Praxis: A Writing Center Journal • Vol. 15, No. 3 (2018)

RAD Collaboration in the Writing Center: An Impact Study of Course-Embedded Writing Center Support on Student Writing in a Criminological Theory Course

Stacy Kastner

Brown University

stacy_kastner@brown.edu

Shelley Keith

University of Memphis

srkeith@memphis.edu

Laura Jean Kerr

Mississippi State University

ljk19@ msstate.edu

Kristen L. Stives

Mississippi State University

kls738@msstate.edu

Whitney Knight-Rorie

DeSoto County Schools

wknightrorie@gmail.com

Kiley Forsythe

Mississippi State University

kforsythe@distance.msstate.edu

Kayleigh Few

Mississippi State University

k.few@ msstate.edu

Jen Childs

Mississippi State University

jlg229@ msstate.edu

Jessica Moseley Lockhart

Mississippi State University

jsm534@msstate.edu

Abstract

Given numerous calls within the writing center community for replicable, aggregable, and data-driven (RAD) research, this article presents findings from a study of course-embedded writing center impact on student writing in a writing-intensive criminological theory course. The research team analyzed papers from two semesters of the same course: one where students were given extra credit for self-selecting to work with the writing center and one where course-embedded writing center support was implemented. A total of 162 papers were analyzed using two taxonomies in order to study writing center impact on (a) grammatical correctness (mechanics, relationships between words, clauses, and the whole paper), as well as (b) student engagement with and comprehension of course content. Findings show that students in the semester with course-embedded writing center support had fewer grammatical errors in three out of the four subcategories analyzed but that GPA was the strongest predictor of grammatical correctness. Findings also indicate that course-embedded writing center support was the strongest predictor of students’ engagement with and comprehension of course content for the one of the theories in each of their papers, but that the student’s GPA coming into the course was a stronger predictor of student’s engagement and comprehension of a second theory in each of their papers.

Whether ironic or avant-garde, early scholarship put forth an idea for writing centers (or writing labs) as rich and experimental research sites (Brannon and North; Gillam). Yet historical and contemporary calls for increased “data-based,” “emic,” “empirical,” and “rigorous” writing center scholarship have been well-documented (North; Harris; Boquet and Lerner; Babcock and Thonus; Pleasant et. al.). Driscoll and Perdue make a compelling quantitative case. In their analysis of replicable, aggregable, and data-driven (RAD) research published in Writing Center Journal (WCJ) between 1980 and 2006, they found that of 91 research articles, 63% relied on qualitative data, while only 13% relied on quantitative data. Slightly better, 17.4% use both qualitative and quantitative data (28). While Driscoll and Perdue did find that RAD research published in WCJ is increasing both in volume and quality, in the span of two and a half decades, only 13%—or 11.83 articles—were quantitative studies. Notably, this is not just a problem in the area of writing center research. Richard Haswell framed the situation apocalyptically in Nickoson and Sheridan’s 2012 critical methods text for writing studies researchers: “the need for quantitative research in the composition field is a crisis in itself” (186).

Crisis or not, the barriers to responding to these calls for RAD and quantitative writing center research are considerable and have likewise been well-documented. Quantitative methods are not standard coursework in Composition and Rhetoric programs or in the English Departments or other humanities-based disciplines that writing center directors may come from (Bromley, Northway, Schonberg; Driscoll and Perdue). The people who administer and tutor in writing centers do not necessarily identify as researchers and may not be required or have time to do any kind of research and writing as part of their administrative, faculty, or staff writing center assignments. In addition to the daunting layers of expertise demanded by quantitative writing research, this research is time-consuming, labor-intensive, and expensive. Despite these challenges, Doug Enders’ 2005 WLN “Qualitative Tale of a Quantitative Study” brings into focus why it is important for writing center directors to engineer their storytelling machines to produce direct measures:

Through reports on the number of students served, descriptions of the kinds of work center staff perform, and stories of student success and faculty satisfaction, writing center administrators have attested to the value of their centers. Increasingly, however, they are being asked to do this by measuring the writing center's impact on student grades or retention through quantitative analysis. (6)

As Enders’ piece demonstrates, the demands for a different kind of writing center assessment being articulated by institutional stakeholders within local contexts are plentiful and related to the scholarly literature in our own field that calls for a different kind of writing center research. If we look to discipline-specific journals that invite scholarship on teaching and learning, we will find that calls for more and different kinds of research on student writing are pervasive. An article about a writing-intensive criminal justice course that appeared in the Journal of Criminal Justice Education in 2006 observes that

Interestingly, very little formal research has been conducted not only in criminal justice but in other disciplines that examines either the reasons why students cannot write or offers practical solutions to remedy the problem. Instead, most of the information about the problem is shared anecdotally among educators. (122)

There are many ways to process this kind of WAC dialogue about student writing. The researchers of this article recommend an invitational interpretation: the teaching of writing is of interdisciplinary importance and our colleagues across the disciplines may have a research interest in learning more about what does and does not benefit students’ writing development in writing-intensive courses. None of us are, or at least do not have to be, researching by ourselves.

Generally well-trained and experienced text-based researchers, members of the writing center community are expert analysts, coders, interpreters, and narrators. The queries of social scientists often require the use of statistical analyses (quantitative methods) to make meaning from large amounts of data. This data could come from surveys or, just as easily, once it is codified, student writing. This article discusses results from one such fortuitous merging of writing center and social science expertise. Our writing center/criminological theory research team conducted a study of error, content engagement, and content comprehension in writing collected from students enrolled in an upper-level, required, writing-intensive theory course for criminology majors at a large southern research university. Four short papers without teacher commentary were collected from all students in two semesters of the same course, taught by the same professor both semesters. In fall 2014, students who chose to voluntarily work with the writing center received extra credit; in spring 2015, all students received course-embedded writing center support in the form of in-class mini lessons and were required to participate in one-on-one feedback and brainstorming meetings with a writing center staffer.

A total of 162 papers were analyzed using two taxonomies in order to study writing center impact on (a) grammatical correctness, as well as (b) student engagement with and comprehension of course content. To study writing center impact on correctness, influenced by the work of Lunsford and Lunsford, the research team coded twenty-four possible errors in student writing that were grouped into four broad error categories: mechanics, relationship between words, relationship between clauses, and whole paper. A lower error rate in the spring 2015 course compared to the error rate in the fall 2014 course in any of the four primary categories would demonstrate the effect of course-embedded writing support.

