utterances, pauses, and repetitions (Bucholtz). Once I completed the transcriptions, I uploaded all twenty into Dedoose, an online software program designed for analyzing qualitative data. After I reviewed the transcriptions multiple times, I employed Open Coding, a flexible, unrestricted approach, to code for common, recurring themes (Saldaña). I noticed several themes that emerged: corrections, directiveness, voice, dominance, negotiation, questions, and self-doubt (see Table 3).

From the 200-plus initially coded passages, my second cycle of coding relied on choosing codes based on Saldaña’s book, An Introduction to Codes and Coding: The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. The two most common, overarching themes emerged: “correction” and “negotiation” based on frequency (Saldaña):

Tutor provided correction by seeking perfection, appropriating tutee’s language, and taking autonomy (See Table 4).

Tutor and tutee negotiated through conversation, collaboration, clarification requests, comprehension checks, and confirmation checks (See Table 5).

Table 6 illustrates that I coded “correction” and “negotiation” 265 times: 177 for “correction” and 88 for “negotiation.” These were the two most frequently coded themes (Saldaña).

Table 7 shows the number of times I applied the specific codes of “correction” and “negotiation” to each of the ML tutees’ interactions. Of importance, in Amani’s and Alyia’s sessions, their tutors corrected more often than they negotiated: 73% and 79%, respectively. Consequently, I chose excerpts from these sessions to apply Critical Discourse Analysis in the next section.

Observations and Field Notes

During the writing center session, I also observed and took notes that reflected my interpretations, insights, and themes (Creswell). These observations gave me the opportunity to examine the students’ non-verbal behaviors, especially for those who did not feel comfortable speaking or who had difficulty speaking during their session (Creswell). Schwandt claimed that a researcher can support how their evidence is reliable by “examining its source and the procedures by which it was produced” (as cited in Roulston 201). Observations showed if the tutors took control of the tutees’ computers or hard copies of their writing and if the tutor allowed the tutee to maintain control of their work. What transpired in the writing center sessions helped to inform the content and questions of the focus group interviews.

Focus Group Interviews

I planned to hold focus group interviews in week 14, with all four of the ML students and with the six peer tutors, separately, but in the writing center. For many reasons that I was unable to predict in the planning stages of this research design, i.e., life-school balance, forgetfulness, potential disinterest, and some I was unable to identify, the ML students did not meet altogether. Two pairs met with me at two different times; instead of a focus group interview with four ML students, I held mini focus group interviews with two ML students twice. I still achieved the goal of interviewing ML students with another ML student present; in this context, students might feel more comfortable speaking up with other participants than in individual interviews as group interaction could facilitate the revelation of experiences, opinions, and attitudes. These interactions were helpful in getting participants to express their feelings. The participants also had the opportunity to share and compare experiences and different perspectives were ignited. Besides, the power dynamic shifted since ML students were together speaking (Krueger). In addition to the benefits of focus group interviews, Creswell suggested that researchers conduct them to augment data collection and triangulate multiple points of data. I also shaped the questions based on the students’ comfort level and reactions and on what I observed in the writing center sessions.

Critical Discourse Analysis

This study highlights the critical analysis of two excerpts that I coded for the recurring themes of “negotiation” and “correction.” In the original study, I chose three as a representative group, which is in line with the CDA literature (Fernsten; Kang and Dykema; Pigliacelli). Using Critical Discourse Analysis as a methodology examines the discourse between the tutors and tutees and allows a researcher to uncover relationships between participants and to interpret texts and move beyond the surface level (Fairclough; Mumby and Clair; Sarangi and Roberts) while investigating the relationships between discourse and other social factors like power, inequality, values, and beliefs (van Dijk; Fairclough and Wodak). Applying CDA to selected transcripts, I investigated if and how the interactions of tutors and ML tutees exhibited inequalities in power and authority.

I applied Fairclough’s three aspects of analysis: textual, interactional, and interdiscursive. The first level describes textual and linguistic features, e.g., voice, pronouns, and modality (Fairclough). The first level answers the following questions: What is happening? What are the activities, topic, and purpose? What are the textual features of the written or spoken words? (Fairclough). For instance, declaratives, first-person pronouns, lack of interrogatives, and vocabulary indicate authority (Severino; Thonus; Williams).

The second level, interactional, involves interpretations of the text and an “examination of discursive practice” which is how the text is produced, distributed, and received by the listener (Fairclough 78). The second level of analysis addresses who is involved, including the subjects’ positions and identities. Individuals’ turn-taking, topic choice, and control of the agenda affect the power and dominance of the interactions (Chang; Locke; Severino; Thonus). According to Locke, speech acts, i.e., “promises, declarations, requests, threats … evince particular social and power relations” (47). Thonus added three additional characteristics of dominance: less mitigation (more imperatives), shorter negotiations, and “holding the floor” (“Dominance” 228). Williams included “directives, interruptions, and unmitigated suggestions” (45) while Bell and Elledge mentioned “time-at-talk” (23) and control of session content. Severino maintained that tutors dominate their sessions with ML tutees as tutees use more backchanneling and fewer responses.

The third and final level, interdiscursive, involves an analysis of text in social contexts. Vital to this level is the idea of “ideology,” which is both in the structure of discourse and in the production of the discourse (Fairclough). Language is situated in context with “wider political, social, historical, and cultural discourses. These wider discourses may come from the immediate conditions of the situational context and the more remote conditions of institutions and social structures” (Fairclough 26). Interdiscursivity, or sociocultural practice, addresses the role of language and the connection to the social context (e.g., power, hierarchy, authority) (Fairclough; Locke) and the analysis is aimed at exploring if the discourse supports a specific type of dominant conversation or ideology (Locke). Tutors may feel pressure from the institution and their tutees as they attempt to satisfy the expectations of the institution (by giving knowledge) and their clients (Locke; Trimbur). Bailey adds that the “expectation that writing centers should ‘fix’ the English of international ESL students ties in with broader assumptions that privilege monolingual Euro-American viewpoints” (1).

To investigate if and how inequalities in power and authority were evident in interactions between tutors and ML tutees, I applied CDA to three excerpts in the original study, but here I present two: one from Gabriela and one from Amani. I used the following transcription conventions, modified from Williams:

Case 1: Gabriela

Gabriela was a senior undergraduate student from Venezuela who graduated in May 2020. During our focus group interviews, she told us that she had been in the U.S. for ten years, four of which were spent in high school. Her high school experience was not very “friendly,” and she struggled with the language barrier. The teachers were not understanding of “ESL” students, and she did not receive the support she wanted or needed. Once she graduated, she attended a community college for two years. In an encounter that changed the course of her learning, she earned a zero on a paper because she did not cite direct quotations. To revise, Gabriela sought the support of the writing center because “writing papers became [her] biggest fear.” She said that she felt she improved in so many areas, including sentence structure, making outlines, and using sources, and mentioned that she learned more from her visits to the writing center than in her writing classes.