To study the writing center’s impact on students’ engagement with and comprehension of course content, the research team developed a content taxonomy for each paper. This taxonomy counted each time students listed, defined, and defined correctly concepts for each of the two theories they were responsible for covering in each of their papers. The research team equated correctly defined concepts with comprehension. Concepts that were listed and defined—regardless of accuracy—were equated with engagement. A higher proportion of concepts listed, defined, and/or defined correctly in the spring 2015 course compared to the fall 2014 course demonstrated positive course-embedded writing support impact.

Taking the lead from our colleagues in faculty development who use quantitative data to inform course design, particularly in the case of courses with high impacts (like a writing-intensive required disciplinary gateway course), after overviewing our findings, we briefly discussed the concrete outcome of our impact study: a revised course-embedded model of instruction responsive to what we learned from looking closely at student writing.

The Necessity of RAD Research in our Local Context

From the reflective student feedback received from fall 2014 when writing center visits were rewarded with extra credit, we went into our research knowing that the few students (five out of twenty-one) who did visit the writing center that semester felt, for the most part, that they had a positive experience. While one student had hoped the tutor they worked with had more personal knowledge about APA style, other students noted that they would return. Two students did return—one student using the writing center twice and another three times—and reported that they worked on both higher order (organizational, source use) and later order (formatting) concerns:

“My tutor helped me to organize my thoughts for my paper and helped me format my citations page.”

“She enlightened me by explaining that one can easily avoid similarity by reading something three times, turn your computer around, and then write down what you got from it in your own words.”

“They were all very friendly and helpful. I will definitely go back for help again.”

“They were not very knowledgeable of APA style. . . . They pull out manuals and point me to materials to help me.”

These student reflections tell specific and valuable stories about the writing center. Students who self-selected to work with the writing center reported learning concrete methods to help them with the paper they were working on at the time of their appointment. Their descriptions of their experiences suggest they learned flexible methods that they can use to help them with future papers as well—transferable skills, like how to incorporate secondary sources into their papers, how to structure arguments, and how to identify and use resources to answer questions about disciplinary style.

Though data-based, useful, and valuable, student reflections are not a direct measure. However, when the professor of the criminology course in this study was invited to speak at an event where faculty could learn more about the writing center, student reflections were the only data they could present to validate their rationale for incentivizing writing center visits for students in their writing-intensive course. They experienced a credibility crisis that is perhaps familiar to readers of this journal. Babcock and Thonus describe this situation in Researching the Writing Center: Towards an Evidence-Based Practice:

[C]omposition/rhetoric and writing center researchers need to do “serious researching” before we can sit at the head table and be taken seriously by our academic colleagues. In our view, writing center scholarship has been largely artistic or humanistic, rather than scientific, in a field where both perspectives can and must inform our practices. While theoretical investigations build the foundation for writing center studies, and anecdotal experience points in the direction of best practices, empirical research will create a credible link between the two. (3)

As Babcock and Thonus, Enders, and especially Neal Lerner’s “Counting Beans” pieces attest, our narrative of ourselves needs to be qualitative and quantitative. While it may not be realistic or even possible for some writing center directors to learn to do quantitative research, partnering with their WAC colleagues offers the possibility for quantitative assessments of the writing center in addition to best practice models for course-specific co-curricular writing support.

If our colleagues are teaching writing-intensive courses and trying to help students dance that WAC/WID tango of learning upper-level course content and also simultaneously learning how to write in disciplinary genres and styles for the first time, they know well the important role that writing will play beyond their classroom, and they have committed to helping students practice writing in their classroom because of it. They know how hard it is to teach and to learn writing and yet they are doing it anyway. These seem to be very good colleagues to build a writing research team with.

The Study

The National Council of Teachers of English’s (NCTE’s) 2016 Professional Knowledge for the Teaching of Writing suggested that students struggling with complicated content may not also be able to focus on grammatical correctness:

On the one hand, it is important for writing to be as correct as possible and for students to be able to produce correct texts so that readers can read and make meaning from them. On the other hand, achieving correctness is only one set of things writers must be able to do; a correct document empty of ideas or unsuited to its audience or purpose is not a good piece of writing. There is no formula for resolving this tension. Though it may be desirable both fluently to produce writing and to adhere to conventions, growth in fluency and control of conventions may not occur at the same time. If a student’s mental energies are focused on new intellectual challenges, he or she may attend less fully to details of grammar and punctuation.

For the purposes of our study, our goal was to investigate this hypothesis by identifying patterns of error in student writing from CRM 3603: Criminological Theory. Given the NCTE’s suspicions, we looked at error patterns in grammar and mechanics as well as students’ handling of the theoretical course material. We were interested to see if course-embedded writing support—not using a traditional, multi-draft, undergraduate writing fellows model—resulted in decreased grammar error rates and increased engagement with and comprehension of course content in students’ writing.

CRM 3603 focused on sociological explanations for the causes of crime. As explained to students in the course syllabus, the course was built upon foundational WID and writing-to-learn principles:

Through writing, you will learn to synthesize and refine your understanding of ideas and information. . . . [T]his course seeks to give you the opportunity to develop your writing and analytical skills within normal class work. (Keith)

Over the course of the semester, students wrote four out of a total possible six short papers, wrote a multiple-draft longer final seminar paper, and completed in-class quizzes as well as midterm and final exams. The expectations for student writing in the course were field-specific:

Scholars and practitioners in the criminal justice field value independent thought; the ability to gather, synthesize, and analyze evidence from diverse sources; and the ability to interpret theory and to apply theory to practice and practice to theory. (Cullick and Zawacki 37)