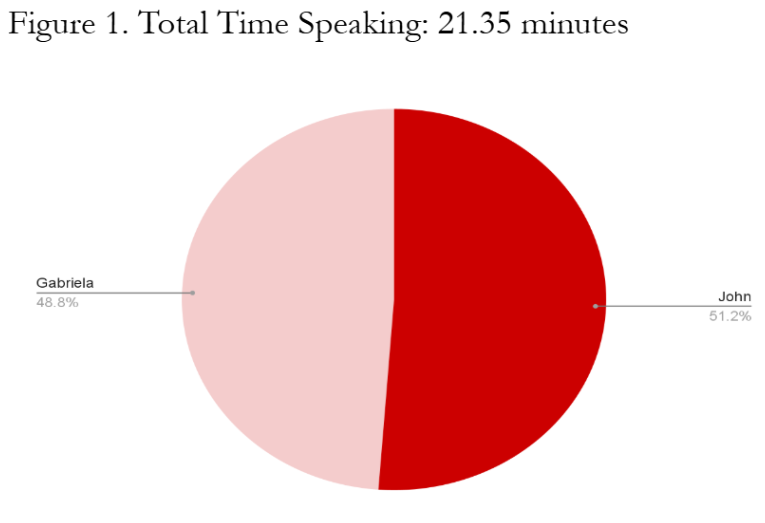

The following figure shows that Gabriella and John each spoke for about half the time. The times do not include reading silently or writing down information (Bell and Elledge).

I recorded five of Gabriela’s sessions, totaling over 266 minutes (about 4 and a half hours). In this session, Gabriela asked for assistance with her grammatical accuracy in her draft of a research paper for a business class. Analyzing the discourse critically revealed that Gabriela and her tutor, John, used questions and conversation to negotiate meaning, maintaining equal roles. The textual analysis showed that Gabriela and John used negotiations to clarify meaning; the tutor employed hedges and suggestions, allowing Gabriela to maintain power over her own writing. The interactional analysis illustrated that by balancing turn-taking, Gabriela and the tutor both possessed authority, although Gabriela interrupted and challenged the tutor, which emphasized her dominance. The interdiscursive analysis revealed that no power struggles existed and that both Gabriela and the tutor contributed equally to maintain collaboration.

Textual Analysis

The textual analysis showed that through tutor hedges and suggestions (van Dijk) and the tutor’s and Gabriela’s interrogatives in the form of clarification requests and comprehension checks, they collaborated and maintained equal roles. In Gabriela’s first turn in this excerpt, she read her paper aloud. The tutor then offered a suggestion, hedging it by saying, “There’s probably more in that one sentence than there needs to be” (my italics). Gabriela replied with laughter and affirmation, “Ok.” The tutor offered another recommendation, “What if we say…?” Here he used a suggestion followed by the first-person plural pronoun “we.” His choices indicated that his role is not one of authority but a collaborator, involving Gabriela in the choices for revision. Gabriela replied to his suggestions with backchannels, “Mmhm,” which affirmed the tutor’s suggestions since Gabriela kept the conversation moving forward. The tutor and Gabriela both utilized interrogatives in the form of clarification checks and comprehension checks. The tutor clarified: “Are the multiple reports… another thing that indicated that it was not the right thing to do?” In one instance when the tutor asked, “Multiple reports of employee injuries?” Gabriela clarified to make her meaning clearer: “It was more than injuries. It was deaths.” The textual analysis illustrated how Gabriela and the tutor distributed their power and authority equally by the following choices: 1) Gabriela’s use of interrogatives and her ability to maintain the conversation; 2) the tutor’s use of hedges, first-person plural pronouns, suggestions, and interrogatives. The textual analysis represented how the tutee’s and tutor’s choices facilitated collaboration and the co-construction of meaning.

Interactional Analysis

In the interactional analysis, the tutor’s choices signified the balance of power and authority. Their interactions illustrated collaboration and co-construction of meaning using clarification requests and comprehension checks. They both asked and answered questions, maintaining an equal balance in turn-taking (Williams). For instance, Gabriela asked, “How you say when you ignore something, like negligence, to listen negligence to?” The tutor, understanding Gabriela’s meaning, suggested, “ignoring... that they ignored reports…” (my italics). Gabriela and the tutor negotiated effectively by clarifying meaning. Gabriela’s initiation of the question “how you say... negligence…?” also indicated Gabriela’s agency and authority over her own voice. The tutor allowed this to occur by not exerting dominance and control. By choosing to use clarification requests and comprehension checks to negotiate meaning effectively, maintaining a balance in turn-taking, and exerting agency, Gabriela and the tutor illustrated an interaction that represented equality.