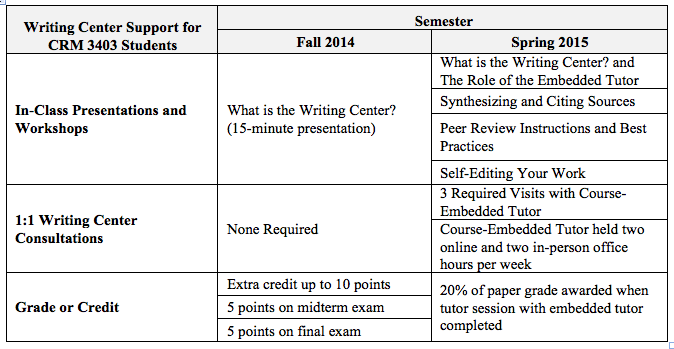

In fall 2014, the writing center offered a fifteen-minute presentation in class. Extra credit was offered to students who chose to use the writing center as they worked on their short papers. In spring 2015, course-embedded writing support was implemented. The co-assistant director of the writing center and lecturer in the composition program served as course-embedded tutors. They attended class meetings and kept in regular contact with the course professor and teaching assistant. They also held four open office hours per week for students in the course (two in person and two online). All students were required to attend three one-on-one meetings with the course-embedded tutor. As opposed to extra credit, in the spring, 20% of three of four short papers grades was awarded for students having made and attended their thirty-minute conference. In conferences, students were encouraged to review and reflect on the feedback they had received on a completed draft from the professor and/or teaching assistant (TA) in order to address or respond to that feedback in the context of an approaching deadline for their next short paper. These touch-point meetings were planned into the course to take place between their first and second papers, second and third papers, and third and fourth papers. Fig. 1 displays a side-by-side comparison of writing support in fall 2014 and spring 2015 (See Appendix A).

Based on discussions of students’ needs after the course professor and TA evaluated students’ papers, the course-embedded tutor also prepared and delivered four writing-focused mini lessons throughout the semester: (1) introduction to the role of the embedded tutor in the course, (2) synthesizing and citing sources, (3) peer review, and (4) self-editing. In their in-class presentation introducing course-embedded writing support, the course-embedded tutor explained to students,

Overall, I’m here to help you better understand what good writing means in your field, make effective use of your teachers’ comments and feedback on your writing, and, more generally, help you to build skills and strategies to respond, in writing, to particular audiences for particular purposes. (Forsythe)

For the purposes of this article, we analyzed the four short papers that students wrote. Though each student had only a single draft of each paper and they were distinct assignments, each employed an identical structure defining, explaining, comparing, and contrasting two major theories. The two theories were determined by the professor of the course for each paper and grouped together because they were related to each other. For example, the first theory (Theory A) was typically the foundational theory in the field and the second theory (Theory B) was an expansion or improvement upon the foundational theory.

We received IRB approval to seek student consent in class to collect the writing that students submitted for course evaluation and to obtain demographic data from the registrar’s office, including race, gender, and GPA. For each semester, a teaching assistant archived copies of student papers without teacher commentary. All identifying information was removed and each student was assigned a unique numeral ID. Demographic data obtained from the registrar’s office was added to our data set after coding results were recorded.

Our decision to implement a course-embedded writing support model was both pragmatic and ethical. Although we needed more students to make use of the writing center in order to have a sample size large enough for an impact study, given the misgivings surrounding required writing center appointments (Rendleman), we were cautious about how we balanced time spent on designing a rigorous quantitative writing assessment and designing a meaningful pedagogical intervention. In the end, course-embedded instruction seemed the best model. The success of such programs date back to the longstanding writing fellows program Tori Haring-Smith architectured at Brown University in the 1980s. Praxis’s 2014 double issue on more current course-embedded models of writing support— special guest edited by Russell Carpenter, Scott Whiddon, and Kevin Dvorak—is likewise testament to the continuing vibrancy and success of such programs.

Like Dara Rossman Regaignon and Pamela Bromley, we were interested in learning what the impact of course-embedded writing support was on the writing that students produced. Regaigon and Bromely studied a literature “gateway course” (though not a theory course), by collecting three papers from students enrolled in two sections of the same course. A different professor taught each section, and one section had course-embedded undergraduate writing fellows who provided written and verbal feedback on first drafts. The other section did not have writing fellows or multiple drafts. As stated by the authors:

Our hypothesis, based on the indirect data reported in the literature and on an earlier pilot study by Regaignon, was that all students’ writing would improve over the course of the semester, but that the writing of the students in the course with writing fellows would improve more than that of the students in the non-writing fellows course. (44)

In our own study, we hypothesized that, in the semester with course-embedded writing support, grammar error rates would be lower and the proportion of concepts listed, defined and correctly defined for each of the two theories student address in each of the four short papers that they completed would be higher.

Regaignon and Bromley’s impact study showed that

requiring students to submit drafts, receive written feedback from, and then talk through their work and their plans for revision with trained peer writing fellows results in a statistically significant improvement in their overall writing score over the course of the semester even when the final assignment is more difficult than those that preceded it. (50-51)

We were curious if our results would be similar, given that the students in our study were working on learning to apply feedback across different drafts (as opposed to applying feedback from a first draft to a final draft of the same paper), and given that our local context did not support a peer-to-peer traditional writing fellows model.

More importantly, in addition to the differences in the course contexts and course-embedded writing support models, the way we analyzed student writing and measured improvement also differed significantly from Regaignon and Bromley’s work. They asked their coders to approach student papers together (in the form of a portfolio) and to qualitatively rate each student paper, and then the portfolio as a whole, using an evaluative rubric. Coders assigned a 0-5 rating on five categories—Argument (statement of problem & thesis); Organization (structure and coherence); Evidence & Analysis; Use of Secondary Sources; Style (grammar/clarity as well as stylistic flair)—and then assigned a grade to the whole paper (60). In contrast, our goal was to use a rubric, a tool for analyzing and codifying student writing, that would allow us to closely describe what was happening in student writing in terms of both content mastery and grammatical correctness. In the end, we settled on two taxonomies. We built an error taxonomy mirroring Lunsford and Lunsford’s model in “‘Mistakes Are a Fact of Life’: A National Comparative Study.” and a content rubric we created that limited the necessity of qualitative judgment as much as possible (Did students list all elements of the theory? Did they define the theory, even if it was incorrectly defined? Did students correctly define the concepts from the theory?). We also did not look at student writing holistically, relying instead on statistical analyses to confirm or not if student writing improved based on objective measures (errors) from the beginning to the end of the semester.

Participants

As illustrated in Fig. 2 (see Appendix A), a total of 162 student papers were analyzed from 46 students enrolled in CRM 3603 during fall 2014 (20 students contributed 69 papers) and spring 2015 (26 students contributed 94 papers).¹ For fall, the average GPA for students before the end of the semester was 2.93, the lowest being 2.08 and the highest being 3.85. For spring, the average GPA for students before the end of the semester was 2.99, the lowest being 2.07 and the highest being 3.96. The grade point average was accessed via student transcripts before the completion of the semester under study and is on a standard 4.0 scale.