Interdiscursive Analysis

The tutor exerted no power or authority during his interaction with Gabriela, who created her identity as leader and author of her own session. The tutor made no choices to become the dominant speaker in the interaction. Both Gabriela and the tutor contributed equally. In one instance, Gabriela interrupted the tutor, exerting her power and authority:

Tutor: Okay. So--

G: And this one collapsed, like to collapse and then the other one was a fire.

The tutor worked at maintaining collaboration with Gabriela by providing her with time to ask questions and to respond to his questions. The tutor did not monopolize the session but promoted a “productive collaborative relationship” (Pigliacelli 12). No power struggles existed, and both Gabriela and John contributed equally to maintain collaboration. We can attribute this to Gabriela’s exertion of agency; she set the agenda, led the session, and interrupted the tutor to redirect the session. Gabriela knew the kind of assistance that she wanted and knew how to ask for it.

Case 2: Amani

Amani was a first-year graduate student in a master’s program and had been studying in the U.S. for two years. She started visiting the writing center for help with errors in grammar and spelling because “other people couldn’t understand what [she] was writing.” She found, though, that her previous experiences in the writing center helped her “emotionally” when tutors “encouraged [her] to keep going.”

I recorded three of Amani’s sessions, totaling over 169 minutes. In the example below, Amani met with tutor Rob and asked for assistance in creating an outline for her research paper, “Impact of Technology on Patient Experience,” about healthcare management. The following pie chart indicates the speaking time for the tutor and the tutee. The times do not include reading silently or writing down information (Bell and Elledge). Rob spoke for 4/5 of the session; he was not available for a focus group interview.

The excerpt below shows how the tutor controlled the session, limiting Amani’s opportunities to communicate. In many examples, Rob monopolized the time talking about what he would do, write, or say, not encouraging Amani to participate. Analyzing the discourse critically illustrated the inequalities in power and authority.

Textual Analysis

The textual analysis shows that the tutor’s use of the first-person pronoun “I” (in italics) and vocabulary (in italics) that appeared to be beyond Amani’s level of comprehension prevented collaboration and conversation. The tutor’s lexical choices also revealed his authority over Amani, even though he might not have intended to be the only participant with power. By using “CRISPR” and “HIV,” the tutor moved the focus away from Amani since these vocabulary words were not connected to her topic, and they stifled conversation as Amani replied with a backchannel, “Mm.” The language the tutor used prevented collaboration and co-construction of meaning. The tutor’s lack of interrogatives (Williams) also indicated his authority. Instead of asking Amani questions about her thoughts on the topic, he persisted with declaratives regarding his own ideas. The tutor’s use of the first-person pronoun “I,” his vocabulary choices, and his lack of interrogatives revealed his influence and authority.

Interactional Analysis

In the interactional analysis, the tutor’s use of longer turns and interruption (Williams) demonstrated his dominance and power. We can witness the tutor’s dominance when he centered the interaction on himself: “That’s how I would write it.” Instead of involving Amani in her own learning, he focused on how he would write the outline on a topic that is not in his field. In the three-and-a-half-minute excerpt, Amani used nine words, speaking for only 3 seconds. While Rob tried to suggest that Amani focus on more than the financial aspect, his 208 seconds of speaking prevented Amani from using her voice to suggest the points she would want in her outline.

The tutor also interrupted Amani, another indication of his dominance (Williams); she was unable to ask a complete question. He cut her off, defending his power and dominance (Fairclough). Amani did eventually ask her entire question about choosing one idea, but the tutor chose the agenda, replying in a long-winded response about topics knowledgeable to him. He removed power from Amani by monopolizing the interaction, preventing Amani from expressing her voice. As a result, Amani maintained a submissive role, enabling the tutor to lead the session. The tutor’s longer turns and interruptions (Williams) revealed his role of authority.