For both semesters combined, the number of males and females who agreed to participate was even, although the proportions varied by semester. The majority of participants were white (75% in fall and 65.4% in spring). In the fall, 20% of participants were African American and 5% were Hispanic. In the spring, 30.8% of participants were African American and 3.8% were Hispanic (see Fig. 3 in Appendix A).

Methods

Our key dependent variables included (1) grammar error rates and (2) the proportion of completion for students listing, defining, and correctly defining and interpreting all of the concepts central to the two theories they wrote about in each of the four short papers. In our statistical models, we controlled for gender (males coded as 1) and race, including white, Hispanic, and black with black as the reference (comparison) category. GPA and the addition of course-embedded writing center support served as independent variables (spring, the-course embedded semester, coded as 1). Setting GPA as an independent variable and race and gender as controls allowed us to temper our findings and acknowledge that all students are simply not “starting from the same point” (Lerner 2) both in terms of social location as well as academic preparation.

As noted, grammar and mechanics error rates were determined by developing and applying one taxonomy, and content errors were determined by developing and applying an additional taxonomy. Four writing center staff members formed the grammar/mechanics errors coding team. The course professor, spring 2015 course-embedded writing center tutor, and two former teaching assistants for this course—one of whom was the TA for the academic year during which data was collected—formed the content errors coding team. All coding was done in pairs to ensure validity and reliability. Data was initially recorded in SPSS and later exported to STATA for analyses. Before splitting into coding teams of two, each coding group of four underwent a norming process. First, the group applied a preliminary taxonomy draft to a sample paper under the guidance of the associate director of the writing center or the sociology professor. As discrepancies in application emerged, additional details or rules were inserted into the taxonomies to help guide coders’ work. It took multiple weeks of meeting to test, revise, and re-norm for both taxonomies.

Once revisions on each taxonomy were finalized, each group (grammar and mechanics group and content group) got together and applied their respective taxonomy to sample papers. Once the full group established a working application of the taxonomy, the group split into coding teams to apply the finalized taxonomy to two papers. After independently applying the taxonomy to the same papers, the teams met again with the associate director of the writing center and/or the sociology professor, to compare results. Finally, the full team of four coded an additional paper together; again, coders would split into two teams to code two additional papers. This process was repeated until teams’ independent applications of the taxonomies to the same papers were consistent. Once consistency in taxonomy application emerged, coders split into their teams of two, recoding all papers that had been previously coded in the norming process as well as the remaining papers.

Grammar/Mechanics Error Taxonomy

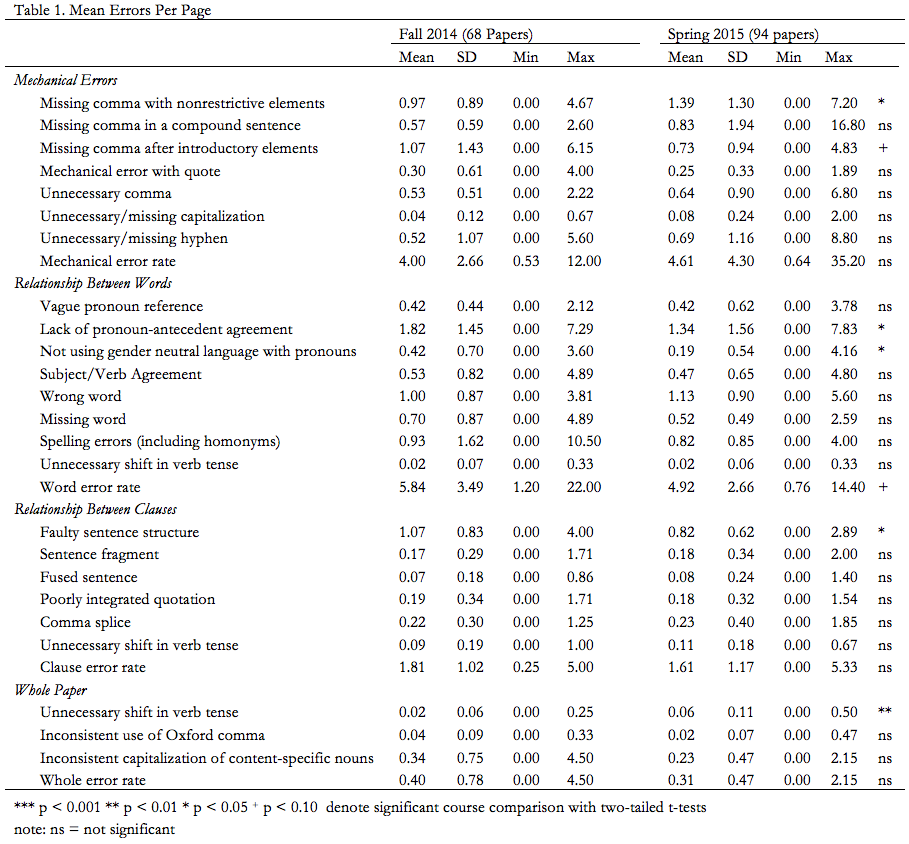

Starting with the twenty most common errors identified by Lunsford and Lunsford in 2006, the grammar/mechanics team settled on counting twenty-four different errors that were divided into four categories: (1) punctuation and capitalization, (2) relationship between words, (3) relationship between clauses, and (4) errors involving the whole paper (see Table 1 in Appendix A). Our coders used an indexed taxonomy to guide their coding. For each error, a definition was provided (with a link to additional information), and multiple examples of correct and incorrect applications were included to help coders with their work.

In order to compare the grammar/mechanics error rates between semesters to find out if a course-embedded writing center implementation resulted in fewer errors in student writing between four different papers than the fall 2014 course, an average error rate for each student was created by summing of all errors in each category divided by the total number of pages. Partial pages were estimated in quarters.

Content Taxonomy

Our content taxonomy was created by content coders (the sociology professor, embedded tutor, and two course TAs) for each paper assignment (four papers in total). Content was categorized and counted in three ways: (1) the number of concepts listed, (2) the number of concepts defined, and (3) the number of concepts defined correctly.