Interdiscursive Analysis

The tutor, a member of a larger context, a university writing center, established authority and power. The tutor created his identity as the active speaker in the session, fulfilling his role as the expert in this institutional context. Trimbur mentions that “many tutors feel a loyalty to both the institution that has awarded them the label of ‘writing expert’ as well as to their own peers who share their concerns as students” (290-291). Tutors feel “pulled, on one hand, by their loyalty to their fellow students and, on the other hand, by loyalty to the academic system that has rewarded them and whose values they have internalized” (Trimbur 290). The tutor wielded authority by monopolizing the session and choosing the topics upon which to expand: “Here’s what I would do...like I said…” Amani maintained the submissive role since she only responded with two short questions, one of which the tutor interrupted (in italics), and the backchannel, “Mm.”

The results of the CDA illustrate the inequalities in power and authority through Rob’s and Amani’s discourse choices in the context of a university writing center. The following illustrated Rob’s control, dominance, and power (Bell and Elledge; Fairclough; Hyland; Luke; Pigliacelli; Ritter; Severino; Thonus; Williams; Wodak and Meyer; van Dijk):

Controlling the agenda or topic choice

Longer turns and time at talk

Interruptions

The first-person pronoun “I”

Imperatives

Lack of interrogatives

Lexical choices (vocabulary)

Unmitigated suggestions

The following indicated Amani’s inferiority or submission (Bell and Elledge; Fairclough; Hyland; Luke; Pigliacelli; Ritter; Severino; Thonus; Williams; Wodak and Meyer; van Dijk), allowing the tutor to monopolize the session:

Shorter turns

Little or no control of the agenda or topic

Backchannels

Fewer responses

Less mitigation

The results of applying the Critical Discourse Analysis expose the disparity in power and authority through one tutors’ discourse choices and demonstrate the tutors’ lack of understanding regarding the needs of ML writers. Amani’s and Rob’s case elucidates how the tutor dominated the session by spending more time speaking and correcting grammar errors while suggesting accurate language use over the negotiation of meaning. However, Gabriela’s and John’s case illustrates how tutor and tutee used questions and conversation to negotiate meaning, maintaining equal roles. No power struggles existed; both Gabriela and the tutor contributed equally to maintain collaboration.

Discussion and Conclusion

The transcriptions and critical discourse analyses revealed distinctive findings across two case studies. The session between Gabriela and John showed a balanced, equitable interaction, where they cooperated and scaffolded their interaction by negotiating meaning and asking clarifying questions. Gabriela maintained agency over her learning and guided the interaction effectively. She was an active learner in the session, and the tutor allowed space for collaboration and conversation to occur. Conversely, the session between Amani and Rob revealed a major imbalance, where the tutor used an authoritative style that stifled collaboration. The discourse choices that Rob made contributed to his position of power and privilege, evident in the way that he assumed authority over Amani, reinforcing social hierarchies. Diving deeper into the cases of Gabriela and Amani, tutors can learn how discourse choices illustrate dominance, authority, and privilege.

Textual Analysis

Analyzing the transcripts from Amani and Rob’s interaction showed how the tutor exhibited his power and privilege. In terms of Rob’s textual choices, his continuous use of the first-person pronoun “I” and his lexical choices inhibited conversation and collaboration. The interactional analysis revealed Rob’s dominance and authority by his extended speaking turns and interruptions.

In contrast, by unpacking Gabriela and John’s session, we learn from the transcriptions and analysis that Gabriela and John worked collaboratively. For instance, the textual analysis revealed that John engaged in negotiations to clarify meaning and he employed hedges (e.g., “There’s probably more in that sentence than there needs to be”) and suggestions using the first-person plural pronoun (e.g., “What if we say…?”) These textual choices allowed Gabriela to maintain power over her own writing. John consistently asked questions that expanded their conversation and encouraged collaboration: “Are the multiple reports… another thing that indicated that it was not the right thing to do?” In another instance when the tutor asked, “Multiple reports of employee injuries?” Gabriela was able to expand her meaning to make it clearer: “It was more than injuries. It was deaths.” Tutors can learn that their textual choices can facilitate – or hinder– conversation and collaboration.