A concept was considered listed if the word or phrase was mentioned in the paper. It was considered defined if any explanation followed the listing of the concept, regardless of accuracy. Finally, a concept was considered defined correctly if an accurate definition or quotation was given followed by an example in the students’ own words.

For each paper, the number of concepts—listed, defined, or defined correctly—was divided by the total number of concepts for each theory to create a proportion for each student. This was completed for each theory expected in the paper with Theory A referring to the first theory the student was required to describe and Theory B referring to the second theory the student was required to describe.

Fig. 4 (see Appendix A) provides an example of one content taxonomy created for the second paper assigned to students, which required them to compare Classic Strain Theory (five concepts) with General Strain Theory (nineteen concepts).

Statistical Analyses

To determine if course-embedded writing center support increased grammatical correctness in student writing, we employed difference of means t-tests assuming unequal variances to compare mean error rates between the two semesters for our four broad error categories: mechanical errors, relationship between words errors, relationship between clauses errors, and whole paper errors as well as individual items within these categories (see Table 1 in Appendix A).

To examine if course-embedded writing support and GPA reduced the likelihood of grammar errors in student writing controlling for race and gender, we used STATA 12 to complete ordinary least squares (OLS) regressions with the cluster option, which adjusts the standard errors to take into account that each student had more than one paper in the dataset (see Table 2 in Appendix A).² We ran four regressions with the error rate for each broad category of error serving as dependent variables. Each model included the semester the student took the class, the overall GPA, and finally, the gender and the race of the student as control variables.

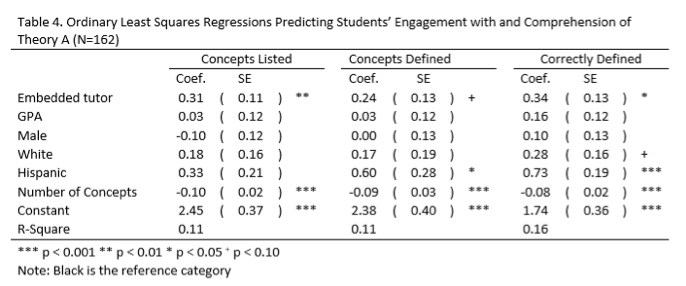

To investigate the impact of course-embedded writing center support on student engagement with (listed, defined) and comprehension of (correctly defined) course content in their papers, we compared the percentage of concepts listed, defined, and defined correctly for each theory within each of the six papers for the fall and spring semesters (see Table 3 in Appendix A). In order to assess whether the success percentages for each category differed by semester, we used equality of proportions tests.

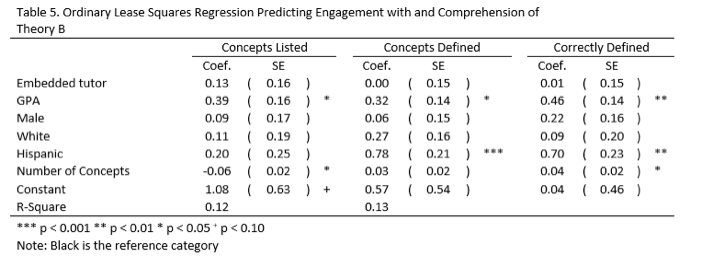

To assess the impact of course-embedded writing support and GPA coming into the course on listing, defining, and correctly defining Theory A and Theory B, Tables 4 and 5 include ordinary least squares regression analyses with the cluster option on student identification number (see Appendix A).³ In these models, we also controlled for the number of possible concepts for the theories described given that students may have an easier time covering theories with fewer concepts. Looking separately at Theories A and B allowed us to investigate not only if student writing improved but also if student writing improvement was reflected by the entire paper or particular portions of the paper, like the first half (Theory A) and second half (Theory B).

Findings

As illustrated in Table 1, we found that students in the semester with course-embedded tutoring tended to have longer papers, and, as illustrated in Table 1, they also had lower overall error rates than students in the comparison semester for three out of four of the possible broad error categories: relationship between words, relationship between clauses, and whole paper errors. Students in the spring, however, had a higher rate of mechanical errors. It is important to note that only the rate of relationship between words errors was marginally statistically significant (a rate of 4.92 errors per page in the spring as compared to 5.84 in the fall).

Table 2 provides an overview of results from the regression analyses predicting grammar errors. Course-embedded writing support was not a statistically significant predictor of correctness when GPA and race and gender were included in the models. Regardless of course-embedded writing support, students with higher GPAs coming to the course had lower mechanical error rates (p < .05) and lower relationship between clause error rates (p < .01). Course type and background characteristics did not affect word errors or whole paper errors.

Turning to our analysis of engagement with and comprehension of course content, it is important to note that students in both semesters were required to write four out of six short papers: two out of three possible papers in the first and second halves of the semester. Students in fall 2014 most often chose to write papers two, three, five, and six. Students in spring 2015 were required to write paper one and most self-selected to write paper three. Students in spring 2015 were also required to write paper four and most self-selected to write paper six. There is some indication that students in the semester with course-embedded writing support were better able to list, define, and define correctly the concepts (see Table 3). For example, for ten out of twelve papers, students enrolled in the spring semester defined a higher percentage of the theories in their papers correctly than those who were enrolled in the fall semester. In all cases excluding paper one (because students did not meet one-on-one with the course-embedded tutor) and with the exception of paper number three, students in the spring semester with course-embedded writing support were more likely to either list, define, and/or define theoretical concepts correctly for one or both of the two theories they were writing about (see Table 3). For paper six, a paper that the majority of students in both semesters self-selected to write, students were significantly more likely to define all concepts for Theory A and correctly define them in the spring semester with course-embedded writing support where students met with the course-embedded tutor to discuss instructor and teaching assistant feedback on their prior drafts before finishing and handing in paper six than in the class with no required involvement of the writing center. Additionally, students in the spring semester were required to meet with the course-embedded tutor between their first and second papers, second and third papers, and third and fourth papers.

Ordinary least squares regressions were used to determine if course-embedded writing support coming into the course and/or GPA were predictors of success for students listing, defining, and correctly defining concepts for Theories A and B. We found strong support for our hypothesis that course-embedded writing support would increase the likelihood of engagement with course content for Theory A. Specifically, course-embedded writing support significantly improved the likelihood of students listing concepts for the first theory they were required to write about while GPA, gender, and race were not significant predictors of success (see Table 4). Likewise, course-embedded writing support increased the likelihood that students defined concepts although the results were marginally significant (p < .10). Finally, students in the embedded support course were significantly more likely to demonstrate comprehension of course content (correctly define concepts) than those in the non-supported course. As expected, students were less likely to list, define, or correctly define concepts when the theories included more concepts.

Though course-embedded writing support had a positive impact on students’ engagement with (listing and defining) and comprehension of (correctly defining) course content in the first halves of their papers (Theory A), this was not the case for the second halves of their papers (Theory B). Table 5 illustrates that GPA coming into the course was a statistically significant predictor of success for students listing, defining, and correctly defining concepts in the second halves of their papers (Theory B).

Discussion

Our statistical analyses showed that students in the spring semester had fewer overall errors per page, and though they contained more surface-level grammar errors (mechanical errors like a missing comma), the papers demonstrated a higher level of engagement with and comprehension of course content. Controlling for GPA and other background characteristics, we found that the students in the spring semester had fewer grammatical errors in their papers, we found that it was GPA rather than course-embedded tutoring impacting this. In contrast, controlling for GPA in our content analysis, we found that course-embedded tutoring did positively impact students’ comprehension of Theory A in their papers. Interestingly, these results were not consistent for both the first and second theories. GPA, as opposed to course-embedded writing center support, was the main predictor of students’ successful engagement with and comprehension of Theory B. It may be that those with a higher GPA have better time management skills which allowed them enough time to fully address Theory A and Theory B in the paper. While course-embedded writing center support seemed to assist all students with the first halves of their papers (Theory A), it did not appear to nurture the kind of persistence students with lower GPAs coming into the course needed to employ in order to be successful through the entire paper (with both Theories A and B).

As we suspected, these findings add additional texture to the story of writing center impact that the student reflections included earlier in this article tell on their own. The findings of our textual analyses also tell a different story than simple direct measures that we might have used to investigate and confirm the positive impact of course-embedded writing support. For example, whereas only thirteen students from fall (65%) completed all four short papers, twenty-one students (80.8%) completed them all in spring. Students in the spring semester also wrote longer papers than students in the fall semester.

Though it may seem like this kind of objective writing center research has limitations in terms of qualifying our value, having localized and objective results to facilitate the redirection needed when WAC faculty seek writing center support for purposes of grammatical correctness is of no small value. Our study confirmed the NCTE’s hypothesis that students working through difficult content material “may attend less fully to details of grammar and punctuation.” The ability to marry pedagogic beliefs from a national organization with quantitative evidence validating those beliefs in the context of a study of students’ writing on one’s own campus is compelling, much more compelling than riffing writing studies theory and pedagogy with a colleague whose epistemic tradition has socialized them to seek objective and evidence-based praxis.

The goal of the one-on-one meetings with the course-embedded tutor was to help students process and implement feedback they received on their past drafts in the context of a new assignment. Knowing this, our findings demonstrate the difficulty that the writers we studied had transferring feedback from one writing assignment to another, even within the same course, even with the support of an embedded writing tutor, even when the structure of four assignments were almost identical (excepting variance in the number of concepts writers needed to list and define based on the specific theory they were writing about). Learning more about if and how writers can transfer feedback in the context of sequential assignments on distinct topics is an important avenue for further research. This is all the more true since the assumption that students should be able to apply feedback from one draft to a different draft is rampant (and maybe verifiably incorrect) in the WAC academy.

Designing a content taxonomy for our research helped to visualize the expectations of assignments. The taxonomy made visible both the complicated task of the student writer in these seemingly straightforward papers and the generous potential for making errors. As researchers, we needed two heavily indexed instruments and an almost overwhelming amount of practice and training in how to use them in order to be able to identify what made the student papers “incorrect.” What we learned from our study was, more than anything else, how difficult student writers’ tasks were in this course and how much they were struggling with writing, with reading and comprehending course material, and with writing about that course material. Of more pragmatic value, the criminology course was taught by the same professor consistently in both fall and spring semesters. Yet, each academic year, a new teaching assistant was assigned and needed to be mentored in assignment and paper expectations. Likewise, though the writing center consistently had the staff capacity to offer course-embedded support in spring, it did not have the same staff capacity in the fall when there were more sections of composition courses offered and thus significantly less staff in the writing center. In this sense, the content taxonomy also served as a guide for the ever-shifting roster of people serving as teaching assistants and writing center staff members on our campus.

Research-Responsive Pedagogy: Revised Course-Embedded Writing Center Support

Ultimately, our quantitative study helped us to design a research-responsive course-embedded writing center support model that supported students based on what they were struggling with. Looking closely at student writing, we made transparent how demanding the task of writing short papers was, in general, but also specifically in the context of students’ ability to synthesize theoretical material in writing (as Table 3 shows, for the majority of papers, the majority of students were listing 50% or less of the concepts for Theory B). Seeing this difficulty, we decreased their workloads, clarified as much as possible how the seemingly separate parts of a course built upon one another, and networked students as peers to sustain and support one another’s growth.

Our goals, then, in revising the course-embedded pilot were to: (1) decrease students’ workload, giving them more time to focus on being able to define, interpret, and apply the theories of crime covered in the course, (2) increase students’ awareness of how all of the course assignments related to one another, and (3) increase students’ confidence and competency with APA style. To achieve these goals, in spring 2016 when the writing center again had the capacity to offer course-embedded writing support, the course dropped the four short papers in favor of two notes assignments with accompanying small group peer review sessions that were graded based on labor (whether students completed the notes assignment, peer review, and participated in the small discussion group), rather than correctness (see Appendix B).

Students self-placed themselves into groups of four. They met twice, once before the midterm exam and once before the final exam. Each student was responsible for an informal “notes” piece. For the notes assignment, students were asked to (1) list all major components of each theory assigned to them, (2) write a one-page comparison and contrast of the theories (employing APA style), and (3) write a one-page reflection demonstrating each theory at work within popular media. Next, students exchanged their notes pieces, peer-reviewing each of the documents created by their three peers. Finally, they met face-to-face around a seminar table in the writing center for a discussion group where they reviewed the theories and APA style and citations. To help students with both content questions and writing-related questions, the TA for the course and the course-embedded tutor led small discussion groups.