Interactional Analysis

The interactional analysis showed that Rob spoke over 80% of the time, controlling the agenda and the entire session. His longer time-at-talk and interruptions exhibited his power and authority. Especially disturbing is his “unmitigated suggestion” (Williams 45): “That’s how I would write it,” signaling that his voice is more authoritative than Amani’s, eliminating her power and voice.

If we contrast this with the interactional analysis of Gabriela’s and John’s session, we can see shared authority through balanced turn-taking as Gabriela controlled the agenda. John’s discourse choices facilitated a session filled with equality and a lack of dominance as John allowed space for Gabriela’s voice.

Interdiscursive Analysis

From the interdiscursive analysis, we can learn how Rob’s discourse choices reinforced his power and authority. By dominating the session, he exerted his privilege of “writing expert” (Trimbur 290) and reinforced linguistic hegemony. He might have been conforming to an unrealistic expectation to “fix” ML writing (Bailey), but Rob was not available for the focus group interviews. Amani conformed to a passive role as tutee as Rob created no space for her to participate.

On the contrary, Gabriela’s and John’s interaction showed no power struggle as they were equally engaged in the conversation. The analysis showed that John did not exert control or authority during their interaction. John’s goal was to interact with Gabriela and not modify her voice for the expectations of professors as he mentioned in the focus group interview.

Based on these findings, how can writing centers adopt a responsible and equitable approach, considering our understanding of multilingual writing and the dominance of linguistic hegemony? Implementing CDA is one path forward, and, in your busy writing center, training does not have to be arduous. Once a tutor gets permission from their tutee to record their session, a tutor can record and transcribe the interaction. The tutor can analyze the interaction by applying the three levels (Fairclough): textual (e.g., pronouns, modality, interrogatives); interactional (e.g., turn-taking, topic choice, and control of the agenda); and interdiscursive (e.g., situational or social context and potential expectations of the context or institution). Applying CDA, as opposed to observing or viewing a recorded session, allows tutors to dissect their discourse choices, examining how they negotiate conversations to facilitate collaboration or how they might inadvertently dominate a session. This analysis and introspection can lead to more productive discourse choices that encourage cooperation, enabling tutors to recognize and appreciate the ML writer’s voice.

Limitations

Limitations to this study included 1) unpredictability of students; 2) researcher bias; and 3) time frame. The original plan for this study described three tutor-tutee pairs who would meet three times during the semester. However, due to the unpredictability and conflicting schedules of the ML tutees, most of the ML participants were not able to meet with the same tutor several times. In the end, I observed and recorded the four ML tutees who met 23 times with five NS tutors over 11 weeks. This allowed for more data collection which increased my ability to make more interpretations and connections among data. Another limitation was the fact that I was the only researcher who collected and analyzed the data. My positionality and/or bias could have affected my interpretations of the data. The rigorous methods and recursive processes of analyzing data, however, guided my interpretations and explanations and accurately represented the concentrated results for which this study was aiming. The last potential limitation was the timeframe. I gathered data over 11 weeks because of the structure of the university semester.

This study presents two case studies valuable for tutor training, highlighting opportunities for critical discussions about tutoring sessions and the implications of tutor choices. If tutors aspire to maintain collaborative interactions with ML writers that lead to learning and growth, then tutors must hold space for their tutees to participate in the interactions. From this study’s transcriptions and analyses, tutors can understand that their discourse choices often reinforce linguistic dominance, thereby silencing students and erasing their identities as multilingual writers. As a result, tutors must be more conscious of their choices to avoid creating a power imbalance during writing center sessions. Tutors who work with ML writers can switch their focus from correction to encouraging interaction and collaboration so learning occurs while still maintaining the tutee’s voice and identity in their writing.

Works Cited

Akhmad, Fatmawati. “Dominance in Writing Center Tutorials for ESL Students.” Parahikma Journal of Education and Integrated Sciences, vol. 1, no. 2, 2021, pp. 16-24.

Anonymous Staff. Personal Interview. 16 October 2019.

Bailey, Steven. “Tutor Handbooks: Heuristic Texts for Negotiating Difference in a Globalized World.” Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, vol. 9, no. 6, 2012.

Bell, Diana Calhoun, and Sara Redington Elledge. "Dominance and Peer Tutoring Sessions with English Language Learners." Learning Assistance Review 13.1, 2008, pp. 17-30.

Brooks, Jeff. "Minimalist Tutoring: Making the Student Do All the Work." Writing Lab Newsletter vol. 15 no. 6, February 1991, pp. 1-4.

Bucholtz, Mary. “The Politics of Transcription.” Journal of Pragmatics, vol. 32, no. 10, Elsevier BV, Sept. 2000, pp. 1439–1465.

Canagarajah, A. Suresh. "The Place of World Englishes in Composition: Pluralization Continued." College Composition & Communication, vol. 57, no. 4, 2006, 586-619.

Canagarajah, Suresh. "Multilingual Writers and the Academic Community: Towards a Critical Relationship." Journal of English for Academic Purposes vol. 1, no. 1, 2002, pp. 29-44.

Chang, YiBoon. "Politeness Strategy Use and Dynamics of Dominance in College ESL Writing Tutorials: Building Social Relationships in the Non-Writing Discourse Frame.” Vol. 48, no. 1, 2012, 115-147.

College Factual. “Anonymous University.” 2017/18.

Collier, Virginia P. "How long? A synthesis of research on academic achievement in a second language." The New Immigrant and Language. Routledge, 2014, pp. 49-71.

Creswell, John. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches, Thousand Oaks, Sage, 2013.

Dees, Sarah, Beth Godbee, and Moira Ozias. "Navigating Conversational Turns: Grounding Difficult Discussions on Racism." Praxis, A Writing Center Journal, vol. 5, no. 1, 2007, pp. 1-7.

Dina. Personal Interview. 17 October 2019.

Ellis, Rod. “Task-based Research and Language Pedagogy.” Language Teaching Research, vol. 4, no. 3, 2000, pp. 193-220.

Fairclough, Norman. Language and Power, London: Longman. 1989.

Fairclough, Norman, and Ruth Wodak. “Critical Discourse Analysis.” In vanDijk’s Discourse Studies: A Multidisciplinary Introduction, vol 2, 1997, pp. 258-284.

Fernsten, Linda A. “Writer Identity and ESL Learners.” Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy: A Journal from the International Reading Association, vol. 52, no. 1, Wiley, Sept. 2008, pp. 44–52.

Gabriela. Personal Interview. 18 October 2019.

Hyland, Ken. "Authority and Invisibility: Authorial Identity in Academic Writing." Journal of Pragmatics vol. 34, no. 8, 2002, pp. 1091-1112.

Inoue, Asao B. "Afterword: Narratives that determine writers and social justice writing center work." Praxis: A Writing Center Journal. Vol 14, No 1 (2016).

John. Personal Interview. 18 October 2019.

Kang, Hee-Seung, and Julie Dykema. "Critical Discourse Analysis of Student Responses to Teacher Feedback on Student Writing." Journal of Response to Writing, vol. 3, no. 2, 2017.

Krueger, Richard A. Analyzing and Reporting Focus Group Results. Sage, 1998.

Leki, Ilona.Understanding ESL Writers: A Guide for Teachers. Heinemann, 1992.

Locke, Terry. Critical Discourse Analysis: Critical Discourse Analysis As Research, Bloomsbury Publishing, 2004. ProQuest Ebook Central.

Luke, Allan. “Chapter 1: Text and Discourse in Education: An Introduction to Critical Discourse Analysis.” Review of Research in Education, vol. 21, no. 1 Jan. 1995, pp. 3–48.

Lunsford, Andrea. “Collaboration, Control, and the Idea of a Writing Center.” The Writing Center Journal, vol. 12, no. 1, 1991, pp. 3-10.