The first part of the notes piece was intended to help student memorize elements of the theories that the accompanying exams would expect them to know. The second part was intended to deepen students’ contextual understanding of how multiple theories related to one another and to give them practice putting multiple sources into conversation with one another, which they would need to do in the final paper. The third part was intended to give students practice doing something the final paper required them to do: employ an example from the popular media to demonstrate and then interpret a particular criminological theory. Grouping students helped to (1) crowdsource the labor of covering exam content and to decrease the discreet number of assignments students completed, (2) increase student engagement with the work required of them outside of class, and (3) employ a peer-to-peer model that would help students help one another.

On Learning: Quantitative Writing Center Research

In closing, we want to echo Doug Enders’ insight gained from his foray into quantitative writing center research: “performing quantitative studies is difficult, but a few precautionary measures can help” (8). Emphasizing our positionality as learners, we want to share what we learned about conducting quantitative research in the writing center with others who might find it handy to be able to speak objectively and precisely, in the context of their own campuses and research portfolios, about what their WAC faculty partners can reasonably expect writing center impact to look like in students’ writing:

Pilot. Pilot the course-embedded model of instruction. Talk with your Center for Teaching and Learning colleagues and get feedback and advice about validated instruments that lie beyond writing studies journals. Pilot the instruments you eventually build to codify writing. Tweak the instruments and even your entire research protocol if necessary before you launch the full-scale study. A pilot will give you a good sense of what you have time and resources to accomplish, especially if this is your first quantitative writing research project. For instance, we thought we might also use a revision taxonomy on the two drafts of the longer research paper to identify revisions students made between drafts. We would then seek correlations between errors in papers one through four and revisions students made between the multi-draft assignment. This process would enable us to investigate an additional layer of transfer and to learn more about how the same students applied feedback across different drafts and multiple drafts of the same assignment. We discovered in the course of our work that this was not a realistic immediate goal. With the level of work required, it was only sensible in the context of a cross-institutional study, which would give the fruits of our labor any applicability beyond our own context and curiosity.

Simplify. Start with research questions that can be answered by looking for simple correlations between two variables. Identifying relationships between multiple variables embedded within multiple courses over multiple time points requires complex statistical modeling, the kind that lives in quantitative disciplines.

Obsessively Archive and Organize. Spend a significant amount of time crafting a data management plan. Librarians on most college and university campuses can help with this. Data collection, analysis, and documentation procedures and protocols need to be clearly articulated and documented. In planning projects, researcher team leaders should plan to spend a significant amount of time developing materials and training the research team, which may include learning to use new software packages, or at least learning how data must be reported in order to be read by a program such as STATA or SPSS.

Binge Code. We recommend that textual analysis (quantitative coding of student papers) follow Lunsford and Lunsford’s model. Research teams would be well-served by coding a large mass of papers in extended spurts (for example, all-day Saturday coding sessions). We coded in-between tutoring sessions, teaching, research obligations, and service requirements. This made data management difficult, and we were delayed in our statistical analyses because we had to spend a significant amount of time tracking down coded papers whose results never made it into the SPSS file.

Lastly, we recommend that writing centers and WAC faculty collaborate on both writing pedagogy and assessment/research. In this study, each of the researchers (teacher and TAs for the course, writing center administrators, composition instructors, and writing center tutors) benefitted in myriad ways from gaining an embodied understanding of the complexity of what goes into “good writing” in any particular course.

Notes

One paper was dropped from fall 2014 analyses because it was plagiarized and thus received a 0.

In supplemental analyses, we ran all models with negative binomial poisson regression. All substantive results were the same. Therefore, we present OLS regression results for ease of interpretation.

We conducted a series of supplemental analyses including negative binomial poisson regression and ordered logistic regression. In the ordered logistic regression models, we created three categories roughly divided in thirds, high, medium, and low theory engagement and comprehension. The results with these alternative models showed no substantive differences from OLS. Therefore, we present OLS regression results for ease of interpretation.

Works Cited

Babcock, Rebecca Day, and Terese Thonus. Researching the Writing Center: Towards Evidence-Based Practice. Peter Lang Inc., 2012.

Boquet, Elizabeth, and Neal Lerner. “Reconsiderations: After ‘The Idea of a Writing Center.’” College English, vol. 71, no. 2, 2008, pp. 170-189.

Brannon, Lil, and North, Steven. From the Editors. Writing Center Journal, vol. 1, no. 1, 1980, pp. 1-3.

Broad, Bob. “Strategies and Passions in Empirical Qualitative Research.” Writing Studies Research in Practice: Methods and Methodologies, edited by Lee Nickoson and Mary P. Sheridan-Rabideau, Southern Illinois UP, 2012, pp. 197-209.

Bromley, Pam, Kara Northway, and Eliana Schonberg. “Bridging the Qualitative/Quantitative Divide in Research and Practice.” Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, vol. 8, no. 1, 2010.

Cullick, Jonathan S. and Terry Myers Zawicki. Writing in the Disciplines: Advice and Models. Bedford/St. Martins, 2011.

Driscoll, Dana Lynn and Sherry Wynn Perdue. “Theory, Lore, and More: An Analysis of RAD Research in The Writing Center Journal, 1980–2009. The Writing Center Journal, vol. 32, no. 2, 2012, pp. 11-39. www.jstor.org/stable/43442391. Accessed 28 June 2018.

Enders, Doug. “Assessing the Writing Center: A Qualitative Tale of a Quantitative Study. Writing Lab Newsletter, vol. 29, no. 10, pp.6-9. wlnjournal.org/archives/v29/29.10.pdf. Accessed 28 June 2018.

Forsythe, Kiley. “Introduction to the Writing Center and Course-Embedded Tutoring.” 2015. PowerPoint Presentation. Mississippi State University. Starkville.

Gillam, Alice. “The Call to Research: Early Representations of Writing Center Research.” Writing Center Research: Extending the Conversation, edited by Paula Gillespie et al., Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc., 2002, pp. 3-21.

Harris, Muriel. “Preparing to Sit at the Head Table: Maintaining Writing Center Viability in the Twenty-First Century.” Writing Center Journal, vol. 20, no. 1, 2000, pp. 3- 21.

Haswell, Richard. “Quantitative Methods in Composition Studies: An Introduction to Their Functionality.” Writing Studies Research Practice: Methods and Methodologies, edited by Lee Nickoson and Mary P. Sheridan, Southern Illinois UP, 2012, pp. 185-196.