Matsuda, Paul. "Teaching Composition in the Multilingual World: Second Language Writing in Composition Studies." Exploring Composition Studies: Sites, Issues, and Perspectives. Utah State University Press, 2012. 36-51.

Matsuda, Paul Kei, and Michelle Cox. "Reading an ESL Writer's Text." Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, vol. 2, no. 1, 2011, pp. 4–14.

Merriam, S. B. Qualitative Research and Case Study Applications in Education. Jossey-Bass, 1998.

Mitchell, Douglas E., Tom Destino, and Rita Karam. "Evaluation of English Language Development Programs in the Santa Ana Unified School District. A Report on Data System Reliability and Statistical Modeling of Program Impacts." 1997.

Morgan, D. L. Focus groups as qualitative research (2nd ed.). Sage, 1997.

Mumby, Dennis, and Robin Clair. "Organizational Discourse." Discourse Studies, 1997.

Office of the President. Anonymous University. 2017.

Pica, Teresa. “Research on Negotiation: What Does It Reveal about Second Language Acquisition?” Language Learning, vol. 44, 1994, pp. 493–527.

Pigliacelli, Mary. Practitioner Action Research on Writing Center Tutor Training: Critical Discourse Analysis of Reflections on Video-Recorded Sessions (Doctoral dissertation, Long Island University, CW Post Center). 2017.

Ritter, Jennifer Joy. Negotiating the Center: An Analysis of writing tutorial interactions between ESL learners and native-English speaking writing center tutors. (Doctoral Dissertation, Indiana University of Pennsylvania,). 2002.

Roulston, Kathryn. "Considering quality in qualitative interviewing." Qualitative research vol. 10, no. 2, 2010, pp. 199-228.

Saldaña, Johnny. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. 3rd edition. Sage, 2016.

Sarangi, Srikant, and Celia Roberts. "The Dynamics of Interactional and Institutional Orders in Work-Related Settings." Talk, Work and Institutional Order: Discourse in Medical, Mediation and Management Settings, 160, 1999.

Severino, Carol. “Avoiding Appropriation.” Edited by S. Bruce and B. Rafoth, Tutoring Second Language Writers, 2009.

Severino, Carol, and Elizabeth Deifell. "Empowering L2 Tutoring: A Case Study of a Second Language Writers Vocabulary Learning." The Writing Center Journal, vol. 31, no. 1, 2011, pp. 25-54.

Shamoon, Linda K., and Deborah H. Burns. “A Critique of Pure Tutoring.” The Allyn and Bacon Guide to Writing Center Theory. Ed. Robert W. Barnett and Jacob S. Blumner. Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 2001, pp. 225-241

Thonus, Terese. “Dominance in Academic Writing Tutorials: Gender, Language Proficiency, and the Offering of Suggestions.” Discourse and Society, vol. 10, no. 2, Thousand Oaks, CA, 1999, pp. 225-248.

Trimbur, John. “Peer Tutoring: A Contradiction in Terms?” The Longman Guide to Writing Center Theory and Practice. Eds. Robert W. Barnett and Jacob S. Blumner. New York: Pearson Education, Inc. 2008, pp. 288-295.

van Dijk, Teun A. “Principles of Critical Discourse Analysis.” Discourse & Society, vol. 4, no. 2, SAGE Publications, Apr. 1993, pp. 249–283. https://doi.org10.1177/0957926593004002006.

Williams, Jessica. “Writing Center Interaction: Institutional Discourse and the Role of Peer Tutors.” Interlanguage Pragmatics, edited by Kathleen Bardovi-Harlig and Beverly Hartford, Routledge, 2005, pp. 37-66.

Wodak, Ruth., and Michael Meyer. “Critical Discourse Analysis: History, Agenda, Theory and Methodology.” Methods of Critical Discourse Analysis, vol. 2, 2009, pp. 1–33.