Keith, Shelley. “CRM 3603: Criminological Theory.” 2015. Syllabus. Mississippi State University. Starkville.

Lerner, Neal. "Choosing Beans Wisely." Writing Lab Newsletter, vol. 26, no. 1, 2001, pp.1-5. wlnjournal.org/archives/v26/26.1.pdf Accessed 26 June 2018.

Lunsford, Andrea A., and Karen J. Lunsford. “‘Mistakes Are a Fact of Life’: A National Comparative Study.” College Composition and Communication, vol. 59, no. 4, 2008, pp. 781-806.

National Council of Teachers of English. Professional Knowledge for the Teaching of Writing. NCTE. 2016. www2.ncte.org/statement/teaching-writing/. Accessed 28 June 26, 2018.

North, Steven. “The Idea of a Writing Center.” College English, vol. 46, no. 5, 1984, pp. 433-446.

North, Steven. “Writing Center Research: Testing Our Assumptions.” Writing Centers: Theory and Administration, edited by Gary Olsen, National Council of Teachers of English, 1984, pp. 24-35.

Pfeifer, Heather L., and Caroline W. Ferree. “Tired of ‘Reeding’ Bad Papers? Teaching Research and Writing Skills to Criminal Justice Students.” Journal of Criminal Justice Education, vol. 17, no. 1, 2006, pp. 121-142.

Pleasant, Scott, et al. “‘By Turns Pleased and Confounded’: A Report on One Writing Center's RAD Assessments.” The Writing Center Journal, vol. 35, no. 3, 2016, pp. 105–140.

Regaignon, Dara Rossman and Pamela Bromley. “What Difference to Writing Fellows Programs Make.” The WAC Journal, vol. 22, pp. 41-63, 2011. wac.colostate.edu/journal/vol22/regaignon.pdf. Accessed 28 June, 2018.

Rendleman, Eliot. “Writing Centers and Mandatory Visits,” WPA-CompPile Research Bibliographies, no. 22, 2013. CompPile. comppile.org/wpa/bibliographies/Bib22/Rendleman.pdf. Accessed 28 June 2018.

Appendix A: Figures and Tables

Figure 1. Comparison of Writing Center Support by Semester

Figure 2. Total Number of Participants and Papers Completed by Semester

Figure 3. Gender and Race of Participants by Semester

Figure 4. Content Taxonomy for Short Paper Two

Table 1. Mean Errors Per Page

Table 2. Ordinary Least Squares Regressions Predicting Grammar and Mechanical Errors

Table 3. Ordinary Lease Squares Regression Predicting Engagement with and Comprehension of Theory B

Table 4. Ordinary Least squares Regressions Predicting Students' Engagement with and Comprehension of Theory A (N=162)

Table 5. Ordinary Lease Squares Regression Predicting Engagement with and Comprehension of Theory B

Appendix B: Revised Short Paper Assignment and Course-Embedded Writing Support Model, Spring 2016

Exam Prep Discussion Groups and Mini Writing Assignments

In class we drew numbers to determine which group member and therefore theories you will focus on for this assignment.

Group Member 1: An Essay on Crimes and Punishments (chapt. 1) and the Criminal Man (chapt. 2)

Group Member 2: Theory of Differential Association (chapt. 10) and Social Learning Theory of Crime (chapt. 11)

Group Member 3: Social Structure and Anomie (chapt. 13) and General Strain Theory (chapt. 16

Group Member 4: Social Bond Theory (chapt. 18) and General Theory of Crime (chapt. 19)

Mini Writing Assignments (due before discussion groups)

Due: via email to your group members, course-embedded tutor and course teaching assistant 48 hours before your scheduled meeting.

Note: Both your notes and your two 1-page reflection papers should use evidence from the content chapters of your textbook (as opposed to your professor’s lectures and PowerPoints and the introductory chapters in your textbook).

1) Notes (typed) that outline the major components of your assigned theories (see attached sheet for more details). (3%)

2) A 1 page (typed) reflection comparing and contrasting the two theories (3%)

Questions you want to address in your reflective paper:

How are the theories similar?

What is the significance of these similarities?

How are the theories different?

What is the significance of these differences?

You might find the following sentence structures helpful (tip: pick up a copy of They Say, I Say):

Theory 1 [insert proper name] claims that ________; likewise Theory 2 [insert proper name] notes that ___________. This similarity highlights the importance of ______.

While Theory 1 contends that ___________, Theory 2 argues that ___________. This difference between the two theories shows that ___________.

3) A 1 page (typed) reflection identifying an example of the theories in popular culture (movie, TV show, media) (3%)

The point of this second short reflective writing task is to help you develop an understanding of the theories you are reading about by having you apply theories to examples from the media (TV show, movie, or the news media etc.). In this written response, you should fully explain the example that you are using from popular culture (summary). Then, the meat of the writing assignment, you need to explain how the example you’ve summarized relates to the theories you are covering for your discussion group. It might be a good idea to select a few (2-4) specific concepts from each theory and demonstrate how the pop culture example illustrates these concepts. You should do this twice, once for each theory you are reporting on.

Remember that while we have not discussed APA style and citations (yet) in this course, you should attempt to use APA style and citations to the best of your ability in your reflections (use https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/560/01/ and the APA cheat sheet distributed in class to help).

Discussion Groups

Discussion Group meetings will be held in the Writing Center. Each meeting is scheduled to last 60 minutes. After you complete your written assignments individually, you will need to send them, via email, to each of your group members as well as course-embedded tutor and course teaching assistant. Before coming to your discussion group: print, read, and annotate (or add notes in the margins that explain, question, or comment) on each of your classmates’ notes and reflections. You should come to the meeting prepared to discuss the theories as well as your group members’ ideas and writing.

The goal of this discussion group is to help you prepare for your midterm exam—so read your classmates’ work carefully. They will have taken detailed notes over the material that will help you as you prepare for the exam. Make sure that you come to your discussion meeting prepared to ask your classmates questions and provide specific feedback on both their writing and their understanding of particular theories.

Examples of strong annotations:

Good example showing an important part of the theory.

I’m not quite sure what you mean here—you’re losing me in the writing here because _.

I would like to know more about this example and how it relates to the theories.

This connects with information in chapter ____.

This information is a little unclear—I would like to discuss this idea during the meeting

Another way of saying this is _____.

Another good example is ______.